|

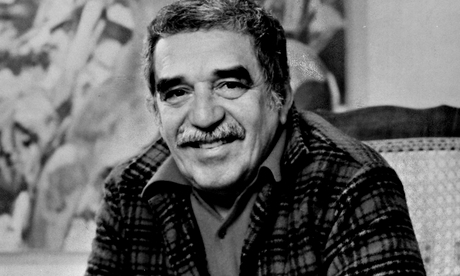

| Gabriel García Márquez |

OPEN LINES / ONE HUNDRED YEARS OF SOLITUDINE

OPEN LINES / THE AUTUMN OF THE PATRIARCH

GARCÍA MÁRQUEZ / THE AUTUMN OF THE PATRIARCH

THE ART OF FICTION

GEORGES SIMENON

GARCÍA MÁRQUEZ BY GERALD MARTIN

GARCÍA MÁRQUEZ / A LIFE / EXCERPET

BROTHER SAYS GARCÍA MÁRQUEZ HAS DEMENTIA

GARCÍA MÁRQUEZ / LOVE AND CARTAGENA

GABRIEL GARCÍA MÁRQUEZ MEETS ERNEST HEMINGWAY

GARCÍA MÁRQUEZ / SOLITUDE AND NOBEL

MARLESE SIMONS / A TALK WITH GABRIEL GARCÍA MÁRQUEZ

STORYTELLER WITH BENT FOR REVOLUTION

NATALIA DEPRINA / EVA IS INSIDE HER CAT

QUOTE

WHY VARGAS LLOSA TRUMPED GARCÍA MÁRQUEZ

JON LEE ANDERSON / THE POWER OF GABRIEL GARCÍA MÁRQUEZ

GARCÍA MÁRQUEZ / MEMORIES OF MY MELANCHOLY WHORES / REVIEW BY JOHN UPDIKE

GARCÍA MÁRQUEZ / THE BEST YEARS OF HIS LIFE / AN INTERVIEW

LOVE AND AGE / A TALK WITH GARCÍA MÁRQUEZ

GARCÍA MÁRQUEZ / SHORT FORM

GARCÍA MÁRQUEZ / STRANGE PILGRIMS / REVIEW BY WILLIAM BOYD

GARCÍA MÁRQUEZ / IN THE SHADOW OF THE PATRIARCH

GARCÍA MÁRQUEZ / ONE HUNDRED YEARS OF SOLITUDE / DAVID GALLAGHER/

DAVID WHITE / GARCÍA MÁRQUEZ MADE THE TECHNIQUE HIS OWN

GARCÍA MÁRQUEZ DIES AGED 87

GARCÍA MÁRQUEZ / A LIFE IN PICTURES

GARCÍA MÁRQUEZ / STRANGE PILGRIMS / REVIEW BY MICHIKO KAKUTANI

OBITUARIES / GABRIEL GARCÍA MÁRQUEZ

GARCÍA MÁRQUEZ / QUOTES / LIFE

GARCÍA MÁRQUEZ / QUOTES / FICTION

GARCÍA MÁRQUEZ / QUOTES / LITERATURE

GARCÍA MÁRQUEZ / QUOTES / ONE SINGLE FACT

GARCÍA MÁRQUEZ IN QUOTES

GARCÍA MÁRQUEZ TRIBUTES CELEBRATE LIFE AND WORK OF LITERARY GIANT

LATIN AMERICA REACTS TO DEATH OF LITERARY COLOSSUS GARCÍA MÁRQUEZ

GARCÍA MÁRQUEZ / FIVE MUST READS

Shakira by Gabriel García Márquez / The poet and the princess

SHORT STORIES

Gabriel García Márquez / One of these days

Gabriel García Márquez / Eva is inside her cat

Gabriel García Márquez / Eyes of a blue dog

Gabriel García Márquez / Tuesday Siesta

Gabriel García Márquez / A old man with enormous wings

Gabriel García Márquez / Light is like water

Gabriel García Márquez / Monologue of Isabel watching it Rain in Macondo

Gabriel García Márquez / Blacaman the Good, Vendor of Miracles

Gabriel García Márquez / Artificial Roses

Gabriel García Márquez / Ghosts of August

Gabriel García Márquez / The Airplane of Sleeping Beauty

Gabriel García Márquez / The Handsomest Drowned in the World

Gabriel García Márquez / Miss Forbes's Summer of Happiness

Gabriel García Márquez / The torment of Three Sleepwalker

Gabriel García Márquez / Night of the Stone-Curlews

SHORT STORIES IN SPANISH

Ojos de perro azul (1947 - 1955)

LA TERCERA RESIGNACIÓN (1947)

LA OTRA COSTILLA DE LA MUERTE (1948)

EVA ESTÁ DENTRO DE SU GATO (1948)

AMARGURA PARA TRES SONÁMBULOS (1949)

DIÁLOGO DEL ESPEJO (1949)

OJOS DE PERRO AZUL (1950)

LA MUJER QUE LLEGABA A LAS SEIS (1950)

NABO, EL NEGRO QUE HIZO ESPERAR A LOS ÁNGELES (1951)

ALGUIEN DESORDENA ESTAS ROSAS (1952)

LA NOCHE DE LOS ALCARAVANES (1953)

MONÓLOGO DE ISABEL VIENDO LLOVER EN MACONDO (1955)

Los funerales de la Mamá Grande (1962)

UN DÍA DE ÉSTOS (1962)

LA SIESTA DEL MARTES (1962)

EN ESTE PUEBLO NO HAY LADRONES (1962)

UN DÍA DESPUÉS DEL SÁBADO (1962)

LA PRODIGIOSA TARDE DE BALTASAR (1962)

ROSAS ARTIFICIALES (1962)

LA VIUDA DE MONTIEL (1962)

LOS FUNERALES DE LA MAMÁ GRANDE (1962)

La increíble y triste historia de Cándida Eréndira y de su abuela desalmada (1972)

UN SEÑOR MUY VIEJO CON UNAS ALAS ENORMES (1968)

EL MAR DEL TIEMPO PERDIDO (1961)

EL AHOGADO MÁS HERMOSO DEL MUNDO (1968)

