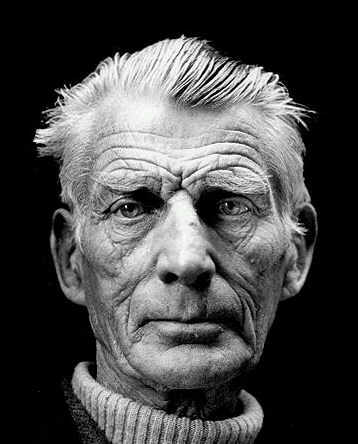

Samuel Beckett

(1906 - 1989)

Irish novelist and playwright, one of the great names of Absurd Theatre with Eugéne Ionesco, although recent study regards Beckett as postmodernist. His plays are concerned with human suffering and survival, and his characters are struggling with meaninglessness and the world of the Nothing. Beckett was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1969. In his writings for the theater Beckett showed influence of burlesque, vaudeville, the music hall, commedia dell'arte, and the silent-film style of such figures as Keaton and Chaplin.

"We all are born mad. Some remain so."

From Waiting for Godot, 1952

Samuel Beckett was born in Dublin into a prosperous Protestant family. His father, William Beckett Jr., was a surveyor. Beckett's mother, Mary Roe, had worked as a nurse before marriage. He was educated at the Portora Royal School and Trinity College, Dublin, where he took a B.A. degree in 1927, having specialized in French and Italian. Beckett worked as a teacher in Belfast and lecturer in English at the École Normale Supérieure in Paris. During this time he became a friend of James Joyce, taking dictation and copying down parts of what would eventually become Finnegans Wake (1939). He also translated a fragment of the book into French under Joyce's supervision.

In 1931 Beckett returned to Dublin and received his M.A. in 1931. He taught French at Trinity College until 1932, when he resigned to devote his time entirely to writing. After his father died, Beckett received an annuity that enabled him to settle in London, where he underwent psychoanalysis (1935-36).

As a poet Beckett made his debut in 1930 with Whoroscope, a ninety-eight-line poem accompanied by seventeen footnotes. In this dramatic monologue, the protagonist, Rene Descartes, waits for his morning omelet of well-aged eggs, while meditating on the obscurity of theological mysteries, the passage of time, and the approach of death. It was followed with a collection of essays, Proust (1931), and novelMore Pricks Than Kicks (1934). From 1933 to 1936 he lived in London.

In 1938 Beckett was hospitalized from a stab would he had received from a pimp to whom he had refused to give money. Around this time he met Suzanne Dechevaux-Dumesnil, a piano student, whom he married in 1961. When Beckett won the Nobel Prize, Suzanne commented: "This is a catastrophe." Beckett refused to attend the Nobel ceremony.

Beckett's career as a novelist really began with Murphy (1938), which depicted the protagonist's inner struggle between his desires for his prostitute-mistress and for total escape into the darkness of mind. The conflict is resolved when he is atomized by a gas explosion.

When World War II broke out, Beckett was in Ireland, but he hastened to Paris and joined a Resistance network. Sought by the Nazis, he fled with Dechevaux-Dumesnil to Southern France, where they remained in hiding in the village of Roussillon two and half years. Beckett worked as country laborer and wrote Watt, his second novel, which was published in 1953 and was the last of his novels written originally in English. It portrayed the futile search of Watt (What) for understanding in the household Mr. Knott (Not), who continually changes shapes.

After the war Beckett worked briefly with the Irish Red Cross in St. Lo in Normandy. Between 1946 and 1949 he produced the major prose narrative trilogy, Molloy, Malone Meurt, and L'innommable, which came out in the early 1950s. The novels were written in French and subsequently translated into English with substantial changes. Beckett said that when he wrote in French it was easier to write "without style" – he did not try to be elegant. With the change of language Beckett escaped from everything with which he was familiar. These books reflected Beckett's bitter realization that there is no escape from illusions and from the Cartesian compulsion to think, to try to solve insoluble mysteries. Beckett was obsessed by a desire to create what he called "a literature of the unword." He waged a lifelong war on words, trying to yield the silence that underlines them.

