Later Years and Death

White wrote numerous poems and essays during his life; a collection of his essays came out in 1977. That same year, White's wife passed away. He was devastated by the loss.

On October 1, 1985, White died at his home in North Brooklin, Maine. He was 86 and, according to The New York Times, had been suffering from Alzheimer's disease. White was survived by his son, Joel, his stepchildren, Roger Angell and Nancy Stableford and numerous grandchildren and great-grandchildren.

BIOGRAPHY |

| E.B. WHITE |

E.B. White and his Greenwich Village

When people hear the name E.B. White, most immediately think of the much-adored children’s’ classics, Charlotte’s Web, Stuart Little, and Trumpet of the Swan. However, his work extended far beyond that genre, and his literary “hats” included essayist, novelist, humorist, and poet (although he described himself as a “non-poet who occasionally breaks into song”). Like so many literary giants, White made Greenwich Village his home, in his case during the 1920s, 30s, and 40s, when the Village was brimming with young artists, poets, novelists, and critics.

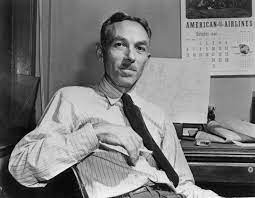

New York Times Co.

Elwyn Brooks White (July 11, 1899 — October 1, 1985) was born in Mount Vernon, New York, the youngest of six children. He graduated from Cornell University in 1921. He moved to New York in 1925 and took up residence with three of his Cornell fraternity brothers, renting an apartment at 112 West 13th Street. In E.B. White: A Biography by Scott Elledge, White is quoted as describing these years in Greenwich Village, particularly the summer of 1925 until the winter of 1926-27, as “lean and tortured,” a lonely period during which he endured “comparative unemployment,” working part-time for an advertising company. Nevertheless, he also considered this the “only genuinely creative period” of his life, as he had plenty of time to write and explore the city. Success began for the young writer when had several submissions to the then-new New Yorker magazine published, one of which, ‘Child’s Play,’ was particularly well received.

After a couple more successful submissions by White to the magazine, its literary editor, Katharine Angell recommended to editor-in-chief and founder Harold Ross that White be hired as a staff writer. White was reluctant at first to commit to a desk job, even as a writer. Eventually he consented, and became The New Yorker’s weekly contributing editor. White had a tremendous influence on the form, tone, and success of the burgeoning magazine, one of the most influential American literary magazines in the mid-20th century, and his contributions to the magazine would span nearly 60 years.

1929 was a busy year for White. He published a poetry collection, The Lady is Cold, and with fellow New Yorker magazine writer James Thurber co-authored a parody of books on Freudian psychology, Is Sex Necessary? White also married Katharine Angell in 1929, the editor at The New Yorker a who had recommended White for the staff writer position and a divorcee with two children. Following the wedding, White moved from his place on West Twelfth Street to her apartment 16 East 8th Street. Shortly after moving in, they increased their third floor, three-room space by renting the apartment directly above and installing an interior stairway between the two. In 1933 the Whites bought a farm in Maine which would serve them and their children as a second home.

By 1935, the Whites required more room than their six-room apartment on East 8th Street afforded, and moved to Turtle Bay Gardens, an artists enclave in the East 40s (White was however less than enthusiastic about leaving the Village). In 1944 the Whites came back to Greenwich Village to a furnished apartment on West 11th Street. Within a week of being back in his beloved Village, he wrote Village Revisited (A Cheerful lament in which truth, pain, and beauty are prominently mentioned, and in that order) writing:

Beauty recalled me. We bowed in the Square,

In the wonderfully westerly Waverly air.

She had a new do, I observed, to her hair.

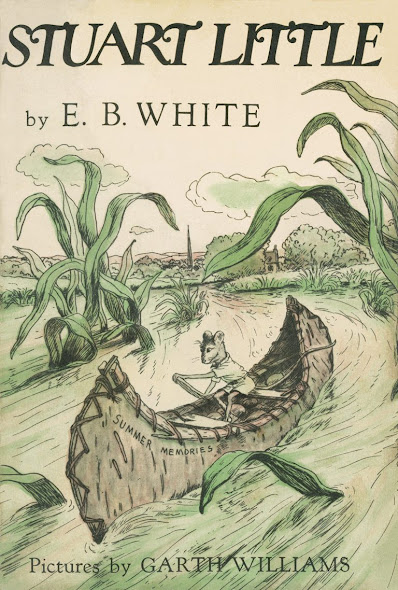

Within eight weeks of moving back to the Village, he completed the manuscript for Stuart Little (his first children’s book) which he had been working on for years. The book was published in 1945, and by the end of the following year, 105,000 copies had been printed (by 1977, 2.5 million copies had been sold). In 1946, the Whites moved back to Midtown, and eventually took up full-time residence at their farm in Maine.

In 1948, White wrote one of his most famous essays and best pieces on New York City, “Here is New York.” Originally written for Holiday Magazine, it was published in book version in 1949. He wrote it from the Algonquin Hotel during a summer visit to the city. If you haven’t read it or re-read it in a while, I recommend doing so. It offers its reader a window into post-World War II New York City; while some of the observations are very much of that time, some are timeless to New York City.

In 1952 White published Charlotte’s Web (published October 15th, 1952), placing him in the Pantheon of beloved children’s authors. In 1959 he along with his former Cornell professor William S. Strunk, Jr. collaborated on The Elements of Style, offering both rules of grammar and advice in writing style; this became a permanent fixture on College campuses for decades to come.

White received the National Medal for Literature in 1971, and two years later was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Letters. He was honored with the National Medal for Literature, a special Pulitzer award, and the Laura Ingalls Wilder Medal. White died of Alzheimer’s Disease in 1985 in Maine.

VILLAGE PRESERVATION |

| E.B. White |

Meet essayist E.B. White—and consider the advice he has to offer on writing and the writing process. Andy, as he was known to friends and family, spent the last 50 years of his life in an old white farmhouse overlooking the sea in North Brooklin, Maine. That's where he wrote most of his best-known essays, three children's books, and a best-selling style guide.

Introduction to E.B. White

A generation has grown up since E.B. White died in that farmhouse in 1985, and yet his sly, self-deprecating voice speaks more forcefully than ever. In recent years, Stuart Little has been turned into a franchise by Sony Pictures, and in 2006 a second film adaptation of Charlotte's Web was released. More significantly, White's novel about "some pig" and a spider who was "a true friend and a good writer" has sold more than 50 million copies over the past half-century.

Yet unlike the authors of most children's books, E.B. White is not a writer to be discarded once we slip out of childhood. The best of his casually eloquent essays—which first appeared in Harper's, The New Yorker, and The Atlantic in the 1930s, '40s, and '50s—have been reprinted in Essays of E.B. White (Harper Perennial, 1999). In "Death of a Pig," for instance, we can enjoy the adult version of the tale that was eventually shaped into Charlotte's Web. In "Once More to the Lake," White transformed the hoariest of essay topics—"How I Spent My Summer Vacation"—into a startling meditation on mortality.

For readers with ambitions to improve their own writing, White provided The Elements of Style (Penguin, 2005)—a lively revision of the modest guide first composed in 1918 by Cornell University professor William Strunk, Jr. It appears in our short list of essential Reference Works for Writers.

White was awarded the Gold Medal for Essays and Criticism of the American Academy of Arts and Letters, the Laura Ingalls Wilder Award, the National Medal for Literature, and the Presidential Medal of Freedom. In 1973 he was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Letters.

E.B. White's Advice to a Young Writer

What do you do when you're 17 years old, baffled by life, and certain only of your dream to become a professional writer? If you had been "Miss R" 35 years ago, you would have composed a letter to your favorite author, seeking his advice. And 35 years ago, you would have received this reply from E. B. White:

Dear Miss R:

At seventeen, the future is apt to seem formidable, even depressing. You should see the pages of my journal circa 1916.

You asked me about writing—how I did it. There is no trick to it. If you like to write and want to write, you write, no matter where you are or what else you are doing or whether anyone pays any heed. I must have written half a million words (mostly in my journal) before I had anything published, save for a couple of short items in St. Nicholas. If you want to write about feelings, about the end of summer, about growing, write about it. A great deal of writing is not "plotted"—most of my essays have no plot structure, they are a ramble in the woods, or a ramble in the basement of my mind. You ask, "Who cares?" Everybody cares. You say, "It's been written before." Everything has been written before.

I went to college but not direct from high school; there was an interval of six or eight months. Sometimes it works out well to take a short vacation from the academic world—I have a grandson who took a year off and got a job in Aspen, Colorado. After a year of skiing and working, he is now settled into Colby College as a freshman. But I can't advise you, or won't advise you, on any such decision. If you have a counselor at school, I'd seek the counselor's advice. In college (Cornell), I got on the daily newspaper and ended up as editor of it. It enabled me to do a lot of writing and gave me a good journalistic experience. You are right that a person's real duty in life is to save his dream, but don't worry about it and don't let them scare you. Henry Thoreau, who wrote Walden, said, "I learned this at least by my experiment: that if one advances confidently in the direction of his dreams, and endeavors to live the life which he has imagined, he will meet with a success unexpected in common hours." The sentence, after more than a hundred years, is still alive. So, advance confidently. And when you write something, send it (neatly typed) to a magazine or a publishing house. Not all magazines read unsolicited contributions, but some do. The New Yorker is always looking for new talent. Write a short piece for them, send it to The Editor. That's what I did forty-some years ago. Good luck.

Sincerely,

E. B. White

Whether you're a young writer like "Miss R" or an older one, White's counsel still holds. Advance confidently, and good luck.

E.B. White on a Writer's Responsibility

In an interview for The Paris Review in 1969, White was asked to express his "views about the writer's commitment to politics, international affairs." His response:

A writer should concern himself with whatever absorbs his fancy, stirs his heart, and unlimbers his typewriter. I feel no obligation to deal with politics. I do feel a responsibility to society because of going into print: a writer has the duty to be good, not lousy; true, not false; lively, not dull; accurate, not full of error. He should tend to lift people up, not lower them down. Writers do not merely reflect and interpret life, they inform and shape life.E.B. White on Writing for the Average Reader

In an essay titled "Calculating Machine," White wrote disparagingly about the "Reading-Ease Calculator," a device that presumed to measure the "readability" of an individual's writing style.

There is, of course, no such thing as reading ease of written matter. There is the ease with which matter can be read, but that is a condition of the reader, not of the matter.

There is no average reader, and to reach down toward this mythical character is to deny that each of us is on the way up, is ascending.