MUERTE CONSTANTE MÁS ALLÁ DEL AMOR (1970)

EL ÚLTIMO VIAJE DEL BUQUE FANTASMA (1968)

BLACAMÁN EL BUENO VENDEDOR DE MILAGROS (1970)

LA INCREÍBLE Y TRISTE HISTORIA DE LA CÁNDIDA ERÉNDIRA Y DE SU ABUELA DESALMADA (1972)

Doce cuentos peregrinos

POR QUÉ DOCE CUENTOS PEREGRINOS

BUEN VIAJE, SEÑOR PRESIDENTE (1979)

LA SANTA (1981)

EL AVIÓN DE LA BELLA DURMIENTE (1982)

ME ALQUILO PARA SOÑAR (1980)

"SÓLO VINE A HABLAR POR TELÉFONO" (1978)

ESPANTOS DE AGOSTO (1980)

MARÍA DOS PRAZERES (1979)

DIECISIETE INGLESES ENVENENADOS (1980)

TRAMONTANA (1982)

EL VERANO FELIZ DE LA SEÑORA FORBES (1976)

LA LUZ ES COMO EL AGUA (1978)

EL RASTRO DE TU SANGRE EN LA NIEVE (1976)

Otros cuentos

GABRIEL GARCÍA MÁRQUEZ / EN AGOSTO NOS VEMOS

GABRIEL GARCÍA MÁRQUEZ / LA TIGRA

FICCIONES

Casa de citas / Paul Auster / Un recuerdo

Gay Talese / Mis dos encuentros con García Márquez

Casa de citas / García Márquez / Autorretrato

Casa de citas / García Márquez / Premio Cervantes 1997

Casa de citas / García Márquez / Vejez

Casa de citas / García Márquez / Mujeres

Casa de citas / César Vallejo / Contra García Márquez

Casa de citas / Bill Clinton / Confesión

Triunfo Arciniegas / Diario / El Gran Colombiano

Casa de citas / García Márquez / La buena pierna

Triunfo Arciniegas / Filósofo de semáforo / Políticos al fin y al cabo

Triunfo Arciniegas / Diario / García Márquez en Mester de Brevería

Diario / García Márquez por Triunfo Arciniegas

Triunfo Arciniegas / Diario / García Márquez en el Palacio de Bellas Artes

Triunfo Arciniegas / Diario / En agosto nos vemos

Triunfo Arciniegas / Diario / Breve consideración sobre "el gran colombiano"

Triunfo Arciniegas / Diario / Los cuartos del corazón

Triunfo Arciniegas / Diario / Lo que le debo a García Márquez

MESTER DE BREVERÍA

Gabriel García Márquez / El drama del desencantado

Gabriel García Márquez / Ladrón de sábado

Gabriel García Márquez / El prisionero

Gabriel García Márquez / Un chorro de luz dorada y fresca como el agua

Gabriel García Márquez / El fondo de la luz

Gabriel García Márquez / La bella durmiente

Gabriel García Márquez / El entierro

Gabriel García Márquez / Allí

Gabriel García Márquez / El otro

Gabriel García Márquez / Por fin

Gabriel García Márquez / Los cuartos infinitos

Gabriel García Márquez / El juego infinito

Natalia Deprina / Eva Is Inside her Cat

Cristina Tardáguila / Os vencedores dos prêmios Gabriel García Márquez de jornalismo

Cristina Tardáguila / A presença de Gabriel García MárquezGabriel García Márquez / En Aracataca, desdém pelo filho mais ilustre

Gabriel García Márquez / O escritor das rosas amarelas

Juan Gabriel Vásquez / Traga-me um livro de García Márquez

17 coisas que você não sabia sobre Gabriel García Márquez

Urariano Mota / O outono de Gabriel García Márquez

Gabriel García Márquez / Lembranças tropicais

Contos

Gabriel García Márquez / Olhos de cão azul

Gabriel García Márquez / Um senhor muito velho com umas asas muito grandes

Doze contos peregrinos

Boa viagem, senhor presidente

Gabriel García Márquez / A santa

Gabriel García Márquez / O avião da bela adormecida

Gabriel García Márquez / Me alugo para sonhar

Gabriel García Márquez / Só Vim Telefonar

Gabriel García Márquez / Assombrações de Agosto

Gabriel García Márquez / Maria dos Prazeres

Gabriel García Márquez / Dezessete ingleses envenenados

Gabriel García Márquez / Tramontana

Gabriel García Márquez / O Verão Feliz da Senhora Forbes

Gabriel García Márquez / A luz é como a água

Gabriel García Márquez / O rastro do teu sangue na neve

RIMBAUD

García Marquez est mort / «Ce qui importe, c’est la vie dont on se souvient»

Gabriel García Márquez / Un torrent de lumière dorée et fraîche comme de l'eau

Gabriel García Márquez / Le fond de la lumière

Gabriel García Márquez / La lumière est comme l'eau

Gabriel García Márquez / 1927 - 2014

Gabriel García Márquez / Un écrivain vissionnaire

Gabriel García Márquez / Cents ans de tristesse

Les secrets d'écrivain Gabriel García Márquez

Gabriel García Márquez / Cents ans de solitude / Extraits

Gabriel García Márquez / L'amour est ma seule idéologie

BIOGRAFÍAS

Gabriel García Márquez

Gabriel García Márquez

Gabriel García Márquez / La lumière est comme l'eau

Gabriel García Márquez / 1927 - 2014

Gabriel García Márquez / Un écrivain vissionnaire

Gabriel García Márquez / Cents ans de tristesse

Les secrets d'écrivain Gabriel García Márquez

Gabriel García Márquez / Cents ans de solitude / Extraits

Gabriel García Márquez / L'amour est ma seule idéologie

BIOGRAFÍAS

Gabriel García Márquez

Gabriel García Márquez

(6 March 1927 - 17 April 2014)

Latin-American journalist, novelist and short story writer, a central figure in the so-called Magic Realism movement. The term was first used in the 1920s Germany to describe some contemporary painters, whose works expressed surrealistic visions. In the late 1940s Cuban novelist Alejo Carpentier started to speak of "lo real maravilloso" (marvelous reality). Carpentier recognized the tendency of Latin-American writers to combine fantasy elements and mythology with otherwise realistic fiction. However, García Márquez has considered himself fundamentally a realist, who writes about Colombian and Latin American reality exactly as he has observed it.

"There is a short but telling portrait of the novelist Gabriel García Márquez, who every morning reads a couple of pages of a dictionary (any dictionary except the pompous Diccionario de la Real Academia Española) - a habit our author compares to that of Stendhal, who perused the Napoleonic Code so as to learn to write in a terse and exact style." (from A History of Reading by Alberto Manguel, 1996)

Gabriel García Márquez was born in Aracataca, in the "banana zone" of Colombia, the first child of Luisa Santiaga Márquez, the daughter of Colonel Nicolás Márquez, and Gabriel Eligio García, an itinerant homeopath and pharmacist. Soon after his birth, his parents left him to be reared by his grandparents and three aunts. García Márquez's grandfather admired greatly Simón Bolivar, and later the author portrayed the hero of South American independence in EL GENERAL EN SU LABERINTO (1989), which traced Simón Bolívar's final journey down the Magdalena river. From his grandmother he learned the oral tradition.

At the age of fifteen, he was sent to the Liceo de Zipaquirá, a high school for the gifted. He then studied law and journalism at the National University in Bogóta and at the University of Cartagena. While a law student in Bogota, he dressed like the celebrated singer and actor Carlos Gardel and frequented brothels. Once he was beaten when he failed to pay for the services. His first story, 'The Third Resignation', appeared in 1947. Next year he began his career as a journalist in Cartagena and Barranquilla, and then working in various towns in Latin America and Europe. For a period he secretly attended meetings of a Communist Party cell. One of his most famous reportages was an account of a young sailor, Luis Alejandro Velasco, who was swept off the Columbian destroyer Caldas into the Caribbean Sea. García Márquez was an European correspond in Rome and Paris for the newspaper El Espectador in 1955, but lost his post when the newspaper was closed down by the dictator Rojas Pinilla. Upon visiting the Soviet Union he concluded that the "Soviets have a different mentality. Things that are of great importance to us aren't to them." He was one of the founders of Prensa Latina, a Cuban press agency, and worked at Prensa Latina office in Havanna, where he befriended with Fidel Castro, and New York. Due to threatening phone calls from émigré right-wing Cubans García Márquez kept an iron rod by his desk. In 1958 he married Mercedes Barcha Pardo, the daughter of a pharmacist and granddaughter of an Egyptian immigrant. They had two children, Rodrigo, who became a film director, and Gonzalo, a graphic designer.

After working as editor-in-chief of Susesos and La Familia in Mexico City García Márquez continued his career as a screenwriter, journalist, and publicist. He also co-founded a film school near Havanna. For some years he lived Barcelona and returned to Mexico in the late 1970s, before he was officially invited by the new President, Belisario Betancur to Columbia, where he went in 1982 with his family. Although García Márquez has an apartment in Bogotá, most of his time he has spent in Mexico City and at his other homes, Cuernavaca, Havana, Barranquilla, Cartagena, Barcelona, and Paris. His house in Cartagena, built in the 1990s and called La Casa del Escritor, was designed by the Colombian architect Rogelio Salmona.

When sixty internationally renowed cultural figures condemned in 1971 the arrest of the Cuban poet Heberto Padilla, who was made to "confess" his "counterrevolutionary activity", García Márquez refused to add his name to their open letter to Castro. Also Julio Cortázar did not sign it. However, over the years García Márquez has used his influence to help secure the release of a number of Cuban political prisoners. "I am perhaps the one person Fidel can trust most in the world," he once said in an interview. Another political leader, with whom he associated, was General Omar Torrijos, who seized power in Panama in 1969. He participated in various ways in the campaing the have the famous canal and the adjoining areas placed under Panamanian sovereignty. García Márquez was godfather for Mario Vargas Llosa's second son, but a fist-fight with the Peruvian writer in a Mexican cinema in 1976 broke their relationship for decades. After Vargas Llosa was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 2010, García Márquez sent a message, saying that finally they are both equals.

García Márquez is known all over the Spanish speaking world as "Gabo". His first short stories were published in the 1940s. The novella LA HOJARASCA (1955, Leaf Storm) introduced to the public the fictional Colombian village of Macondo, an equivalent of William Faulkner's Yoknapatawpha. Since then it has been the setting in many of his later books. Márquez's early works, starting from Leaf Storm, went unnoticed by scholars and critics, despite their literary merits. From Alejo Carpentier Márquez learned to work with concurrent historical epochs and gradually influences from Faulkner gave way to his more objective manner of depiction, partly derived from his experiences in journalism. Other important writers, who have influenced García Márquez, include Kafka, Virginia Woolf, and Juan Rulfo.

In the short story 'Death Constant Beyond Love' (1970) Márquez sharply observed politics, poverty, and corruption. The protagonist, Senator Onésimo Sánches, is no hero – his electoral campaing is a circus, he takes bribes and helps the local property owners to avoid reform. "His measured, deep voice had the quality of calm water, but the speech that had been memorized and ground out so many times had not occurred to him in the nature of telling the truth, but, rather, as the opposite of a fatalistic pronouncement by Marcus Aurelius in the fourth book of his Meditations." (in Innocent Erendira and Other Stories, 1972). But Stoic understanding of the emptiness of his career doesn't help the senator, and he dies weeping with rage, without the love of Laura Farina, a village girl.

In 1982 García Márquez was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature. With his Nobel Prize money he bought in 1999 the weekly news magazine Cambio.

García Márquez's celebrated CIEN ANOS DE SOLEDAD (1967, One Hundred Years of Solitude) was first published by Editorial Sudamericana in Buenos Aires. It is the history of Macondo, depicted on a epic level, from its mythic foundation to its final disappearance. Combining the world of the bourgeois family chronicle and Latin American history it explores the limits of narrative fiction, wihout the sterility of the French nouveau roman. One Hundred Years of Solitude become one of the most popular works of Magic Realism. Ursula K. Le Guin said in an interview with Amazon.com: "That idea of "realism is literature and every other form of fiction is not literature" didn't get really badly shaken until the magical realists popped up in South America. When you've got García Márquez around, you just can't go on that way."

García Márquez once said, that he tries to tap "the magic in commonplace events." As fantastic as the events seem in the novel, they have much real basis, among them the massacre of hundreds of people, which occurred after the banana workers struck against the United Fruit Company in 1928. Some of the author's own relatives were on the side of the Americans and blamed the strikers for "sabotaging property". The lost historical consciousness of the villagers is exemplified in the chapter, in which the insomnia epidemic threatens to wipe out all layers of identity and culture. "It was foreseen that the city of mirrors (or mirages) would be wiped out by the wind and exiled from the memory of men at the precise moment when Aureliano Babilonia would finish deciphering the parchments, and that everything written on them was unrepeatable since time immemorial and forevermore, because races condemned to one hundred years of solitude did not have a second opportunity on earth."

Márquez's other major novels and novellas include EL OTOÑO DEL PATRIARCA (1977), an analysis of dictatorship on mythical and historical level. In the story a false death of the patriarch is followed by a second, apparently real, which leads to a new struggle of power. CRÓNICA DE UNA MUERTE ANUNCIADA (1981) recounted the murder of a man for allegedly violating the law of honour. Against these dramatic events Márquez sets a small town where everyday life continues in spite everyone knows a murder will happen. DEL AMOR Y OTROS DEMONIOS (1995, Love and Other Demons) was a historical novel set in the 18th century Colombia. Although One Hundred years of Solitude is among the most famous modern classics in the world, many consider EL AMOR EN LOS TIEMPOS DEL CÓLERA (1985, Love in the Time of Cholera), which drew on the courtship of his parents, most enduring book. In the novel their names were Florentino Ariza and Fermina Daza.

In July 1999 García Marquez was hospitalized and diagnosed with lymphatic cancer. A phony news flash went out through the Internet, claiming he had died in Mexico City. VIVIR PARA CONTARLA, the first part of his memoirs, was published in 2002. It spans the life of the author from his birth to the 1950s. After a long hiatus as a novelist, Márquez published MEMORIA DE MIS PUTAS TRISTES (2004), which was immediately translated into 18 languages. The narrator is a ninety-year-old man, who wants to have sex with a 14-year-old virgin. It is the gift he wants to give himself. Marquez's story of an old man and a young girl – a classical subject which goes back to the Book of the Kings and king David among others – stirred some controversy in Columbia.

KIRJASTO

|

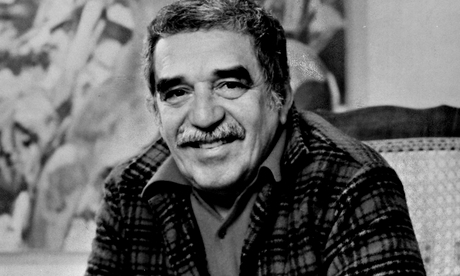

| Gabriel García Márquez, 2014 |

Gabriel García Márquez obituary

Colombian Nobel laureate who helped to launch boom in Latin American literature with novel One Hundred Years of Solitude

The Guardian, Thursday 17 April 2014 22.52 BST

Gabriel García Márquez in 1984.

Photograph: Ben Martin

Few writers have produced novels that are acknowledged as masterpieces not only in their own countries but all around the world. Fewer still can be said to have written books that have changed the whole course of literature in their language. But the Colombian writer Gabriel García Márquez, who has died at the age of 87 after suffering from Alzheimer's disease achieved just that, especially thanks to his novel One Hundred Years of Solitude.

Since its publication in 1967, more than 25m copies of the book have been sold in Spanish and other languages. For at least a generation the book firmly stamped Latin American literature as the domain of "magical realism".

Born in the small town of Aracataca, close to the Caribbean coast of Colombia, García Márquez (or "Gabo" as he was often affectionately nicknamed) always identified himself with the cultural mix of Spanish, black and indigenous traditions that continue to flourish there. Although later in life he lived in Paris, Mexico and elsewhere, his books returned constantly to this torrid coastal region, where the power of nature and myth still predominate over the restraints of cold reason.

This sense of identification with the Caribbean coast was strengthened by the fact that the young García Márquez was forced to leave it when he was eight, so marking out the period of his early childhood as the source of not only his most heartfelt memories, but as the wellspring for his literature. García Márquez has often recalled how, with his father absent as a telegraph operator, he was brought up by a grandfather who told him tales of his heroic deeds in Colombia's civil wars of the 19th century, and a grandmother whose every move was ruled by superstition. This combination of the ordinary and the extraordinary was the world that later resurfaced to such telling effect in One Hundred Years of Solitude and many other novels.

García Márquez's subsequent education took place in the capital, Bogotá, in the other, Andean part of Colombia. He always spoke of these years as of a cold, lonely exile. Forced to study law, he sought consolation in literature. At first, like many Colombians, he imagined himself a poet, until one day he discovered Franz Kafka and suddenly saw that everything was possible for the modern imaginative writer. Spurred on in this way, at the age of 20 he abandoned his law studies and from then on devoted himself to writing.

In the early 1950s he worked during the daytime as a newspaper reporter, first back on the coast and later in Bogotá on the newspaper El Espectador. His account of what had happened during the shipwreck of a Colombian naval vessel brought him renown as a journalist, but also got him into trouble with the authorities. This led to the start of a peripatetic and often wretchedly poor existence that lasted almost a decade. All the while, though, he was using the nights and any spare time to write fiction as well, and his first short novel, Leafstorm, was published in 1955.

Journalism was to remain a passion throughout his life: time and again his fictional stories have their basis in tales he heard as a young journalist, as he explains for example in the introduction to the 1994 novel Of Love and Other Demons. At the same time, whatever fantastic elements are to be found in his novels and short stories, García Márquez learned from journalism the craft of story-telling, showing himself to be an astounding judge of pace, surprise, and structure. He was also immensely interested in the cinema. In Rome in the 1950s he studied at the Experimental Film School, and while living in Mexico in the 1960s wrote several film scripts. He also dabbled in television soap operas, arguing that this was the way to reach the broadest possible audience and satisfy their need for narrative. In the early 1980s he helped found an International Film School near the Cuban capital of Havana. In 1994, he used some of the huge royalties his works had brought him to set up a school of journalism back on the Colombian Caribbean coast, at Cartagena de Indias.

But it is as a writer of fiction, enjoyed by everyone from untutored readers to academics in universities around the world, that García Márquez will be remembered. By the mid-1960s, he had published three novels that enjoyed reasonable critical acclaim in Latin America, but neither huge commercial nor international success. His fourth novel, One Hundred Years of Solitude, first published not in Colombia but in Argentina, was to change all that. It tells the story of succeeding generations of the archetypal Buendía family and the amazing events that befall the isolated town of Macondo, in which fantasy and fact constantly intertwine to produce their own brand of magical logic. The novel has not only proved immediately accessible to readers everywhere, but has influenced writers of many nationalities, from Isabel Allende to Salman Rushdie. Although the novel was not the first example of magical realism produced in Latin America, it helped launch what became known as the boom in Latin American literature, which helped many young and talented writers find a new international audience for their often startlingly original work.

As with many other descriptions of literary schools, magical realism eventually came to seem almost as much a curse as a blessing. García Márquez professed himself amazed at the success One Hundred Years of Solitude enjoyed, and declared that he considered his masterly study of Latin American tyranny in Autumn of the Patriarch (1975) to be a more complete work of art. Almost as powerful were the classical simplicity of Chronicle of a Death Foretold (1981), the tender exploration of the impossibilities of love in Love in the Time of Cholera (1985), or the study of the collapse of utopian dreams in The General in His Labyrinth (1994).

Those dreams were prominent in García Márquez's speech when he was awarded the Nobel prize for literature in 1982. In it, he made a passionate appeal for European understanding of the tribulations of his own continent, concluding that "tellers of tales who, like me, are capable of believing anything, feel entitled to believe that it is not yet too late to undertake the creation of a minor utopia: a new and limitless utopia wherein no one can decide for others how they are to die, where love can really be true and happiness possible, where the lineal generations of one hundred years of solitude will have at last and forever a second chance on earth".

García Márquez was also adamant that the writer had a public duty to speak out on political issues. His own views were strongly leftwing, opposed to what he saw as imperialism, particularly with regard to the domination of Latin America by the US. This distrust was reciprocated, and for many years, despite being one of the best-known writers among the reading public, he was denied access to the United States.

His socialist views led him to consistently back the Castro regime in Cuba, and he was a close personal friend of Fidel Castro. His faithfulness to the Cuban revolution led to him falling out with many of his own generation of Latin American writers, who became increasingly critical of the lack of intellectual freedom on the island. In response, García Márquez argued that he used his influence on the Cuban leader to secure the release of a large number of writers and other political prisoners from the island.

García Márquez was also passionately interested in the often tragic political situation of his own country. One of his early books In Evil Hour (1962) looks at the period of political violence in the 1950s, which caused over 100,000 deaths, and both in his fiction and his other writing he constantly looked for an end to the senseless killing.

After his period in exile during the 1950s, the violence of the 1970s also led him to spend most of his time outside the country. He helped founded a leftwing magazine, Alternativa, which promoted broadly socialist ideas, but never became directly involved in the political struggle. In the 1990s, as one of the few personalities his fellow Colombians actually trusted, he was several times mentioned as a possible presidential candidate, but always refused to lend himself to any campaign. Perhaps his most remarkable book about the political situation in Colombia was Noticia de un Secuestro (News of a Kidnapping, 1996) in which he describes in meticulous but passionate detail the kidnapping of 10 people by the drugs boss Pablo Escobar, and the complicated and only partly successful negotiations for their release. Few books reveal so chillingly the ability of the drugs mafia to penetrate to the very heart of society and pervert all its values.

His leftwing beliefs also led García Márquez to oppose military rule in the rest of Latin America. In 1975 he even claimed he would not write again until the Chilean dictator General Augusto Pinochet was removed from power (though he could not keep his word, and returned to publishing in 1981, with Chronicle of a Death Foretold). He also took a strongly anti-British line over the struggle for sovereignty in the Falkland islands in 1982.

Always outspoken in his public comments and in his journalism, García Márquez could also be immensely generous and warm in his private life. He was married to Mercedes, his childhood sweetheart, for over 40 years, and had two sons, Rodrigo and Gonzalo. He was famously loyal to his friends, but disdainful of all those whom he thought of as only being attracted to him because of his fame. Indeed, he often spoke of the difficulties and loneliness that international success had brought him, and sought whenever possible to keep his private world apart from it.

In 1999 the writer was diagnosed with lymphoma, or cancer of the immune system. The illness was to cloud his final years, requiring constant treatment. At times he was so ill that the international rumour mill not only proclaimed him to be at death's door several times, but apocryphal tales of his death-bed conversion to Catholicism circulated widely. Despite these rumours, he embarked on an ambitious autobiography.

Originally intended to be in three volumes, only the first, Vivir para Contarla (Living To Tell the Tale, 2002) came out, telling the story of his life up to his marriage with Mercedes. He also published Memorias de Mis Putas Tristes (Memories of My Melancholy Whores, 2004), but the very mixed reaction to his tale of a 90-year old and his liaison with a teenage prostitute convinced him that his writing days were over.

García Márquez's intense enjoyment of life shines through all his work, sometimes even seeming to be at variance with what is apparently its underlying message. As the title of his greatest novel tells us, its theme is the solitude and abandonment of Macondo, and yet the sheer appetite for life revealed in the characters and the storytelling itself speak instead of a huge wonder and enjoyment of existence. The millions of readers of García Márquez's books throughout the world appreciated above all that he wrote about immediately accessible themes such as love, friendship and death in a way that was new and yet plainly part of the great novel tradition. To many Latin Americans, García Márquez's work had the added importance of showing them that even if an author is born far from the centres of political and cultural power the sheer force of imagination can succeed in creating a world that will be magically recognised everywhere.

He is survived by a wife, Mercedes Barcha Pardo, and two sons, Rodrigo and Gonzalo.

Nick Caistor

Katharine Viner writes: Before the world discovered his prodigious imagination, Gabriel García Márquez was a brilliant journalist with a strong commitment to his first profession. He founded his Fundacion para un Nuevo Periodismo Iberoamericano in Cartagena on the Colombian coast to promote South American journalists, and it was at the foundation's 1999 conference on weekend journalism that I met Gabo, as he insisted we call him; as editor of Guardian Weekend magazine, I was the guest lecturer from Britain.

He was fabulous company: both aware of his stature and funny, gossipy and generous. He told wonderful stories about his great friend Castro – how Fidel refused to have US satellite TV in his home, but would go round to Gabo's Cuban house to watch it – mostly for the sport.

Gabo had strong views on what American culture was doing to the world, and especially to love, telling me, "What is killing relationships is dialogue. If you don't communicate then neither of you is forced to lie." But what was most charming about being in Gabo's company was how he engaged with you with a generosity rare among many lesser figures.

The fact of my vegetarianism seemed to throw him monumentally: "It cannot be true!" he said. "You lack the forlorn look of vegetarians!" We had a small row about this. And then another about a few other things (a photograph of us arguing sits proudly on my mother's wall). "You are a dictator!" he said. "I'm horrified," I replied. "No, it is a compliment. Because I am a dictator as well."

He made the week in Cartagena one of the most thrilling of my life; but it didn't end there. A few days after I got home, a little jaded at my desk, he rang me. "You are a journalist. You are the editor of a fine magazine. It is the finest job in the world!" he said. "I am calling to tell you that we love you, and we miss you, and the places where you went dancing in Cartagena are calling out for you every day." He was a man who knew how to make you feel good; and every kindness sounded like poetry.

Gabriel García Márquez, writer, born 6 March 1927; died 17 April 2014

“When grandmother told a story her face assumed an expression

that made one wonder what the matter was with her.

When I first wrote the story I was not satisfied.

It did not sound quite like her.

I resolved then to rewrite it once I had full grasp of her style.”

Gabriel García Márquez

“Writing the first paragraph is the hardest part of writing a novel.

Once the first paragraph has been written the narrative flows.

Writing short stories, by the same logic, is even harder

because you need an opening paragraph for every story.”

Gabriel García Márquez

Boom in U.S. for Latin Writers

By EDWIN McDOWELL

The New York Times

Published: January 4, 1988

Ralph Maheim, the great translator from the German, compared the translator to an actor who speaks as the author would if the author spoke English. A sophisticated and provocative analogy, for it takes into account something that is not always as clear as it should be, at least to many reviewers, whose highest endorsement for a translation tends to be that it is “seamless.” If I may attempt to translate the damnation barely concealed in their faint praise, I think they really mean that the translator has, with proper humility, made herself or himself “invisible,” a punishing goal that is desirable only if we are held personally responsible for the Tower of Babel and all its dire consequences for our species.

Ralph Maheim, the great translator from the German, compared the translator to an actor who speaks as the author would if the author spoke English. A sophisticated and provocative analogy, for it takes into account something that is not always as clear as it should be, at least to many reviewers, whose highest endorsement for a translation tends to be that it is “seamless.” If I may attempt to translate the damnation barely concealed in their faint praise, I think they really mean that the translator has, with proper humility, made herself or himself “invisible,” a punishing goal that is desirable only if we are held personally responsible for the Tower of Babel and all its dire consequences for our species.

Fidelity is surely our highest aim, but a translation is not made with tracing paper. It is an act of critical interpretation. Let me insist on the obvious: Languages trail immense, individual histories behind them, and no two languages, with all their accretions of tradition and culture, ever dovetail perfectly. They can be linked by translation, as a photograph can link movement and stasis, but it is disingenuous to assume that either translation or photography, or acting for that matter, are representational in any narrow sense of the term. Fidelity is our noble purpose, but it does not have much, if anything, to do with what is called literal meaning. A translation can be faithful to tone and intention, to meaning. It can rarely be faithful to words or syntax, for these are peculiar to specific languages and are not transferable.

Fidelity is surely our highest aim, but a translation is not made with tracing paper. It is an act of critical interpretation. Let me insist on the obvious: Languages trail immense, individual histories behind them, and no two languages, with all their accretions of tradition and culture, ever dovetail perfectly. They can be linked by translation, as a photograph can link movement and stasis, but it is disingenuous to assume that either translation or photography, or acting for that matter, are representational in any narrow sense of the term. Fidelity is our noble purpose, but it does not have much, if anything, to do with what is called literal meaning. A translation can be faithful to tone and intention, to meaning. It can rarely be faithful to words or syntax, for these are peculiar to specific languages and are not transferable.

To recreate significance for a new set of readers, translators must make the effort to enter the mind of the first author through the gateway of the text – to see the world trough another person’s eyes and translate the linguistic perception of that world into another language. The better the original writing, the more exciting and challenging the process is. You can be sure that the attempt to enter the mind of García Márquez is as exciting and challenging as the work of a translator gets.

To recreate significance for a new set of readers, translators must make the effort to enter the mind of the first author through the gateway of the text – to see the world trough another person’s eyes and translate the linguistic perception of that world into another language. The better the original writing, the more exciting and challenging the process is. You can be sure that the attempt to enter the mind of García Márquez is as exciting and challenging as the work of a translator gets.

His most recent book, Living to Tell the Tale, is the first volume of a projected three-volume memoir, though I am sure there will be those who insist that it is fiction, as some did, especially in the UK, when News of a Kidnapping was first published and people who should have known better refused to believe that the book was a piece of investigative reporting. The possible reason for their misapprehension is made explicit in Living to Tell the Tale: in a series of fascinating comments, García Márquez makes it clear that he sees little distinction between the practice of journalism and the writing of fiction. This is certainly not a question of his confusing truth and imagination, or reality and fantasy, and it is much more than a clever turn of phrase or thought. Over and over again in the memoir he refers to incidents and situations that are familiar to the reader because they have appeared, transmuted and transported, in the works of fiction. Even more important than events mined from the mother-lode of his experience, however, is the reportorial narrative technique common to both genres in García Márquez’ writing.

His most recent book, Living to Tell the Tale, is the first volume of a projected three-volume memoir, though I am sure there will be those who insist that it is fiction, as some did, especially in the UK, when News of a Kidnapping was first published and people who should have known better refused to believe that the book was a piece of investigative reporting. The possible reason for their misapprehension is made explicit in Living to Tell the Tale: in a series of fascinating comments, García Márquez makes it clear that he sees little distinction between the practice of journalism and the writing of fiction. This is certainly not a question of his confusing truth and imagination, or reality and fantasy, and it is much more than a clever turn of phrase or thought. Over and over again in the memoir he refers to incidents and situations that are familiar to the reader because they have appeared, transmuted and transported, in the works of fiction. Even more important than events mined from the mother-lode of his experience, however, is the reportorial narrative technique common to both genres in García Márquez’ writing.

He is a master of physical observation: Surfaces, appearances, external realities, spoken words – everything that a truly observant observer can observe. He makes almost no allusion to states-of-mind, motivations, emotions, internal responses: Those are left to the inferential skills and deductive interests of the reader. In other words, García Márquez has turned the fly-on-the-wall point of view into a crucial aspect of his narrative style in both fiction and non-fiction, and it is a strategy that he uses to stunning effect. It not only obliges readers to participate in the narration by placing them up on the wall, right next to the fly, but I believe it is also one of the techniques he employs to abrogate sentimentality, leaving only actions driven by emotions, and sometimes passions.

He is a master of physical observation: Surfaces, appearances, external realities, spoken words – everything that a truly observant observer can observe. He makes almost no allusion to states-of-mind, motivations, emotions, internal responses: Those are left to the inferential skills and deductive interests of the reader. In other words, García Márquez has turned the fly-on-the-wall point of view into a crucial aspect of his narrative style in both fiction and non-fiction, and it is a strategy that he uses to stunning effect. It not only obliges readers to participate in the narration by placing them up on the wall, right next to the fly, but I believe it is also one of the techniques he employs to abrogate sentimentality, leaving only actions driven by emotions, and sometimes passions.

It is a joy and a privilege beyond the telling of it to translate the profoundly expressive and artful writing of the Maestro. Thank you, Gabo, for your books.

It is a joy and a privilege beyond the telling of it to translate the profoundly expressive and artful writing of the Maestro. Thank you, Gabo, for your books.

KIRJASTO

The New York Times

Published: January 4, 1988

A half-dozen years ago, so many American publishers were issuing fiction by Latin American authors that critics dubbed the period the ''Latin boom.'' The boom inevitably subsided, but now it is returning stronger than ever - not just with more titles, but also with books that are already major critical or commercial successes in Latin America and Europe.

The rebirth will be most noticeable on or about Feb. 1, the publication date of Jorge Amado's ''Showdown'' - a worldwide best seller for which Bantam paid $250,000 two years ago, the highest price any American publisher had paid for rights to publish a foreign novel in hard cover.

Mr. Amado's presence will be widely apparent in American bookstores in 1988 for other reasons as well: Avon Books plans to issue 13 of his novels, beginning in March with the first English-language publication of ''Captains of the Sands,'' a book written exactly 50 years ago. Every month after that, it intends to reissue another Amado title in trade paperback. Garcia Marquez Novel

Another Latin author who will be prominent here in 1988 is Gabriel Garcia Marquez, the winner of the 1982 Nobel Prize in Literature. His new novel, ''Love in the Time of Cholera,'' also a worldwide best seller, is to be published by Alfred A. Knopf on April 29 with a first printing of 100,000 copies. It is also a main selection of the Book-of-the-Month Club, it will be excerpted in The New Yorker, and it has been optioned for a movie.

However, unlike Garcia Marquez's ''One Hundred Years of Solitude'' (1970), which has sold more than a million copies in its Avon paperback edition, ''Cholera'' is a much more conventional novel. ''It is a book that will stand the critics on their heads,'' said a specialist in Latin American literature at New York University, Alexander Coleman. ''But it reads like Balzac; there is no magic realism here.''

Magic realism is the term used to describe the Latin literary penchant for intertwining fact and fantasy, reality and illusion, legend and superstition. While magic realism is still in evidence, as it is evident in the fiction of some younger United States authors, literary sleight of hand is less dominant in the newer Latin novels. Emphasis on Story Over Style

''What I'm seeing is a trend toward a more traditional narrative line, emphasizing storytelling rather than the stylistic artistry that drew attention to Latin American literature,'' said the director of the literature program for the Americas Society, Lori Carlson.

Latin authors are still using the novel to discuss the region's social, economic and political problems, and publishers apparently hope that the widespread discussion of those problems in the American press will translate into the sale of books by Latin authors. Their hope and their receptivity to Latin authors are buttressed by the realization that Latin fiction is widely taught in comparative literature courses in the United States as well as in Latin studies programs.

''Not long ago it was hard for Latin writers to break through in this country,'' said Gregory Rabassa, who translated ''One Hundred Years of Solitude'' and ''Showdown.'' Speaking of the situation now, he added, ''Publishers from big and smaller presses are always asking me: 'Is there anything new? What should we be publishing?' ''

While the major commercial presses will be publishing more Latin authors than ever in 1988, Ms. Carlson said some university presses had recently discovered Latin literature -a discovery the University of Texas Press and a few others made years ago. Smaller Presses Join Trend

She also cited an increasing number of small commercial presses that publish distinguished Latin authors, including Carcanet Press in New York, Ediciones del Norte in Hanover, N.H., Log Bridge Rhodes in Albuquerque, City Lights Books in San Francisco, Unicorn Press in Greensboro, N.C., Bilingual Review/Press in Tempe, Ariz., and Curbstone Press in Willimantic, Conn.

New Directions, a distinguished small press in New York, has published the poetry of Octavio Paz of Mexico for more than 40 years. Four Walls Eight Windows, a small New York press, will soon publish ''Contemporary Fiction From Central America,'' edited by Rosario Santos, a Bolivian author and editor.

In addition to Jorge Amado, at least five other Brazilian authors are to be represented on the lists of American publishers in 1988. Late this month, Harmony Books is to publish ''The Strange Nation of Rafael Mendes'' by Moacyr Scliar, a public-health physician in Brazil; another of his novels, ''The Gods of Raquel,'' was just published by Ballantine Books. Aventura has scheduled two Brazilian novels for next spring: ''Mule'' by Darcy Ribeiro and ''Sempre Viva'' by Antonio Callado.'' Next fall, Harper & Row is to publish ''Long Live the Brazilian People,'' a novel by Joao Ubaldo Ribeiro. Argentines on the List

Several authors from Argentina are also to be represented. In April, Pantheon Books is to publish ''The Peron Novel'' by Tomas Eloy Martinez, and it is to publish a trade paperback edition of ''All Fires the Fire'' by Julio Cortazar, a novel published in English in 1973. In June, North Point Press is to publish ''Open Door,'' translations of 32 stories by Luisa Valenzuela. And Knopf has acquired but not yet set a publication date for ''The Dogs of Paradise,'' a novel by Abel Posse, who is also an Argentine author.

Next May, Weidenfeld & Nicolson is to publish ''Curfew'' by the Chilean author, Jose Donoso, a novel widely praised by Jacobo Timerman in his recent nonfiction book about Chile. That same month, Pantheon is to publish ''Century of the Wind,'' the third novel in a trilogy by Eduardo Galeano of Uruguay.

By year's end, Farrar, Straus & Giroux plans to publish ''Storyteller'' by Mario Vargas Llosa, the Peruvian novelist, and ''Christopher Unborn'' by Carlos Fuentes of Mexico. The publication date is pending for another Fuentes book, ''Constancia and Other Stories for Virgins.'' And From Exile Authors

It should not be surprising that exiled authors are on the publishers' lists. Avon, for example, recently published ''Biting Silence,'' a novel about military repression by Arturo Von Vacano, an exile from Bolivia. Next March, Viking Penguin plans simultaneous hard-cover and paperback editions of ''Last Waltz In Santiago and Other Poems of Exile and Disappearance'' by Ariel Dorfman, a Chilean exile, while Penguin is also to reprint Mr. Dorfman's novel ''The Last Song of Manuel Sendero.'' Next fall Knopf is to publish ''Eva Luna,'' a novel by Isabel Allende, another Chilean exile.

But the literary exile who will be most in evidence in 1988 is Reinaldo Arenas, who arrived in the United States on the Mariel boatlift from Cuba. Avon recently published his novel ''The Ill-Fated Peregrinations of Fray Servando,'' and next June Penguin is to reprint another of his novels, ''Singing From the Well.'' Meanwhile, Grove Press has signed up three books by Mr. Arenas - two novellas that it expects to publish next fall and a novel, ''The Doorman,'' scheduled for 1989.

While this ''Latin boom'' may also eventually subside, books by Latin authors are not likely to disappear from American publishing lists anytime soon. ''In the literature of the 20th century,'' said an editor at Knopf, Lee Goerner, ''Latin Americans are the equal of writers in any language or in any culture. And it's very hard for publishers to resist that.''

On Translation and García Márquez

By Edith Grossman

Speech delivered at the 2003 PEN Tribute to Gabriel García Márquez, held in New York City on November 5, 2003.

For further reading

Gabriel García Márquez: A Life by Gerald Martin (2009); Gabriel Garcia Marquez: A Critical Companion by Ruben Pelayo (2001); Tras las claves de Melquiades: Historia de Cien años de soledad by Eligio García Márquez (2001); The Modern Epic: The World-System from Goethe to Garcia Marquez by Franco Moretti (1996); García Márquez, ed. by Robin Fiddian (1995); Intertextuality in García Márquez by Arnold M. Penuel (1994); Circularity and Visions of the New World in William Faulkner, Gabriel Garcia Marquez, and Osman Lins by Rosa Simas (1993); Gabriel García Márquez: a Study of the Short Fiction by Harley D. Oberhelman (1991) Gabriel García Márquez: the Man and His Work by Gene H. Bell-Villas (1990); Gabriel García Márquez and the Invention of America by Carlos Fuentes (1987); Gabriel García Márquez by Raymond L. Williams (1984); Gabriel García Márquez: An Annotated Bibliography, 1947-1979 by Margaret Eustella Fau (1980); Gabriel García Márquez by George McMurrayu (1977) - English-language magic realists: Salman Rushdie, Brian Aldiss, James P. Blaylock, Peter Carey, Angela Carter, E.L. Doctorow, John Fowles, Mark Helprin, Emma Tennant. - Among acclaimed Latin American magic realists are Jorge Amado, Jorge Luis Borges, Isabel Allende, and Julio Cortázar.

KIRJASTO

WORKS

Novels

- In Evil Hour 1962

- One Hundred Years of Solitude 1967

- The Autumn of the Patriarch 1975

- Love in the Time of Cholera 1985

- The General in His Labyrinth 1989

- Of Love and Other Demons 1994

Novellas

- Leaf Storm 1955

- No One Writes to the Colonel published 1961 in Spanish (written in 1956-1957)

- Chronicle of a Death Foretold 1981

- Memories of My Melancholy Whores 2004

Short Story Collections

- Innocent Eréndira, and Other Stories 1978

- Collected Stories 1984

- Strange Pilgrims 1993

Non Fiction

- The Story of a Shipwrecked Sailor 1970

- The Solitude of Latin America 1982

- The Fragrance of Guava 1982, with Plinio Apuleyo Mendoza

- Clandestine in Chile 1986

- News of a Kidnapping 1996

- A Country for Children 1998

- Living to Tell the Tale 2002

A very good article about Gabo.... May I share an Interview with Gabriel Garcia Marquez (imaginary) in http://stenote.blogspot.com/2014/09/an-interview-with-gabriel.html

ResponderEliminarThanks for sharing wonderful info, Found your post interesting, can not wait to see more from you. Good luck for upcoming post!!! You can also read more from Putas en engativa

ResponderEliminar