WINNIE: Win! (Pause.) Oh this is a happy day, this will have been another happy day! (Pause.) After all. (Pause.) So far.(from Happy Days, 1961)

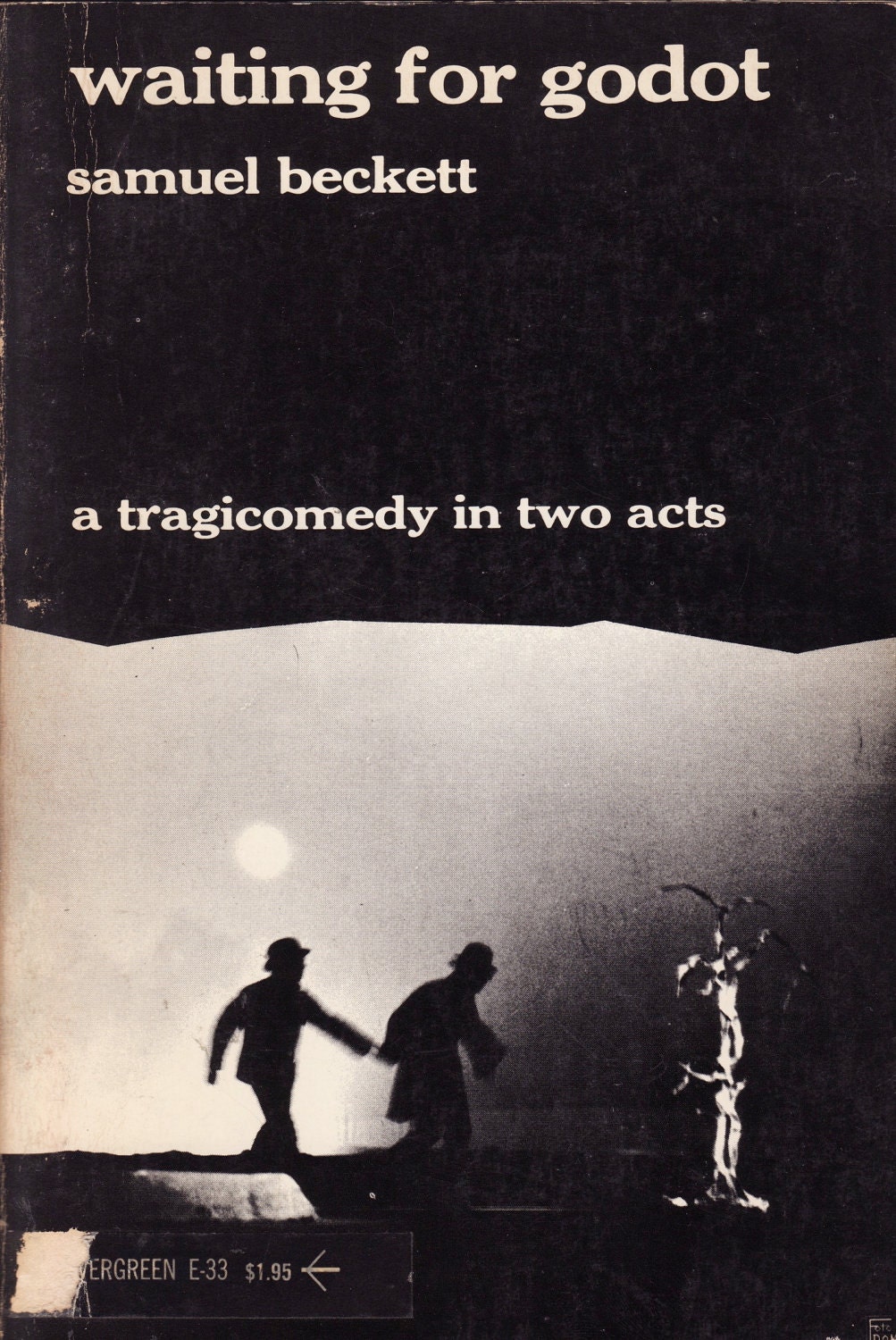

En attendant Godot (Waiting for Godot), written in 1949 and published in English in 1954, brought Beckett international fame and established him as one of the leading names of the theater of the absurd. Beckett more or less admitted in a New York Post interview by Jerry Tallmer that the dialogue was based on conversations between Suzanne Deschevaux-Dumesnil and himself in Roussillon. The tragi-comedy in two acts, opened at the Théâtre de Babylone on January 5, 1953, and made history. Two tramps, Vladimir and Estragon, who call each other Gogo and Didi, meet near a bare tree on a country road. They wait for the promised arrival of Godot, whose name could refer to 'God' or also the French name for Charlie Chaplin, 'Charlot'. To fill the boredom they try to recall their past, tell jokes, eat, and speculate about Godot. Pozzo, a bourgeois tyrant, and Lucky, his servant, appear briefly. Pozzo about Lucky: "He can't think without his hat." Godot sends word that he will not come that day but will surely come the next. In Act II Vladimir and and Estragon still wait, and Godot sends a promising message. The two men try to hang themselves and then declare their intention of leaving, but they have no energy to move. In Beckett's philosophical show, there is no meaning without being. The very existence of Vladimir and Estragon is in doubt. Without Godot, their world do not have purpose, but suicide is not the solution to their existential dilemma.

VLADIMIR: We have to come back tomorrow.

ESTRAGO; What for?

VLADIMIR: To wait for Godot.

ESTRAGON: Ah! (Silence.) He didn't come?

VLADIMIR: No.

After Waiting for Godot Beckett wrote Fin de partie (1957, Endgame) and a series of stage plays and brief pieces for the radio.Endgame developed further one of Beckett's central themes, men in mutual dependence (Hamm and Clov occupy a room with Nagg and Nell who are in dustbins). "One day you'll be blind, like me", says Hamm. "You'll be sitting there, a speck in the void, in the dark, for ever, like me." In Krapp's Last Tape (1959) Beckett returned to his native language. The play depicted an old man sitting alone in his room. At night he listens to tape recordings from various periods of his past.

In several works Beckett used dark humor to establish distance to his grim subjects. In his last full-length novel, Comment c'est (1961, How It Is) the protagonist crawls across the mud dragging a sack of canned food behind him. He overtakes another crawler who he tortures into speech and is left alone waiting to be overtaken himself by another crawler who will torture him in turn.

In the 1960s Beckett wrote for radio, theater, and television. During this decade, Billie Whitelaw became one of the most noted interpreter of Beckett's works. Her performances include Play, Not I, and Footfalls. She also acted in such films as Frency (written by Anthony Shaffer, dir. by Alfred Hitchcock, 1972), The Omen (1976), The Water Babies (1979), Maurice (based on E. M. Forster's posthumously published novel, dir. by James Ivory, 1987), and The Krays (1990). Alan Schneider staged most of the American premiers of Beckett's plays. Schneider also directed the short Beckett movie Film, starring Buster Keaton.

In the 1970s appeared Mirlitonnades (1978), a collection of short poems, Company (1979) and All Strange Away (1979), which was performed in 1984 in New York. Catastrophe (1984) was written for Vaclav Havel and was about the interrogation of a dissident. In 1988, Waiting for Godot, was produced at Lincoln Center. Steve Martin, Robin Williams, and Bill Irwin played in the central roles.

Beckett lived on the rue St. Jacques. At the neighborhood cafe he met his friends, drank espresso, and smoke thin cigarettes. He also had a country house outside Paris. Beckett maintained his usual silence even when his eightienth birthday was celebrated in Paris and New York. At the age of seventy-six he said: "With diminished concentration, loss of memory, obscured intelligence... the more chance there is for saying something closest to what one really is. Even though everything seems inexpressible, there remains the need to express. A child need to make a sand castle even though it makes no sense. In old age, with only a few grains of sand, one has the greatest possibility." (fromPlaywrights at Work, ed. by George Plimpton, 2000)

Beckett's wife died in 1989. The author had moved just previously to a small nursing home, after falling in his apartment. Beckett lived in a barely furnished room, receiving visitors, writing until the end. From his television he watched tennis and soccer. His last book printed in his lifetime was Stirring Still (1989). Beckett died, following respiratory problems, in a hospital on December 22, 1989. It it rumored that Beckett gave much of the Nobel prize money to needy artists.

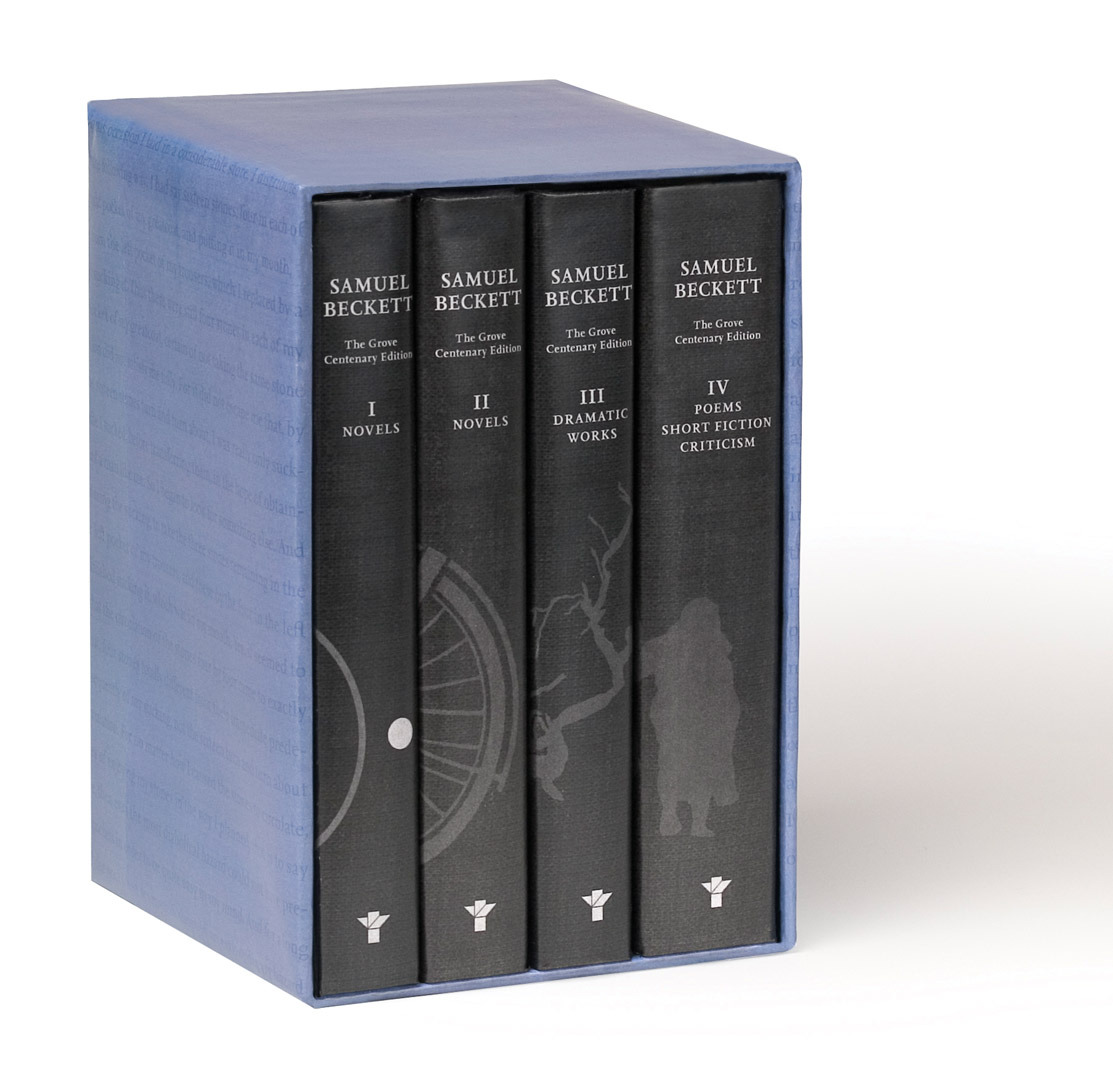

For further reading: Samuel Beckett: The Comic Gamut by Ruby Cohn (1962); Samuel Beckett by R. Hayman (1968); Samuel Beckett by J. Friedman (1970); Beckett by A. Alvarez (1973); Samuel Beckett: A Critical Study by Hugh Kenner (1974); Samuel Beckett: A Biography by Deirdre Bair (1978); Samuel Beckett by Linda Ben-Zvi (1986); The Beckett Actor: Jack Macgowran, Beginning to End by Jordan R. Young (1988); Waiting for Godot and Endgame - Samuel Beckett, ed. by Steven Connor (1992); Beckett's Dying Words by Christopher Ricks (1993); The Beckett Country by Eoin O'Brien (1994); Beyond Minimalism by Enoch Brater (1995); Beckett Writing Beckett by H. Porter Abbott (1996);Conversations With and About Beckett, ed. by Mel Gussow (1996); Damned to Fame by James Knowlson (1996); Samuel Beckett by Anthony Cronin (1997); Beckett and the Mythology of Psychoanalysis by Phil Baker (1998); The Grove Companion to Samuel Beckett: A Reader's Guide to His Works, Life, and Thought by C. J. Ackerly and S. E. Gontarski (2004) - See also: Alfred Jarry. Television adaptations: Beckett on film (2000), prod. by RTE and Gate theatre, directors include Conor PcPherson, Neil Jordan, David Mamet, Atom Egoyan, Richard Eyre, Karel Reisz, Anthony Minghella et al.

Selected works:

- Our Exagmination Round His Factification for Incamination of Work in Progress, 1929

- Whoroscope, 1930

- Proust, 1931

- More Pricks Than Kicks, 1934

- Echo's Bones and Other Precipitates, 1935

- Murphy, 1938

- Nouvelles et Textes pour rien, 1945-50 (written; L'Expulsé, Le Calmant, La Fin et Textes pour rien I-XIII)- Stories and Textes for Nothing (translation in 1955; The Expelled, The Calmative, The End, and Texts for Nothing I-XIII)

- Premier amour, 1946 (written)

- Eleuthéria, 1947 (written)- Eleuthéria: A Play in Three Acts, 1995 (translated from the French by Michael Brodsky)

- Molloy, 1951- Molloy: A Novel (translated from the French by Patrick Bowles in collaboration with the author, 1955)- Molloy (suom. Raili Phan-Chan-The, 1968)

- Three Dialogues, 1949 (with Georges Duthuit and Jacques Putnam)

- Malone meurt, 1951- Malone Dies (translated by the author, 1956)- Malone kuolee (suom. Caj Westerberg, 2007)

- L'innommable, 1953- The Unnamable (translated by the author, 1958)

- En attendant Godot, 1952 (written in 1948)- Waiting for Godot (translated by the author)- Huomenna hän tulee (suom. Aili Palmén, 1964; Antti Halonen ja Kristiina Lyytinen, 1990) / Godota odottaessa (suom. Arto Af Hällström, 2011)

- Watt, 1953- Watt (suom. Caj Westerberg, 2006)

- Fin de partie; suivi de, Acte sans paroles, 1957- Endgame (translated by the author, 1958)

- From an Abandoned Work, 1958

- L'image, 1958- The Image (translation in 1988)

- Bram van Velde, 1958 (by Jacques Putman, Georges Duthuit and Samuel Beckett)- Bram van Velde (translated from the French by Olive Classe and Samuel Beckett, 1960)- Sanaton näytös I & II (suom. Olli-Matti Ronimus, Pentti Holappa, 1964)

- Krapp's Last Tape, 1959

- All That Fall, 1959- Kaikkien kaatuvien tie (suom. Ville Repo, 1957)

- Acte sans paroles II, 1961

- Happy Days: A Play in Two Acts, 1961- Onnelliset päivät (suom. Olli-Matti Ronimus, Pentti Holappa, 1965) / Voi miten ihana päivä (suom. Juha Mannerkorpi, 1967)

- Rough for Radio I, 1961

- Rough for Radio II, 1961

- Comment c'est, 1961- How It Is (translated by the author, 1964)

- Collected Poems in English, 1961

- Words and Music, 1962

- Selected Poems, 1963 (translations by Samuel Beckett and others)

- Cascando, 1963

- Play, and Two Short Pieces for Radio, 1964

- Bing, 1965- Ping (translation in 1966)

- Imagination morte imaginez, 1965- Imagination Dead Imagine (London, Calder & Boyars, 1966)

- Assez, 1966- Enough (translation in 1974)

- Eh Joe, 1966 (television play)

- Come and Go, 1966- Va et vient (translated by the author, in Comedie et actes divers, 1966)

- Film, 1967

- A Samuel Beckett Reader, 1967 (edited by John Calder)

- No's Knife: Collected Shorter Prose, 1945-1966, 1967

- Eh Joe, and Other Writings, 1967

- L'Issue, 1968

- Sans, 1969- Lessness (translated by the author, 1968)

- Film. Complete Scenario, Illustrations, Production Shots, 1969 (with an essay on directing Film by Alan Schneider)

- Le Dépeupleur, 1970- The Lost Ones (translated by the author, 1971)

- Breath, 1970

- Premier amout, 1970- First Love (published by Calder and Boyars, 1973)

- Séjour, 1970 (illustrated with etchings by Louis Maccard after drawings by Jean Deyrolle)

- Mercier et Camier, 1970- Mercier and Camies (translated by the author, 1974)

- Breath and Other Shorts, 1971

- Abandonné, 1972 (illustrated by Geneviève Asse)

- The North, 1972 (with three original etchings by Avigdor Arikha)

- Not I, 1973

- La falaise, 1975- The Cliff (translation in 1991)

- All Strange Away, 1976 (illustrated by Edward Gorey)

- Ghost Trio, 1976

- That Time, 1976

- Rough for Theatre I, 1976

- Pour finir encore et autres foirades, 1976- Fizzles 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 , 6 (translated by the author, 1976)

- For to End Yet Again and Other Fizzles, 1976

- Four Novellas, 1977 (translated by the author and Richard Seaver)

- ... But the Clouds..., 1977

- Collected Poems in English and French, 1977

- Poèmes; [Mirlitonnades], 1978

- Company, 1979

- A Piece of Monologue, 1980

- Ohio Impromptu, 1981

- Nohow, 1981

- Mal vu mal dit, 1981

- Rockaby and Other Short Pieces, 1982

- Catastrophe et autres dramaticules, 1982

- A Piece of Monologue, 1982

- Worstward Ho, 1983

- What Where, 1983

- Nacht und Träume, 1983

- Disjecta: Miscellaneous Writings and a Dramatic Fragment, 1983 (edited with a foreword by Ruby Cohn)

- Collected Shorter Plays, 1984

- Quad, 1984 (television play)

- Human Wishes, 1984 (written c.1936)

- The Complete Dramatic Works, 1986

- Hommage à Jack B. Yeats, 1988

- Teleplays, 1988

- Le monde et le pantalon, 1989

- Stirring Still, 1989

- What is the Word, 1989

- As the Story was Told: Uncollected and Lat Prose, 1990

- Dream of Fair to Middling Women, 1992 (edited by Eoin O’Brien and Edith Fournier; foreword by Eoin O’Brien)

- The Complete Short Prose 1929–1989, 1929-1989, 1995 (edited by S. E. Gontarski)

- Nohow On: Three Novels, 1996 (with an introduction by S.E. Gontarski)

- No Author Better Served: The Correspondence of Samuel Beckett & Alan Schneider, 1998 (edited by Maurice Harmon)

- The Letters of Samuel Beckett. Volume: 1 1929–1940, 2009 (ed. by Martha Dow Fehsenfeld and Lois More Overbeck)

- Selected Poems 1930–1989, 2009 (edited by David Wheatley)

- The Letters of Samuel Beckett. Volume: 2 1941–1956. Samuel Beckett, 2011 (eds. Martha Dow Fehsenfeld, Lois More Overbeck, Dan Gunn & George Craig)

- The Collected Poems of Samuel Beckett, 2012 (edited by Seán Lawlor and John Pilling)