It is my belief that no writer can improve his work until he discards the dulcet notion that the reader is feebleminded, for writing is an act of faith, not of grammar. Ascent is at the heart of the matter. A country whose writers are following the calculating machine downstairs is not ascending—if you will pardon the expression—and a writer who questions the capacity of the person at the other end of the line is not a writer at all, merely a schemer. The movies long ago decided that a wider communication could be achieved by a deliberate descent to a lower level, and they walked proudly down until they reached the cellar. Now they are groping for the light switch, hoping to find the way out.

E.B. White on Writing With Style

In the final chapter of The Elements of Style (Allyn & Bacon, 1999), White presented 21 "suggestions and cautionary hints" to help writers develop an effective style. He prefaced those hints with this warning:

Young writers often suppose that style is a garnish for the meat of prose, a sauce by which a dull dish is made palatable. Style has no such separate entity; is nondetachable, unfilterable. The beginner should approach style warily, realizing that it is himself he is approaching, no other; and he should begin by turning resolutely away from all devices that are popularly believed to indicate style—all mannerisms, tricks, adornments. The approach to style is by way of plainness, simplicity, orderliness, sincerity.

Writing is, for most, laborious and slow. The mind travels faster than the pen; consequently, writing becomes a question of learning to make occasional wing shots, bringing down the bird of thought as it flashes by. A writer is a gunner, sometimes waiting in his blind for something to come in, sometimes roaming the countryside hoping to scare something up. Like other gunners, he must cultivate patience; he may have to work many covers to bring down one partridge.

You'll notice that while advocating a plain and simple style, White conveyed his thoughts through artful metaphors.

E.B. White on Grammar

Despite the prescriptive tone of The Elements of Style, White's own applications of grammar and syntax were primarily intuitive, as he once explained in The New Yorker:

Usage seems to us peculiarly a matter of ear. Everyone has his own prejudices, his own set of rules, his own list of horribles. The English language is always sticking a foot out to trip a man. Every week we get thrown, writing merrily along. English usage is sometimes more than mere taste, judgment, and education—sometimes it's sheer luck, like getting across a street.E.B. White on Not Writing

In a book review titled "Writers at Work," White described his own writing habits—or rather, his habit of putting off writing.

The thought of writing hangs over our mind like an ugly cloud, making us apprehensive and depressed, as before a summer storm, so that we begin the day by subsiding after breakfast, or by going away, often to seedy and inconclusive destinations: the nearest zoo, or a branch post office to buy a few stamped envelopes. Our professional life has been a long shameless exercise in avoidance. Our home is designed for the maximum of interruption, our office is the place where we never are. Yet the record is there. Not even lying down and closing the blinds stops us from writing; not even our family, and our preoccupation with same, stops us. |

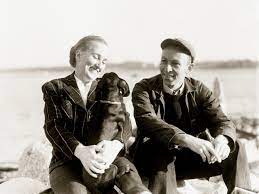

| One morning in Maine: Katharine and E. B. White (and Minnie) in the early fifties. |

Andy

By Roger Angell

Lately I have been missing my stepfather, Andy White, who keeps excusing himself while he steps out of the room to get something from his study or heads out the back kitchen door, on his way to the barn again. He’ll be right back. I can hear the sound of that gray door—the steps there lead down into the fragrant connecting woodshed—as the lift-latch clicks shut. E. B. White died in 1985—twenty years ago, come October—and by “missing” I don’t mean yearning for him so much as not being able to keep hold of him for a bit of conversation or even a tone of voice. In my mind, this is at his place in North Brooklin, Maine, and he’s almost still around. I see his plaid button-down shirt and tweed jacket, and his good evening moccasins. One hand is holding a cigarette tentatively—he’ll smoke it halfway down and then stub it out—and he turns in his chair to put his Martini back on the Swedish side table to his right. It must be about dinnertime. What were we talking about, just now? We were close for almost sixty years, and you’d think that a little back-and-forth—something more than a joke or part of an anecdote—would survive, but no. What’s impossible to write down, soon afterward, is a conversation that comes easily.

Andy makes light of the lost shoes in a tiny Notes and Comment piece he wrote for The New Yorker afterward, and I’ve remembered the day for boyish reasons—it was an adventure and it put me alone with someone I loved but didn’t see all that much. Actually, the story is right up his alley. In “One Man’s Meat,” the celebrated collection of his essays published in 1942, he recalls his dreamy seventeen-year-old self at home in Mount Vernon, New York, in 1917, just before he entered Cornell as a freshman. He was thinking of a girl he had skated with the winter before, when “the air grew still and the pond cracked and creaked under our skates,” and “the trails of ice led off into the woods, and the little fires burned along the shore. It was enough, that spring, to remember what a girl’s hand felt like, suddenly ungloved in winter.” The shift from the winter general to the sudden particular of the girl’s hand is a White special, as is the self-deprecation. And pegging along on a sidewalk in skates was an embarrassment that he would have made more of in a piece later on and played out with relish, as he did so often in his writings, turning the awkward moment into a charming and then telling paragraph, even as he dwells on his fears. He was the most charming man I’ve known, and he got that side of himself into his writing, like everything else, without effort.

Another winter scene is coming—this one a half century later—but first it should be explained that E. B. White was a lifelong hypochondriac, perhaps world class, but not a solemn one. Munching a canapé on my porch in Maine one evening, he clapped one hand to his face in horror. We paused, drinks in midair. “Got anything for cheese in the eye?” he cried indignantly. The crisis passed and the moment was affectionately filed away, joining the deadly ant bite at the beach picnic, the bone in his upper spine that was almost surely pushing its way through his windpipe, the passing ulcer or descending thrombus, and the thousand-odd spoonfuls of soup or compote, or forkfuls of salad or soufflé that were suddenly halted and inspected midway to his mouth, with the same “Any clams in this?” A clam had poisoned him once—though I don’t think I ever heard the meal or the mollusk named—and the cooks and hostesses of the world, including my mother, were out to lay him low again by the same means. No discussion followed a fresh alert. “Nope, no clams, Andy,” someone would murmur, and the meal resumed. If your eye fell on him later, you might notice that he was chewing, as always, with his mouth a quarter or an eighth open, ready to discharge any skulking bivalve that had slipped through the lines. Another quirk of his, almost as familiar as his gray mustache or his easeful walk, was a persistent leftward twist of his head, a little adjustment of neck and spine repeated every minute or so, retesting a structure on the verge of collapse.

I never had the feeling that Andy worked on his worries. He wasn’t exactly after attention, though that’s what he got at the spectacular upper levels of his discomposure. In the winter of 1980, word came to my wife, Carol, and me in New York that a cherished Maine neighbor of ours, Catherine McCoy, had died. There would be a memorial in Blue Hill, early in January, and after discussion we agreed that Carol would fly up to Bangor while I stayed home with our ten-year-old son, John Henry. My mother had died three years earlier, and Andy was delighted by the unexpected visitor, though it was understood that he would not attend the ceremony. Public gatherings—and most private ones, as well—made him jumpy. For years he had passed up family weddings and graduations, town meetings, dedications and book awards, cocktail bashes and boat gams and garden parties. As his literary reputation widened when he was in his forties and fifties, he did make it to a few select universities to receive honorary degrees, but despite prearranged infusions of sherry or Scotch he found the ceremonials excruciating. “So the old emptiness and dizziness and vapors seized hold of me,” he writes to my mother after his honoris causa Ph.D. appearance at Dartmouth in 1948. “Nobody who has never had my peculiar kind of disability can understand the sheer hell of such moments, but there they are.” And when the time came for the encomiums and the enrobing, there in the sunshine at Hanover, he went on, his hood—“white, quite big, and shaped like a loose-fitting horse collar”—became entangled with the honoree in the next seat, Ben Ames Williams: Andy’s worst dreams come true. “When I got seated the thing was up over my face, as in falconry,” he continues. “A fully masked Doctor of Letters, a headless poet.” After that, he stayed home, even passing up an invitation in 1963 to go to Washington and receive the Presidential Medal of Freedom from Lyndon Johnson; the deed was consummated instead by a stand-in, Maine’s Senator Edmund Muskie, in the office of the president of Colby College. Andy also skipped his wife’s private burial in the Brooklin Cemetery, in July, 1977. None of us in the family expected otherwise or held this against him. And when his own memorial came, eight years later, I took the chance to remark, “If Andy White could be with us today he would not be with us today.”

There would be no question of his accompanying Carol to Catherine McCoy’s farewell at the Blue Hill Congregational Church—except that a considerable snowstorm blew in overnight, converting the two-lane Route 175 to a slithery corridor the next morning. Carol said she’d drive herself over, but he wouldn’t hear of it; he’d drive her—he knew these winter roads. And so she found herself and the writhing public E.B.W. seated side by side near the front of the long church—the “Congo,” in local parlance—while preliminary organ music fell about them and the rows filled up with stomping, de-muffling mourners. When the music subsided and the footfalls of the minister were heard, Andy leaned toward Carol and whispered, “I’m having a heart attack.”

“I’m not leaving,” she whispered back, and kept her gaze straight ahead while he rose, excusing himself, and, half-bending but not unobserved, made his way out of the row and back up the aisle and, at last, through a door into the vestibule. The service and the tributes went on lengthily, at least for Carol. Had she done the right thing? She had no idea what she would find after the benediction and the recessional were over—certainly not the sight of Andy stretched on his back on one of the vestibule benches, a Saxon king atop his sarcophagus, as he responded to the anxious questions of each departing neighbor. “A heart attack,” he explained. “I had a heart attack.” In time, he arose, bundled up, and drove her safely back to North Brooklin for drinks and a nice dinner.

When the Whites moved to a year-round residency in Maine, in 1938, we kept in touch by letters, as everyone did in those days, but also, I began to realize, through his writings. He’d given up the Comment page he wrote each week for The New Yorker, and the eased deadlines and greater length of his monthly “One Man’s Meat” column in Harper’s suited the hours and bottomless concerns of a saltwater farmer with a hundred and fifty pullets, a dozen geese, twenty or thirty sheep, an editor wife (my mother had continued her work as a fiction and poetry editor with The New Yorker by long distance, with daily envelopes of galleys and proofs mailed back and forth between New York and Brooklin), a schoolboy son, Joel, and a full-time hired man. What he wrote about, along with the weather and the way to build a double-ended cedar scow for Joe and the way to keep a city rubber plant healthy with doses of “sheep-shit tea” (as it was known in the family, if not in print) and how to hook up a mooring with a chain so the tide will lift it free in the morning, was himself. The arrangement left room for his thoughts about the movies, automobile design, the railroads, taxation, domesticity, poetry, Florida trailer parks, and freedom. In 1937, a year before he began writing “One Man’s Meat,” Andy formally took a year off (“My Year” as he called it) to try—well, to try to become a serious writer. Nothing came of it, of course, but then the Harper’s assignment came along and saved his life. He was self-conscious at first as a countryman—he is abashed as he catches himself crossing the barnyard with a paper napkin in his hand—but the demands of the work and his affinity for it soon dismissed such concerns and somehow put him in place as a writer. The Whites, with their well-staffed household and sophisticated occupations, would always be “from away,” in Down East parlance, but no one in Brooklin who knew Andy ever took him for a gentleman farmer. When the war came, he even took on a cow—the first time he leads her out to the pasture, he writes, he feels “the way I did the first time I ever took a girl to the theatre”—and his production goals for 1942 were four thousand dozen eggs, ten pigs, and nine thousand pounds of milk.

I was away much of the time at boarding school and then at Harvard, and then elsewhere as a soldier, but the sense of home and informal but intimate attachment I got from Andy’s writings was even more powerful than it was for his other readers. Reading him brought him to me almost in person, as it still does in a 1955 passage about driving on U.S. 1, in Maine:

The moccasin joke survives—I think of it every year on the same stretch of highway, where the juniper and the foxes are scarcer now and the deer and the neon more prevalent. Reading the passage as a writer, I am struck by its simplicity and complexity, by that “punctually” and “barn attached” and the quick, sentence-closing “fox” and “cove.” What I feel for its author comes not just from my knowledge of him at the table or twitchy behind the wheel but from a sense of trust. He has looked at the roadside grunge and granite with the same eyes I do, and he does not labor for reference or add a chunk of scholarship to give them meaning; he waits for the connection—that extra moment—and delivers it with grace. I am included: this must be my thought, too, elegant as it has become. His editor William Shawn, writing after Andy’s death, called him the most companionable of writers, but added that “renowned as his writing was for its simplicity and its clarity, his mind constantly took surprising turns, and his peculiar mixture of seriousness and humor could not have failed to astonish even him.”

The other sentence-closer in the passage is “death,” and Andy must have ceased in time to be astonished at how often the theme and thought recurred in his writing. It runs all through his sweetly comical piece “Death of a Pig,” in which he tries ineffectually to deal with the crisis of a young pig of his who has stopped eating. Castor oil doesn’t help, nor does his own sense of “personal deterioration,” or the ministrations of Fred, who accompanies him on trips down the woodpath through the orchard to the pigyard, and also makes “many professional calls on his own.” The pig dies, nothing can be done about it, and it is the profusion of detail—his feeling the ears of the ailing pig “as you might put your hand on the forehead of a child,” and the “beautiful hole, five feet long, three feet wide, three feet deep” that is dug for the pig among alders and young hackmatacks, at the foot of an apple tree—that makes its death unsentimental and hard to bear.

The “d”-word also ends two famous essays of his, “Once More to the Lake” and “Here Is New York,” arriving without warning in the first one—a piece about taking his young son to a family summer camp where he himself often used to go as a kid. Everything there is the same, or almost—the middle lane, where the horse used to walk, has vanished from the road through the meadow—with the customarily spectacular afternoon thunderstorm thrown in. When it’s over and his boy is putting on his wet bathing suit for another dip, “I watched him, his hard little body, skinny and bare, saw him wince slightly as he pulled up around his vitals the small, soggy, icy garment. As he buckled the swollen belt suddenly my groin felt the chill of death.” I was a young man when I first read this, and remember finding the thought self-indulgent and exaggerated, almost a mistake, but this was before I’d begun to feel the brevity and sense of poignant loss that, from the first day, attend our meticulously renewed American vacations.

“Here Is New York,” written in 1948, was widely rediscovered in the weeks just after September 11th, because of its piercing vision. Reading the piece now—a revisiting of the pulsing and romantic city he knew and worked in during his late twenties and early thirties—you look for death at the end, since he has just mentioned that a small flight of planes could now bring down the great shining structure in a moment, but he almost appears to have given up on the idea. Has he forgotten the point? It arrives at the tail end of the last sentence, in the famously reversed final phrase: “this city, this mischievous and marvelous monument which not to look upon would be like death.” Losing New York is possible, but not holding on to the thought of it—which is all we may have in the end—much worse.

Andy White and my mother wove daily illness and incipient pain into their routines and conversations and their letters as they grew older. Her health was worse than his—she suffered from an exfoliating skin disease, went through a spinal-fusion operation and another dangerous procedure to clear a carotid artery, and endured painful bone deterioration in her old age, as a result of steroid treatments for the dermatosis—but if in the end she won their amazing sick-off, she took no pleasure in it and talked of his symptoms with the same concern and detail as her own. Their conversation became studded with lovingly enunciated medical reference: tachycardia, ileitis, the ethmoid sinuses. My older daughter, Callie, believes that what was most surprising about the Whites’ joint hypochondria was its energy; they were falling apart, they felt terrible, but they weren’t depressed. The narcissism and intimacy of their exchanged symptoms could be infuriating, since it excluded everyone else, but it was so dopey that you laughed at it and forgave them. When you turned up at their house after an absence, they’d ask you about your kids and your job and your recent doings, and almost in the same breath bring up a lingering migraine or this morning’s fresh back spasm. Someone in the family—someone who’d been reading about astronomy lately and remembered the “red shift” phenomenon as a measure of radiation and distance—named this the “White shift,” and it stuck.

All this, as I’ve said, showed itself late in their marriage, but a moment’s effort can bring back for me the way things were at home in better days, a couple of decades back—say on a late morning just after the mail has arrived. Their studies face each other across the narrow front hall, with the doors always open. My mother, in soft tweeds and a pale sweater, sits at her cherrywood desk, one leg tucked under her, with a lighted Benson & Hedges in one hand and a brown soft pencil in the other as she works her way down a page of Caslon-type galleys, with her tortoiseshell glasses down on her nose. Her desk is littered with papers and ashes and eraser rubbings. Across the hall, Andy sits up at his pine desk, facing her; a paste pot and a jar of pencils and some newspaper clips are arrayed before him, next to an old “in” basket, and a struggling winter sunlight touches the white organdy curtains by the north window. There are messages to himself taped up on the bookcase behind, near the worn stacks of the Encyclopedia, some bound volumes of The New Yorker, and a trusty Roget’s. The wallpaper here, curling a bit in the corners now, is made of connected blue-and-tan Coast and Geodetic Survey maps of Penobscot Bay, from the hills of Rockland in one corner, narrowing to a strip above the fireplace mantel, and all the way around to the waters near Mt. Desert Rock, in the other. Andy reads a passage aloud from today’s letter from Frank Sullivan or his brother Stanley or a grain merchant in Ellsworth, and my mother laughs, scarcely lifting her eyes from the page. Soon the noises of her typing out another letter to Harold Ross or Gus Lobrano are joined by the slower clatter of his Underwood: a New England light industry is again in full gear, pouring out its high-market daily product, and the labor force, for the moment, seems content. Soon it will be lunchtime.

To me, the Whites’ later concern with their health was a substitute joint effort, more loving than angry, and constituted a fresh form of intimacy as the two grew older. Andy missed the joy and youth that he had known in my mother and the passion that she had brought to her work as an editor, an obsessive gardener, and a non-stop letter-writer; once he told me how he mourned the day when she decided that she’d have to give up her evening Martini or Old-Fashioned. We in the family often speculated that Andy’s hypochondria wasn’t a way to stay close to her as much as fear of death in another form: if he could intercept each twinge and malaise as it arrived and bring it squirming to the light, then the ultimate event might yet be forestalled. But this is too easy. Rather, I’ve come to believe that his anxieties were a neurotic remnant of childhood. He was the last child of affectionate but older parents—his father, Samuel White, a piano-company executive, was forty-five when he was born and his mother, Jessie, forty-one. There were two prior brothers and three sisters; the oldest sibling, a sister named Marion, was eighteen years older than he was, and the youngest, Lillian, already a five-year-old. There seems to be no dark family event to seize upon, but one can imagine that a cough or a skinned knee or a passing stomach ache would have brought a rush of attention to young En (as he was called then) amid the daily news and doings of so many vibrant elders.

What is certain is the way that writing about death became a strength for him, and brought a lasting power in his best work. No one who feared death could have written the end of “Stuart Little,” in which the hero-mouse goes off in search of the heroine, a bird named Margalo, who has flown away “without saying anything to anybody.” But Stuart is also a romantic, like his creator, and interrupts his search for Margalo to invite a young girl he has met, Harriet Ames—she is just his size—to a picnic. He plans it carefully, but nothing goes right. The day is cloudy, Stuart has a headache, and some idle boys smash the souvenir birchbark canoe in which he means to take her for a paddle. He is disconsolate, and, when Harriet can’t cheer him up, she leaves.

The first sentence of “Stuart Little,” to be sure, is just as surprising as its shadowed endings—the fact that the Littles’ second child, on arrival, is a mouse, not a boy. White never explains the anomaly, and simply gets on with the story, but some critics and teacher-parent groups—and Anne Carroll Moore, the retired but still formidable children’s librarian at the New York Public Library—were collectively aghast. Harold Ross, who read everything, stuck his head into Andy’s office one afternoon and said, “God damn it, White, at least you could have had him adopted.” The author and his readers—kids and their read-aloud elders—stayed calm, however, and “Stuart Little” sold a hundred thousand copies in the first fifteen months after publication.

Andy was not mouselike, but in these pages he is ready for love, though rueful about the results. In life, he was intensely, almost manically, domestic but always ready to fall a little in love, without the plans or bother of a full affair. Pretty girls, with brains and laughter, entranced him. One of them, a New Yorker assistant named Maryan Fox, by a later coincidence became a sister-in-law of mine. He also admired Susy Waterman, the wife of a Maine neighbor, Stan Waterman, and felt that she would be the perfect narrator for the Pathways of Sound recording of “Charlotte’s Web”—an assignment he took on himself in the end. For a long time, there was a Steinway baby-grand piano tucked in a corner of Andy’s study in Maine, and I can still hear him playing and singing the verse of a lilting old song—did he perhaps write and compose it himself?

On another day, he contrived an epochal whine, murmuring to Carol that he always came in third in my mother’s heart: first there was The New Yorker, then me (me, Roger), and then, way down the line somewhere, himself. “Are you crazy!” she cried. “How can you say such a thing? You’re always first with her—there’s nobody else. Then the magazine and then all the rest of us. Everybody knows this.”

Death was a more reliable companion. There is not even a concealing metaphor by the time “Charlotte’s Web” comes along, in 1952, seven years after “Stuart”: a great short novel that begins with “Where’s Papa going with that ax?” and ends, or just about, when Charlotte, the spider, describes her coming death to the disbelieving young pig Wilbur, whom she has saved from that axe. Then comes the line—experienced teachers or reading-aloud parents check to make sure that the Kleenex is handy—“No one was with her when she died.”

Andy showed class, that pause again, in waiting to write “Charlotte’s Web” until he had the country stuff in it down by heart. He knew how geese sounded when they were upset, and on what day in the fall the squashes and pumpkins needed to be brought in and put on the barn floor—which is to say that he’d still be himself in writing about it, and would not put in a word that might patronize his audience. He must have known as the chapters emerged that this would be his masterpiece, but it would not occur to him to feel uneasy that his best book was for children. Money and celebrity were not much on his mind. When his old friend James Thurber died, he wrote that he’d known him “before blindness hit him, before fame hit him.” Andy also turned down a Book-of-the-Month Club offer for a later book, “The Second Tree from the Corner,” because he did not want to delay its publication until it suited the promotional plans of the B.O.M. He wrote an apology to his publisher, Cass Canfield, for the loss of the promised extra revenue, in which he said, “There are other things in life besides twenty thousand dollars—although not many.”

It’s my belief—I can’t prove it—that there are still readers and writers who feel a debt to E. B. White because of the sparkle and directness they found in a few lines or passages he wrote decades ago. Some of them, to be sure, were third graders who were encouraged by their teachers to write him in North Brooklin, asking whether Stuart ever found Margalo, or what became of Wilbur in the fullness of age: these letters came in by the bagful, and in time Andy had to turn over the task of replying to others. Readers also remember the power of his pieces on freedom and the Constitution—his 1947 “Party of One” letters to the New York Herald Tribune, for instance, which took the paper briskly to task when it supported the blacklisting of the Hollywood Ten and others who refused to answer questions about their loyalty or past political affiliations. The Trib didn’t back down, and wrote that members of “the party of one” were “nearly always as destructive as they have been valuable.” White’s reply, which pointed out that “a difference of opinion became suddenly a mark of infamy,” won a fan letter back from Supreme Court Justice Felix Frankfurter.

White’s gift to writers is clarity, which he demonstrates so easily in setting down the daily details of his farm chores: the need to pack the sides of his woodshed with sprucebrush against winter; counterweighting the cold-frame windows, for easier operation; the way the wind is ruffling the surface of the hens’ water fountain. Clarity is the message of “The Elements of Style,” the handbook he based on an early model written by Will Strunk, a professor of his at Cornell, which has helped more than ten million writers—the senior honors candidate, the rewriting lover, the overburdened historian—through the whichy thicket. “Write in a way that comes naturally,” it pleads. “Do not explain too much.” Write like White, in short, and his readers, finding him again and perhaps absorbing in the process something of that steely modesty, may sense as well the uses of patience in waiting to discover what kind of writer will turn up on their page, and finding contentment with that writer’s life.

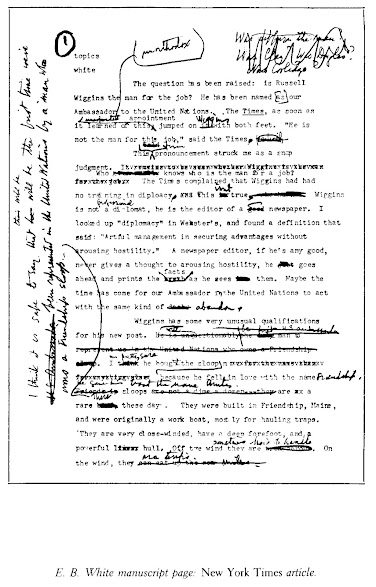

He was a demanding worker. He rewrote the first page of “Charlotte’s Web” eight times, and put the early manuscript away for several months, “to let the body heat out of it.” Then he wrote the book again, enlarging the role of the eight-year-old girl, Fern, at the center of its proceedings. He was the first writer I observed at work, back in my early teens. Each Tuesday morning, he disappeared into his study after breakfast to write his weekly Comment page for The New Yorker—a slow process, with many pauses between the brief thrashings of his Underwood. He was silent at lunch and quickly went back to his room to finish the piece before it went off to New York in the afternoon mailbag, left out in the box by the road. “It’s no good,” he often said morosely afterward. But when the new issue turned up the next week the piece was good—unstrained and joyful, a snap to read. Writing almost killed you, and the hard part was making it look easy.

What’s been left out of my account, of course, is most of a life: his son, Joel, and Joel’s wife, Allene, three grandchildren—all grown now, with kids and life stories of their own—and the Brooklin Boat Yard, where Joe built a career and earned a reputation as a master boat designer and builder that matched or continued his father’s as a writer. The Whites’ pasture isn’t here, sloping past the woodlot toward the shore, with the shapes of Herriman Point and then Mt. Desert coming clear beyond as the morning fog thins, nor is Fiddler Bayou, on Siesta Key, Florida, where the Whites passed so many winters. My mind, still in Maine, takes in the rubbly shore of Allen Cove, and the redolent boathouse, its surfaces softened with age, where we changed our clothes before swimming, and where Andy took himself, some days, to write or to work on his Newsbreaks selections for the magazine. Andy, getting ready to swim on a morning when the icy incoming tide has been warmed a fraction by its journey over mudflats, wades out until the water reaches his knees, then unfurls his old Abercrombie & Fitch thermometer and flings it out to the end of its twine tether. If the temperature is bearable—I think the red line stands at sixty-four degrees—he shakes his head and commits himself to the shallow deep.

Many in the family, including my children, have their own lasting and complex attachments to Andy and the Whites’ place. My daughter Alice, at about ten—an age when she’d read and been read “Charlotte’s Web” over and over again—was shocked to learn that a young pig in residence in an enclosure to the southwest of the garage would be converted to ham and bacon shortly after her departure in September. She worked late that evening, crayoning a large replica of Garth Williams’s “SOME PIG!” drawing in the book—the miracle web that saves Wilbur—and had me drive her back to the Whites’ that night, so she could secretly thumbtack it to the side of the pen. The agrarian Andy was startled but unmoved, and the pig went to his smoked reward on schedule.

Others in or around the Whites’ house are missing as well—Henry Allen, Edith Candage, Shirley Cousins, Tink Hutchinson, Howard Pervear. Andy’s lobsterman neighbor Charlie Henderson. Harold Ross—yes, Harold Ross, the magazine’s founder and editor—who probably never made it to the Whites’ place but who, right up until his death, in 1951, was so much a part of their daily thoughts and mealtime conversation that I sometimes almost saw him sitting at the table across from me, with his hunched shoulders and that gap in his teeth. Henry Lawson, Joe and Tooey Wearn, Russell Wiggins, Dottie Hayes. Fifty years of Brooklin friends and neighbors, who all knew or almost knew Andy, and respected his emphatic privacy. (When he was old, Brooklin townspeople would turn away pilgrim tourists who’d come all this distance to visit the shrine. “The E. B. White place? Well, it’s hard to say how you’d get there from here. Anyway, I don’t think he’s around right now.”) Sometimes, away for months on end, I felt in danger of falling out of touch, but then another letter from Andy would arrive, like this one from June 24, 1964: “I’m the father of two robins and this has kept me on the go lately. They were in a nest in a vine on the garage and had been deserted by their parents, and without really thinking what I was doing I casually dropped a couple of marinated worms into their throats as I walked by a week ago Monday. This did it. They took me on with open hearts and open mouths, and my schedule became extremely tight. I equipped myself with a 12" yellow bamboo stick, split at one end like a robin’s bill, and invented a formula: hamburg, chicken mash, kibbled worm, and orange juice. Worms are hard to come by because of the drought, but I dig early and late and pay my grandchildren a penny a worm. The birds are now fledged and are under the impression that they know how to fly. When I come out of the house at 6 a.m. they come streaming at me from bush and tree, trying for a landing on shoulder or cap, usually overshooting me in the fog and bringing up against a wall. This exhausts them and me.” (The stimulating “Letters of E. B. White,” out of print for some time, will reappear next year, in a new and updated printing, edited by his granddaughter Martha White.)

My mother died in 1977, and Andy stayed on alone in the house for the rest of his life. Well, not entirely alone. As he grew older, he began to spoil himself a little, and why not. Sometimes when he was having a bad spell with his head he would check himself into the Blue Hill Hospital for two or three days, until he felt better. He liked a meal out now and then, at the Blue Hill Inn, sometimes with company and just as often alone. He took drives in the afternoon with Ethel Howard, the wife of a Sedgwick garageman, whose conversation he enjoyed; and had occasional visits from Corona Machemer, a Harper & Row editor who had worked with him on late collections of his works. He gave up sailing the sturdy twenty-foot sloop Martha, named for the same granddaughter, which Joel had built and rigged for use by a cautious single-hander; he was a morning sailor by now, anyway. Andy worried what might befall him when he was alone, and paid a succession of nurse-companions to be in the next room if he woke up in the night and needed a morsel of talk or a glass of milk. Older women, quite a few of them, set their caps for him, of course, and were disappointed. He told Carol once that he didn’t plan to marry again. “I’m afraid I might get a lemon this time,” he said.

He was the same, still lithe and only a bit slower, and one evening in August, 1984, when he came for dinner he complained that he’d knocked his head the day before while unloading a canoe from the roof rack of his car, over at Walker Pond; now he was having trouble knowing exactly where he was or what was happening around him. Carol and I smiled at him. “Yes, that happens sometimes, doesn’t it?” we assured him.

But he knew better. A couple of months later, after we’d left, he took to his bed and never again knew exactly where he was. It looked like a rapid onset of Alzheimer’s, but more likely, the doctors thought, was a senile dementia brought on by the blow to his head that day. He was eighty-five now. Nurses and practical nurses and other local ladies were hired, round the clock, who took extraordinary care of him. My brother managed it all, and somehow managed his own life as well. When I came up for a visit, early in the winter, Joe said that Andy would know me but that our conversation would be interesting. “How do you mean?” I said. “You’ll see,” he said.

I walked in and found him restless in his bed and amazingly frail. His eyes lit up and he said my name in the old way: “Rog!” He wanted to know how I’d come from New York and I said that Henry Allen had picked me up at the Bangor airport. “Did you fly over Seattle on the way?” he asked. He didn’t seem troubled when I said no, and after a moment murmured, “Lost in the clouds.”

He died the next October, still at home and able to recognize the people around him. Joe told me that in that long year he’d read aloud to his father often, and discovered that he enjoyed listening to his own writings, though he wasn’t always clear about who the author was. Sometimes he’d raise a hand and impatiently wave a passage away: not good enough. Other evenings, he’d listen to the end, almost at rest, and then ask again who’d written these words.

“You did, Dad,” Joe said.

There was a pause, and Andy said, “Well, not bad.” ♦

%20(1).jpeg)

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario