|

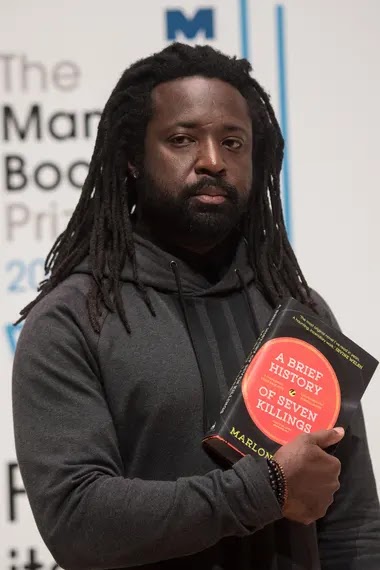

| Marlon James |

Marlon James

(1970)

Marlon James was born in Jamaica in 1970. His novel, A Brief History of Seven Killings, won the 2015 Man Booker Prize, making James the first Jamaican author to take home the U.K.’s most prestigious literary award. The novel also won the American Book award, the Anisfield-Wolf Book Award, and the Minnesota Book Award. It was a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award and was a New York Times Notable Book. Professor James is also the author of The Book of Night Women, which won the 2010 Dayton Literary Peace Prize and John Crow’s Devil. His next novel, Black Leopard, Red Wolf will be published in February 2019.

Professor James graduated from the University of the West Indies in 1991 with a degree in Language and Literature and from Wilkes University in 2006 with a Master’s Degree in creative writing. His short fiction and nonfiction have appeared in Esquire, Harpers, The New York Times, Granta, GQ, and the Caribbean Review of Books. At Macalester College James focuses on Contemporary Fiction, Narrative Nonfiction, and introductory poetry.

2022-2023 Academic Year

Professor James is on research leave for Fall 2022 and will return Spring 2023.

Fellowships and Honors

- Man Booker Prize (2015)

- Minnesota Book Award for Fiction (2010, 2015)

- Anisfield-Wolf Fiction Prize (2015)

- OCM Bocas Fiction Prize for Caribbean Literature (2015)

- Council For The Institute Of Jamaica Silver Musgrave Medal For Distinguished Eminence in the Field Of Literature (2013)

- Go On Girl Book Club Author Of The Year (2012)

- The Dayton Literary Peace Prize (2010)

- Finalist, National Book Critics Circle Award For Fiction (2009)

- Finalist, NAACP Image Award (2009)

- Finalist, Commonwealth Writers Prize (2006)

Publications

Fiction (Novel)

Black Leopard, Red Wolf Riverhead 2018

A Brief History of Seven Killings Riverhead 2014

The Book Of Night Women Riverhead 2009

John Crow’s Devil Akashic Books 2005

Fiction (Short Story)

“How To Be A Man” Esquire Magazine 2013

“Immaculate” (Kingston Noir) Akashic Books 2012

“Look What Love Is Doing To Me,”(Bronx Noir) Akashic Books 2007

“The Last Jamaican Lion,” (Iron Balloons: Hit

Fiction From Jamaica’s Calabash Workshop) Akashic Books 2006

Nonfiction

“Why I’m Done Talking About Diversity,” [Lit Hub, Fall 2016]

“Blacker the Berry —On Kendrick Lamar” [The New York Times Magazine

(March 2016)]

“From Jamaica, To Minnesota, to Myself” [The New York Times Magazine

(March 2015)]

“The Other Caribbean City” [New Orleans: What Can’t Be Lost: 88 Stories And

Traditions From The Sacred City] Lee Sophia Barclay, ed. The University of

Louisiana at Lafayette Press, (Fall 2010)]

“Growing Up With The King Of Pop,” [Granta. John Freeman, ed. (June 2009)]

“Jean Rhys’ Worthless Women,” [The Caribbean Review Of Books. Nicholas

Laughlin, ed. MEP Publishers (2008)]

“When You’re Not White Enough To Write a Black Novel.” [The Caribbean Review Of Books. Nicholas Laughlin, ed. MEP Publishers (2006)]

Reviews

The Island Beneath The Sea, by Isabelle Allende [Publisher’s Weekly. Jonathan Segura, ed. Reed Business (April 2010)]

Wonder Boy: Junot Diaz’s The Brief Wondrous Life Of Oscar Wao [The Caribbean

Review Of Books. Nicholas Laughlin, ed. MEP Publishers (2008)]

Words To Our Now: Imagination and Dissent, by Thomas Glave” [The

Caribbean Review Of Books. Nicholas Laughlin, ed. MEP Publishers (2006)]

MACALESTERAuthor of A Brief History of Seven Killings – a fictional account of an attempt to take Bob Marley’s life – first Jamaican writer to win prestigious prize

Marlon James has become the first Jamaican writer to win the Man Booker prize, taking the award for an epic, uncompromising novel not for the faint of heart. It brims with shocking gang violence, swearing, graphic sex, drug crime but also, said the judges, a lot of laughs.

A Brief History of Seven Killings, a fictional history of the attempted murder of Bob Marley in 1976, was “an extraordinary book”, said Michael Wood, the chair of judges. “[It was] very exciting, very violent, full of swearing. It was a book we didn’t actually have any difficulty deciding on – it was a unanimous decision, a little bit to our surprise.”

James, aged 44, who lives in Minneapolis, is the first Jamaican author to win the prize in the Man Booker’s 47-year history.

His novel has a lot of fans: it was described by the New York Times as: “like a Tarantino remake of the The Harder They Come, but with a soundtrack by Bob Marley and a script by Oliver Stone and William Faulkner … sweeping, mythic, over-the-top, colossal and dizzyingly complex.”

Accepting the award from Camilla, the Duchess of Cornwall, James said: “I just met Ben Okri [who won for The Famished Road in 1991] and it just reminded me of how much of my literary sensibilities were shaped by the Man Booker prize ... it suddenly increases your library by 13 books.”

He dedicated his win to his late father with who, he recalled, he used to have Shakespeare duels with as a boy. “Who can have the longest soliloquy ... just imagine a father and son in a Jamaican rum bar.”

James said he hoped his win would bring more attention to Caribbean writing but he admitted he had to leave Jamaica to write the book, it was “a novel of exile ... I needed that distance, I needed that sense of maybe there wouldn’t be consequences.” He said it was the riskiest novel he had written, in terms of subject and form and it was “affirming” winning the prize. “I would have been happy with two people liking it.”

In his Guardian review, the Jamaican poet Kei Miller praised the book’s ambition, writing that “[it] explores the aesthetics of cacophony and also the aesthetics of violence.”

A Brief History of Seven Killings might not be to all tastes; Wood recalled someone telling him that they liked to give the winners to their mother to read and James’s book might be a little difficult.

“My mother would not have got beyond the first few pages, because of the swearing,” he said. “Another reaction to people who say they don’t want to read this kind of thing is ‘it is very good for them to read it’.”

Ultimately, he said, James’ novel was “the most exciting book on the list.”

The book, published by independent publisher Oneworld, might be called a “Brief History” but it is anything but: it runs to 686 pages with an enormous dramatis personae of hoodlums, CIA and FBI agents, ghosts, beauty queens and Keith Richards’ drug dealer.

James himself has credited Charles Dickens as one of his key influences. He told an interviewer: “I still consider myself a Dickensian in as much as there aspects of storytelling I still believe in – plot, surprise, cliffhangers.”

This year’s shortlist was striking for the grimness of the subject matter and the toughness of the reads.

The bookmakers’ favourite had been US writer Hanya Yanigahara for A Little Life, a huge, draining novel which contained some of the most awful accounts of child abuse, cruelty and self-harm that most people are likely to ever read. (Not that it was not brilliant too.)

The other books were Tom McCarthy’s Satin Island; Sunjeev Sahota’s The Year of the Runaways; Chigozie Obioma’s The Fishermen; and Anne Tyler’s A Spool of Blue Thread.

Jonathan Ruppin, web editor of Foyles bookshops, said James’s book was: “Visceral and uncompromising … but it’s also an ingeniously structured feat of storytelling that draws the reader in with its eye-catching use of language.

“For booksellers, it’s truly heartening to see such ambition and originality recognised and rewarded, and readers have already been embracing it with great enthusiasm.”

James was handed his £50,000 prize at a black tie dinner at London’s Guildhall on Tuesday night. With the money will likely come a big rise in sales: last year’s winner, Richard Flanagan and The Narrow Road to the Deep North, sold 300,000 copies in the UK and 800,000 worldwide.

This is the second year the prize has been open to writers of any nationality writing in English, which means Americans are eligible.

Wood said that was a good thing, widening the range of what was being considered by the judges. “The sheer range of stuff we read was amazing … there is stuff going on I didn’t know was going on,” he said.

His fellow judges this year were author Frances Osborne, wife of the chancellor George; poet and novelist John Burnside; journalist Sam Leith; and critic and broadcaster Ellah Wakatama Allfrey.

Wood, professor emeritus of English and comparative literature at Princeton, said it had quickly dawned on all the judges that James had to be the winner and there was no need for a vote. Not that the other books were not worthy contenders: “The call was easy but the distance was small.”

A Brief History of Seven Killings won because it kept surprising the judges, said Wood. “There are many, many voices in the book and it just kept on coming, it kept on doing what it was doing.

“There is an excitement right from the beginning of this book,” he said. “A lot of it is very, very funny, a lot of it very human.”

People should not be daunted or put off by the subject matter, he said. “It is not an easy read, it is a big book with some tough stuff and a lot of swearing but it is not a difficult book to approach.”

A Brief History of Seven Killings by Marlon James (Oneworld Publications, £8.99).

- This article was amended on 15 October 2015 to correct the Duchess of Cornwall’s title.

|

| ‘The verbal and other violence surrounding homosexuality in A Brief History of Seven Killings is emblematic of the reality.’ Photograph: Felix Clay |

Why Marlon James had to get out of Jamaica to win the Booker prize

One of the most remarkable things about Marlon James’s A Brief History of Seven Killings is the way he has managed to achieve a blend of standard English and Jamaican patois – despite the fact that these languages are still major faultlines in his homeland, where they define perceptions (and the reality) of status and worth.

Patois, which began to be elevated from mere street language to a bona fide medium of artistic expression by the now-deceased folklorist Louise Bennett, is slowly being accepted as a means of literary discourse. The linguistic shame is retreating. There is a growing realisation that patois can’t be silenced if authentic characterisations of Jamaica and Jamaicans are to be achieved. James’s winning of the Booker prize goes a long way toward an official affirmation of the parity of creole with English, and burnishes its literary qualities – as vibrant, direct and digestible – even among readers who are unschooled in Jamaican language and culture.Perhaps the middle class, which is even more dismissive and loathsome of patois than the elites, will feel more liberated to embrace Jamaican expression, even when it’s time to cuss some “claat”.

There is a wider point too: James’s style and focus represent the realignment of the current generation away from a quest for identity in Britain in exchange for America and opportunity. At the same time, the book’s linguistic honesty and rhythm reveal James’s and other younger writers’ determination not to sacrifice identity in seeking to globalise narratives for the sake of book sales.

It is true that James relies on the convenient refrain of crime, violence, poverty and ghettos, a crutch leaned on by too many Jamaican artists in poetry, prose and song. A Brief History of Seven Killings is a macabre montage of blood and gore mixed with political intrigue. But he tells the story more compellingly, more poignantly. This bolder, rawer approach distinguishes the ambition of younger writers, which is to lay bare the soul of Kingston’s slums, warts and all.

A Brief History of Seven Killings also shows how Jamaican writers, especially those who have the shelter of America and its liberal moral atmosphere, can be truer to themselves on issues such as homosexuality. James, an openly gay man who attended Wolmer’s Boys, one of Kingston’s prestigious boys’ schools, explores homosexuality and homophobia directly – a departure from decades-old taboos that skirted such controversial issues. The verbal and other violence surrounding homosexuality is emblematic of the reality; James says he left Jamaica because he was fearful he could become a victim of rage against “battyboys” – Jamaican parlance for gay men.

But he is escaping other things too – poverty, and the fact that he would have had little hope of becoming a bestselling author if he had remained in Jamaica . James, who has an English degree from the University of the West Indies, is also reflective of the imbalance threatening academia in the northern Caribbean island. About three-quarters of the university population is female, and with a restriction on teaching positions in high schools and tertiary colleges, there are few incentives to read for an English degree – especially for men.

Furthermore, Jamaica’s two major bookstores, Sangster’s and Kingston Bookshop, are reorganising their business models to focus more on the sale of tablets and other electronics to cushion a recent fall in books purchased. Why? Partly because in a tight economy, Jamaicans are more interested in bread-and-butter issues and can’t spend spare change on literature – because there’s no spare change left; and also because of a government clampdown on ballooning school book lists, which were considered excessive and exploitative.

But there is hope. As the emerging writing class, which includes James and the Forward poetry prizewinner Kei Miller, turn the spotlight on Jamaican literature, there is a growing belief that Caribbean authors can push new boundaries and create narratives that effectively recast narrow, stilted notions of island life beyond beachscapes, thatch huts and weed-smoking Rastafarians.

The legacy left by the Jamaican literary greats Claude McKay, Roger Mais, Olive Senior, Lorna Goodison and Mervyn Morris is in good hands.

|

| ‘I wanted to go back to being a fantasy geek’ … Marlon James Photograph: Katherine Anne Rose/The Observer |

Marlon James reveals first details of African fantasy trilogy

The opening volume of the Dark Star fantasy trilogy is due in 2018 and will be his first book since his 2015 Booker winner A Brief History of Seven Killings

Danuta Kean

Wednesday 11 January 2017

Marlon James has revealed the first details of his forthcoming fantasy trilogy, expected to begin appearing next year. Inspired by a row over The Hobbit and the desire to “geek the hell out of something”, the Man Booker prize winner is steeping himself in ancient African mythology with a view to creating a detailed, Tolkienesque fictional world.

James said the first of the three novels in the Dark Star sequence – titled Black Leopard, Red Wolf – should appear in autumn 2018. The following novels will be called Moon Witch, Night Devil and The Boy and the Dark Star.

Speaking to Entertainment Weekly, the A Brief History of Seven Killings author said the books will draw on the rich heritage of African legend and language in the same way JRR Tolkien drew on Celtic and Norse mythology to create The Lord of the Rings.

“The very, very basic plot is [that] this slave trader hires a bunch of mercenaries to track down a kid who may have been kidnapped,” he told the US magazine in an interview. “But finding him takes nine years, and at the end of it, the kid is dead. And the whole novel is trying to figure out: ‘How did this happen?’”

Each book will take the form of an eyewitness testimony that counters the previous book until the truth is revealed in the final instalment, he added.

The row over The Hobbit concerned the lack of diversity in the cast of the film adaptation. “It made me realise that there was this huge universe of African history and mythology and crazy stories, these fantastic beasts and so on, that was just waiting there,” he said.

A self-confessed “sci-fi geek”, the trilogy is a departure from the Jamaican-born writer’s three previous books, historical novels that deal with the colonial legacy. His last novel A Brief History of Seven Killings, which scooped the 2015 Man Booker prize, follows the attempt to assassinate singer Bob Marley in 1976 and its aftermath, through the crack wars of New York in the 1980s and back to Jamaica in the 1990s.

“I just became really fascinated with real, old, epic storytelling,” he said of the decision to move genres. “There are African epics that we still talk about – some of which are as old as Beowulf. Others, like The Epic of Son-Jara and The Epic of Askia Muhammad, I’ve been researching for years. When I started to really dig in to it, the book almost started writing itself.”

James said he had wanted to write a historical novel. “I wanted to go back to being a fantasy geek. I don’t know who I told this, but I said, ‘I just want to geek the hell out of something’.”

The books are set in a fantasy world in an indeterminate period after the fall of the Roman empire, and will be set in ancient African kingdoms including Kush and Songhai.

James admitted he is enjoying creating a comprehensively imagined world. Though the 46-year old had “not yet” followed Tolkien’s lead by inventing a language, he was studying African languages with a view to doing so.

|

| Marlon James Photo by Mark Seliger |

A Lesson From Marlon James, Epic Storyteller

By Mike Vangel

Update, October 8, 2019: Marlon James’ novel Black Leopard, Red Wolf is one of five novels nominated for this year’s National Book Award in fiction.

Despite the eclectic paintings on the walls and the giant windows overlooking South Minneapolis and the Mississippi River beyond, Marlon James insists there’s nothing particularly inspiring about the place he calls home, even though it may seem like an artistic oasis from the outsider’s perspective. For one thing, he says, none of the creative magic happens here, anyway. For another, he’d probably object to applying the term “creative magic” to his work at all—having just published his fourth novel, he knows by now that good writing is the result of daily routine, not random acts of inspiration.

A dozen years ago, the idea of a fourth novel might have seemed fanciful. Overcoming now-legendary difficulty (to the tune of 70+ manuscript rejections), James published a promising debut, and joined Macalester’s English department in 2007 as a visiting professor. After that initial travail, his career trajectory has been nearly straight upward: he was promoted to a tenure-track professor before being named the college’s first writer in residence in 2016. He has taught and inspired hundreds of students through his courses, including Introduction to Creative Writing, American Literature, and advanced workshops that guide students through writing a novel in a semester. And, of course, he kept writing himself, publishing two more novels about his native Jamaica: The Book of Night Women, which won a Dayton Literary Peace Prize and a Minnesota Book Award, and A Brief History of Seven Killings, which won (among other things) the Man Booker Prize, perhaps the most prestigious award in all of English literature.

His latest novel—Black Leopard, Red Wolf—was listed among the most anticipated works of 2019 in publications ranging from book blogs to the New York Times. We recently visited James at home to ask him about the book, his thoughts on writing and teaching, and why he still believes in fiction.

The following interview has been edited and condensed.

Tell us about Black Leopard, Red Wolf.

The book is the first part of a trilogy called Dark Star, the significance of which I’m going to reveal way in the future. It’s one story: a slave trader hires seven mercenaries to find his child and they completely botch it. The child is dead and there are only three witnesses, and each novel is a different witness telling the story. They’re telling versions of the same story that don’t add up at all.

The trilogy plays a lot with African history and mythology. As much as I’m hugely inspired by European mythology and history, I really wanted to write something that has nothing to do with those traditions. One thing that’s different, for example, is what we associate with night: the witching hour, midnight, darkness is scary. These mythologies lead into troubling perceptions in the West that have spilled over into everything from race to how we look at evil.

None of that exists in African mythology. In African mythology, it’s high noon that’s the scariest time of day. Vampires have no problem killing you in the daylight. It’s like a Western—it’s high noon that’s deserted, it’s high noon when people don’t go out. Midnight, on the contrary, is called the noon of the ancestors. It’s when your great-grandmother shows up, and who wouldn’t want the great-grandmother to show up? She’s way cooler than your mother.

Why was telling three versions of the story important to you?

The first thing I got rid of was the idea that there’s one version that’s authentic. In African storytelling, a lot of storytelling is done by the trickster. It’s a very European thing to think that because I’m telling you a story, the story is true. A lot of ancient storytelling didn’t look for truth in that way. Even when I was growing up, a lot of the stories my parents and grandparents told me every day were the same story—they just changed the ending. I don’t go back to ask, “Well, which one of these is true?” They’re all true and they’re all false. That’s a more realistic idea about storytelling.

In this book, the reader is going to have to decide: who are you going to believe? What do you think is justice? I’m not going to decide for them. I’m just going to put out these three people who are telling the same story. Who do you trust?

Is that what you set out to write, or did it change over time?

None of my books end up the way I intended. The one thing that they all have in common is that I’ll have a pretty solid idea, and then a character shows up and completely wrecks it. In my second novel, there was this character who was supposed to be a cleaning woman in a bar. I wondered: “Well, what’s her story?” And that rabbit hole went on for 600 pages, and it became her novel. A Brief History of Seven Killings started as a crime novel set in New York and Chicago in 1985. The main character was a hit man who was born in Chicago who is probably the sloppiest hit man ever, and he’s having romance troubles. And somehow that novel became a story about the Bob Marley assassination, which begins in 1976.

For this novel, I started out trying to write a fantasy novel, and standard fantasy novels tend to be about the fall of a royal house: it usually starts at the top and filters down. But this novel just wasn’t happening that way. Even though I had two years of research, and I knew all the characters, it couldn’t happen until I flipped it—

so instead of starting in the throne room and ending up on the street, it started in the street and ended up in the throne room. And that worked.

Carlos Fuentes says there is no greater tragedy than a book ending exactly the way you planned it. And I think if that happens, maybe the writer’s having too firm a grip on the story.

You’ve called this book an “African Game of Thrones.” How did you make that jump fully into the fantasy world?

In the realities I write about, the distinction between real and surreal isn’t there. Even my last novel is still anchored by a ghost who knows he’s dead. I guess people call it magical realism, but nobody who practiced magical realism called it that. Gabriel García Márquez wasn’t writing magical realism—he was writing reality. A world where there is real-life corruption and political intrigue, and a world where there are dragons and fairies, can be the same world without anything special about that.

I grew up reading fantasy. I learned more from comics than I did from any literary novel. It wasn’t as dramatic a turn for me as it might seem. What was more dramatic for me was letting go of the very same kind of Eurocentric beliefs because that’s what I was raised on. One of the running gags in the new novel is this ridiculous idea of the magical child, the child who shall rise up to lead armies against the tyrant. In my book, people make fun of it. They say, “What sort of stupid magical child are you?” And the magical child in the novel ended up doing a lot of things that magical children aren’t supposed to do.

How do you relate to your characters?

You do develop a relationship with characters, particularly the villains. It’s pretty easy to fall for the heroes, but you have to love everybody when you’re writing a story. You have to love that villain into existence. When I’m done with a book, I do end up missing my characters quite a bit. I spend a lot of time with these people, and I get to know them in ways that nobody else knows. It’s not different from getting super-involved in a relationship that ends.

A huge part of writing is knowing when to say goodbye to a character and to resist writing more than you should. It’s almost like knowing when to leave a party or when to leave somebody’s house. You can wear out your welcome with a novel. I like novels that leave me imagining what happened 10 days after the story ended. They continue another life in your head—or maybe your fanfiction account. I love the idea of fanfiction: people who have fallen for characters and don’t want to let them go. That’s when you know you’ve written a good character.

Do you ever get stuck while writing—and if so, how do you get unstuck?

All of my writer’s blocks happen before I start a book. Figuring out what story to tell: that’s its own crisis that can take me two years. Figuring out who’s going to tell it? That’s another year. I’ll do tons of trial and error to figure out just whose story it is. When I’m actually writing, then I write pretty fast. I wrote this novel in 16 months. I wrote my second novel in 18 months, but it took me two years to get there. It’s still a three-year process to write a book.

People ask me about my process. My process is: having a really cool bunch of friends who will say random stuff, and somehow I end up with a novel. That’s why I don’t believe in the myth of the reclusive author. There’s no good reclusive author. You need people. Writing is a very solitary profession that can only happen in a community of people.

What happens in two years of research?

Well, lots of depression and paranoia, that’s what happens. I start every novel pretty much a wreck. Most of the time I have a character and a situation, but it’s usually research that gives me a storyline. A lot of times, I’d be researching something and think, “This novel is writing itself.”

I tell my students you don’t create stories, you find them. I go through dozens if not hundreds of pages of fiction that won’t go anywhere because it’s me again trying to figure out what to write—and there’s no other way to figure out what to write other than to write. It’s trying on ideas for size and seeing if they work.

What’s your writing routine like?

When I sit down with my laptop, I go to work. To me, writing is work: that’s part of my process, that it’s a job. I’m a big believer in that if you establish a routine, the muses show up. I love when people say they write when they’re inspired. I’m like, “Oh my God, I haven’t been inspired to write since the Carter administration. How does that work?” I’ve got to pay bills. I can’t wait on inspiration to write a novel. I’d never write anything.

It’s a vocation. It’s practice. Dancers, musicians, and actors know what I’m talking about—I don’t have to convince them. But writers will say things like, “I couldn’t write today because I didn’t feel inspired.” And I’m like, “That’s lovely.” It’s about doing the work—and knowing that inspiration or creativity will show up once they realize you’re serious.

Writing is something I still approach with fear. I’m terrified when I start anything. I reach every blank page thinking this is the story where it will all crash and burn. There’s a difference between fear and being afraid. Fear is super useful. There’s a part of your brain that springs to action when the stakes are high. You have to write like this is going to be your last book, that they’re coming to take your pencils if you don’t write. Even if you have to invent stakes, you have to believe it matters. You’d better bring your best game.

What do you like to read?

I approach reading two different ways. If I’m writing a book, I usually have a reading list, and that can be dozens of books: for style, for factual research, some I’m reading just because I want to be inspired or because they pave the way I want to go. If I’m writing, it’s very hard to read books for fun, so I have a huge stack now that I’m trying to get through before I start writing the next book.

When I’m not writing, then I can go back to reading books—I don’t want to say for pleasure, because all reading is a pleasure for me. I read pretty much everything: tons of crime fiction, loads of sci fi, comics, literary fiction (but not as much as the other genres). I’m always on a mission to recapture the feeling of the first time a book blew my mind.

As successful as you’ve been with writing lately, what keeps you teaching at Macalester?

It’s fun to teach. It’s even fun to watch students challenge stuff I’ve taught them, because I say, “Bear in mind that everything I’m telling you is still one person’s opinion.” I learn a lot from these students. It’s certainly helped me to become a better writer.

Outside of teaching, I’m surrounded by professional writers who already have a very narrow idea of what they’re here to do. At Macalester, I’m constantly surrounded by students who are still defining that, for whom the literary universe is wide open and almost every day is a day of discovering something. That’s really, really infectious. That’s really why I keep doing it. Seeing people unlock something that they probably never even knew they had, or seeing them become better writers in huge leaps is inspiring.

What do you want students to take away from your classes?

I hope they realize they can write their way out of anything, that they can confront issues and problems through writing, examine the complicated nature of the world through it. Hopefully I’m not just equipping them with tools for writing but some kind of tools for living, too.

I hope they learn that writing is a craft. It’s an art, yes, but it’s also a craft and a practice. I also really want them to learn that writing is fun. It should be like any art: it should be the most fun and the hardest work you’ve ever done. And if it’s not both of those things? Make it both of those things, or quit. (I’m not telling my students to be quitters, by the way.)

Why is fiction important?

We tell ourselves fantastical stories to process the world. It’s one of the things I think ancient and present-day African storytelling has known all along. That’s why we have dragons. That’s why we have monsters. Hell, that’s why we have Bigfoot. The myths are what tell us about ourselves. We always use these fantastical creatures and stories to talk about what’s right in front of us. Our minds want the leap, we want the fantasy. That brings us closer to reality than reality itself. That’s something that the ancient storytellers already knew, but we need reminding. Art is one way of seeing the world and dealing with the world—the only thing that can do both things at the same time. That’s why we need it. That’s why we need fiction.

%20(1).jpeg)

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario