|

| Edwin Morgan |

Edwin Morgan

(1920 - 2010)

Summary

Born Glasgow, Edwin Morgan lived there all his life, except for service with the RAMC, and his poetry is grounded in the city. Yet the title of his 1973 collection, From Glasgow to Saturn, suggests the enormous range of Morgan's subject matter. He was Glasgow's first Poet Laureate 1999-2002, and the first to hold the post of 'Scots Makar', created by the Scottish Executive in 2004 to recognise the achievement of Scottish poets throughout the centuries.

Full Biography

Scotland’s first official Makar in modern times, Edwin Morgan was endlessly inventive, inquiring, energetic, internationalist, and deeply committed to his home city of Glasgow.

A book of poems in his honour, Unknown Is Best, was produced to celebrate Morgan’s eightieth birthday in 2000. His own poem, ‘At Eighty’, was characteristic of the poet’s work, faring forward into the future, embracing change: ‘Push the boat out, compañeros / Push the boat out, whatever the seas…. push it all out into the unknown! / Unknown is best, it beckons best…’.

This seems an unlikely sentiment from a man of Morgan’s background. He was the only child of loving, anxious and undemonstrative parents, Stanley and Margaret (née Arnott) Morgan, politically conservative and Presbyterian. His father was a director of a small firm of iron and steel merchants. Edwin George Morgan was born on 27 April 1920 in Glasgow’s West End, and brought up in Pollokshields and Rutherglen. He attended – unhappily – Rutherglen Academy, moving on to complete his schooling at Glasgow High and entering Glasgow University in 1937. When he was called up in 1940, he horrified his family by registering as a conscientious objector. He reached a compromise position while waiting for his case to be called, and asked to serve in the RAMC, with which he spent the war in Egypt, the Lebanon and Palestine.

He was demobbed in 1946, returned to Glasgow and took a first class Honours degree in English Language and Literature. There was a chance of studying at Oxford, but Morgan preferred to take up the offer of a Lectureship in the Department of English at Glasgow University, where he remained. Having become Titular Professor in 1975, he retired from the University in 1980. He was a much-valued colleague and himself appreciated the structure and salary that academic life gave him.

Morgan first published under the name ‘Kaa’ in the High School of Glasgow Magazine, in 1936, and went on using that nom de plume in the Glasgow University Magazine, emerging as reviewer and translator under his own name in a variety of periodicals after the war. His first collection, The Vision of Cathkin Braes, was published by William MacLellan of Glasgow in 1952, and in the same year the Hand and Flower Press issued his translation of Beowulf (reissued by Carcanet Press in 2002). For fifty years Morgan maintained this double output, translations from Russian and Hungarian, Latin and French, Italian and Old English keeping pace with his own work, showing astonishing variety and technical skills in both. He won the Soros Translation Award in 1985, and spent the prize money on a day trip to Lapland on Corcorde.

That first collection seems quite mannered now, given the immediacy of voice that characterizes Morgan’s poetry as it developed. A Second Life, published handsomely by Edinburgh University Press in 1968, signalled a profound private change as well as public achievement: this was the volume that established Morgan’s importance. In 1963 he had met and fallen in love with John Scott, to whom he remained attached – although they never lived together – until Scott’s death in 1978. Given the repressive legislation and attitudes of the time, this was a concealed love, but for Morgan it represented a liberating reciprocity. It was paralleled by his discovery of the Beat poets and other American exemplars such as William Carlos Williams and Robert Creeley: from them, he said, ‘I really learned for the first time… that you can write poetry about anything.’

The subjects in A Second Life ranged from the dispossessed and marginalised populations of Glasgow, in all the misery of the tenements due for demolition, to the trio walking up Sauchiehall Street, ‘laughter ringing them round like a guard’ as well as poets, Marilyn Monroe and Edith Piaf. Some of his wittiest concrete poems – ‘Siesta of a Hungarian snake’, the classic ‘Computer’s First Christmas Card’ are here, and the love poems that are much loved, ‘Strawberries’, ‘One cigarette’. Kevin McCarra remarked of the devotion to the city Morgan lived in all his life:

It is part of his purpose to bear witness to Glasgow while insisting that hope and realism need not be at odds. This is tricky work and all his talent is required to hold off glibness. Misery, violence and pain are on the scene, but they will not be given the last word.

Unobtrusively yet significantly, Morgan’s wide reading, love of cinema and definite musical tastes all informed his poetry. Of poets writing in English, he was one of those most attuned to what changes science and technology have brought to our perception of the world. He was one of the first civilians to put his name down for a space-shuttle trip (yet he never used a computer). The title of his 1973 collection, From Glasgow to Saturn, not only suggests his subject range but also his curiosity. The scienc-fiction element in his poetry is one aspect of this, but there is also the interest in the whole history of earth, manifested in his Planet Wave sequence (1997) which was set to music by Tommy Smith. The energy of inquiry attracted him, and the energy of invention.

His concrete poetry was informed by correspondence with leading poets of the genre from Switzerland, Germany and Brazil, as well as in England and closer to hand with Ian Hamilton Finlay, whose Wild Hawthorn Press published Morgan’s first concrete poems in 1963. Inventing verse forms throughout his career – as late as Cathures (2002) he found a new stanzaic form – he was also a master of classic form. He demonstrated in his use of sonnets, particularly, how a construction in some ways ‘rigid and exoskeletal’ yet shows what is ‘living and provocative’ inside. The ‘Glasgow Sonnets’ are a brilliant example, while the Sonnets from Scotland (published by Hamish Whyte’s Mariscat Press in 1984) remain the most significant Scottish collection of that decade. They look on Scotland from the perspective of time-travellers or space-voyagers, and offer a view of utter change. The change in history is summed up in ‘The Coin’, one side showing the head of a red deer, on the other ‘the shock of Latin, like a gloss, / Respublica Scotorum…’ Morgan conjures up the prospect of an entirely different nation, in the same sequence as he had considered the 1979 referendum. The Sonnets, James Robertson has said, ‘were a hugely uplifting read during a politically frustrating time’.

It was in 1990 that Morgan ‘came out’ in an interview with Christopher Whyte. Not all Scottish attitudes had moved with the times: it was a shock to some and was revisited in the controversy over the Stobhill sequence about an abortion (the Daily Record protesting against the poems being read in schools) and when his play, AD, was performed to mark the millennium. Morgan’s life of Jesus was typically questioning and bold, and surprisingly his first complete play, though he was drawn to the theatre all his life. His poems were often dramatic monologues – as in the collection From the Video Box (1986) – and he translated several plays, including a bravura version of Cyrano de Bergerac. That play was almost all in Glaswegian Scots, a language Morgan moved in and out of with ease in his poetry, and relished for the range of expression it allowed him.

Morgan lived on his own and judged it best for his work that he should do so. Yet he was a public man, always ready to take part in readings, travel to schools, judge competitions. He enjoyed public recognition in the form of his OBE in 1982, the Queen’s Gold Medal in 2000, and being made the first Poet Laureate of Glasgow in 1999, and then of Scotland, as the Scots Makar, in 2004. His poem on the opening of the Scottish Parliament building is a model of public poetry, challenging and celebratory. The literary community of Scotland warmly admired him and his fellow-citizens regarded him with great affection; he was generously encouraging to younger writers, corresponding widely. Diagnosed with prostate cancer in 1999, he remained curious, even about that, and kept up his literary interests to the end. The energy of his last major collection, Love and a Life (Mariscat, 2003), was a testimony to many loves, and to the undiminished power of his imagination. This collection was included in A Book of Lives (Carcanet, 2007), shortlisted for the T.S. Eliot Prize.

He opened the Edwin Morgan Archive of printed and recorded material at the Scottish Poetry Library on his 89th birthday, and his 90th birthday party at the Mitchell Library, Glasgow also marked the publication of a gathering of uncollected and new work, Dreams and other Nightmares (Mariscat, 2010).

Morgan was widely recognised as the most influential poet of his gifted generation. His linguistic resources, formal invention, intellectual curiosity, sense of humour and humane vision combined to produce a poetry of extraordinary range and emotional reach.

‘Poetry is a brilliant vibrating interface between the human and the non-human.’

Edwin Morgan

Born in Glasgow, Edwin Morgan was expected to join the family shipping business, but began writing love poems instead. He served in the second world war, taught himself Russian and drew inspiration from the Beats. Acknowledged as Scotland's foremost living writer, he was this month named as the country's first poet laureate

James Campbell

Saturday 28 February 2004 01.27 GMT

Among the former pupils at Edwin Morgan's old school, Rutherglen Academy, was Stan Laurel. The diminutive half of the comic duo Laurel and Hardy was raised in the small town, now part of Glasgow, before he began to hone his comic timing in the city's music halls. Morgan's life could scarcely appear more different: until his retirement in 1980, he was professor of English at Glasgow university; he led a secretive existence as a homosexual before coming out at 70; he is the author of a large body of cerebral poetry, and translations from several languages, including Russian and Hungarian. Yet one of Morgan's poetic identities is as Scotland's, if not Britain's, best comic performer in verse. A public reading by Morgan might involve poems such as "The Loch Ness Monster's Song", with its sensitive rendering of the voice of the world's loneliest beast, or "The Clone Poem", based on the conceit, "when you've seen one you've seen them all seen them all seen one seen them all all all all", or else Instamatic Poems or Newspoems or Science Fiction Poems. By the time Morgan gets to "French Persian Cats Having a Ball" - "chat / shah shah / chat / chat shah cha ha", reprised in playful combinations - members of the audience are likely to be having at least as much fun as those who heard Laurel's jokes in the pre-first world war music hall.

Morgan is far from being just a stand-up poet, however. He has written poems of great feeling, such as "The Death of Marilyn Monroe", which rolls forward in lumbering cadences like a funeral cortège led by a Scottish Allen Ginsberg: "And if she was not responsible, not wholly responsible, Los Angeles? / Los Angeles? Will it follow you around? Will the slow / white hearse of the child of America follow you around?" He has also produced works expressing the inner life of Glasgow, in which cloth cap and fur coat make a happy couple, and "Monsters of the year / go blank" before the vision of a holy trio of young people and a chihuahua (rather than a donkey) in the city centre at Christmas time. In addition to all this, Morgan has written concrete poetry, computer poetry and an 80-part serial work, Sonnets from Scotland (1984), with titles ranging from "The Picts" to "De Quincey in Glasgow" to "Gangs". There's a different voice on every page and they're all Morgan's. This month, Morgan was named poet laureate of Scotland, the first incumbent, by Jack McConnell, first minister of Scotland. The obligations of laureateship are not new to him. In 1999 he was made poet laureate of the city of Glasgow, and performed the role with typical enthusiasm. The latest honour only makes official something that has been widely acknowledged for some time, that Morgan is Scotland's foremost living writer.

"Morgan's poetry comes at you from every conceivable corner of time and space and in every imaginable mode," says Colin Nicholson, professor of English at Edinburgh and author of a study of Morgan's work, Inventions of Modernity (2002). "To use his own phrase, no matter where we look in the universe there is 'nothing not giving messages'. Everything in his imagined cosmos is capable of speech: Rousseau's ghost, the devil at Auschwitz and Percy Shelley. Mao's cat speaks, so does a crack in glass. Who else in poetry has made science fiction into such a fruitful territory for expression?"

As Morgan reached his 83rd birthday last year, he left his flat of many years, off Glasgow's Great Western Road, and took up residence in a nursing home in Bearsden, an imposing Gothic pile where he has a pleasant room on the ground floor. He made the decision to desert his book-lined nest only because, being less physically robust than before, he was afraid of a fall. In every other way, he is quite as mercurial as ever - his speech running fast to keep up with his thoughts and recollections. A hint of a smile lingers perpetually about his face, which seems to belong to a younger man. Until recently, he sported flaring sideburns, like a 50s rock 'n' roll singer.

From the moment he attained a degree of literary eminence, Morgan has made himself available to poetry's younger seekers, his combination of reliability and generosity mingling with a distinct personal reserve. "He is a man who wants to say 'Yes', if at all possible," says the poet and novelist Ron Butlin. "In essence, Eddie is a shy man, and his support was often on paper rather than in person. For example, when with the brashness of youth I wrote to ask him if he would write the foreword to my first collection of poems in the 1970s - I hardly knew the man - he agreed at once. This kind of support to unknown writers is rare, and Morgan does it frequently."

Born in Hyndland, in Glasgow's West End, in 1920, his family moved to the then-independent burgh of Rutherglen two years later. His father, like many Glaswegians of the time, worked in shipping. "On long walks, he used to tell me all about how steel was made and how ships were constructed," Morgan recalls. "That industrial side of Glasgow was in my mind from a very early age." Hamish Whyte, owner of the small Mariscat Press, which has published Morgan's work since 1982 (his more extensive collections are published by the Manchester firm Carcanet), feels the ever-changing city of Glasgow is a "constant" in the poet's life. "He's made us look at the city in a different way, always an oblique way, making the ordinary extraordinary. Glasgow suits him. It's always reinventing itself. Change Rules OK, as Eddie once said."

The future envisaged by the elder Morgans for their only child was in the firm of Arnott, Young and Co, iron and steel merchants and shipbreakers, where his father started out as a clerk and his mother was the boss's daughter. Neither parent had much interest in literature. "My father liked stories with lots of politics in them, which he would hold up as if they were real. He had a strange idea that fiction wasn't really fiction. He would say: 'How terrible it is about such-and-such a country, because I read about it in this novel.' They knew that I was writing things, from a young age, but I wasn't given any particular encouragement. I think my mother wished I'd go out and kick a ball, instead of writing about it." He describes his childhood as "very much an unhappy one". Material hardship did not affect him, just a deeply felt lack of communication. "My mind was buzzing with ideas, but I couldn't talk to people about them. All sorts of things: astronomy, zoology, archaeology. I grew up in the great age of Egyptian discoveries and I was fascinated by that - but I couldn't find anyone to discuss it with." According to Whyte, Morgan "doesn't display ego or a big personality. He seems self-effacing - which is perfect for his writing, for it enables him to be anything, from an apple to Rameses II."

By his late teens, Morgan was "pretty sure" he was "going to do something with poetry", but the war interrupted both his artistic ambitions and the education that was likely to further them. Having enrolled at Glasgow university in 1937, he didn't graduate until a decade later. In between, he served in the Royal Army Medical Corps in the Middle East.

His first book, The Vision of Cathkin Braes, was brought out in 1952 by the Glasgow publisher of MacLellan, discoverer of many a mid-century Scottish gem. The title poem is an extraordinary work of some 300 lines, in which the poet and "my honey" retire to the braes, or hills, near Rutherglen and hide among "the trees and thickets, eerie and dim" to make love. One after another, iconic figures from Scottish history and legend appear to them, including John Knox, Mary Queen of Scots and the poet McGonagall, on the back of a bull. He announces himself, in character, "to you maybe a figure somewhat comical, / But as you see here I am riding a dangerous beast / With two horns, innumerable teeth, internal combustion, and a wild tail, to say the least".

The early 1950s were, by most accounts, unexciting for Scottish writing, "not a very thrilling or throbbing period", as Morgan puts it. "It was just at the end of the war. A lot of people were picking up loose ends. I don't think I was terribly aware of what was happening in Scotland. My main contact was with the poet WS Graham, who lived in Cornwall. Hugh MacDiarmid was always in the background, but I didn't know much about him until later. His books were hard to get hold of."

Stronger influences came from Wales - "Dylan Thomas was the last really popular great poet" - and the United States, where a chorus of rebellious voices was rising. The last place Morgan was likely to look for inspiration was England. "I was no admirer of Larkin and his crew at all," he says, with a rare expression of distaste. "At the time, the English critics were hailing everything Larkin was doing, but it didn't make much impact on me. I was looking for something else, and when Ginsberg and Ferlinghetti and Corso and others appeared in America, that was more like the thing that would interest me. There was nothing like that in Scotland, or in England either. I liked the outspokenness of the Beats. When Ginsberg's Howl [1957] appeared, it had words that could hardly be printed at all. I was attracted by the idea of someone taking risks in poetry, which seemed to me the very opposite of what the Larkin lot were doing in England."

Another powerful force from the US was William Carlos Williams, a poet with an instinct to explore his own locality. Morgan understood that "Williams was doing something with the place where he lived that I could apply to the place where I lived. He influenced me in being able to write about very ordinary things in Glasgow. I had never thought of that kind of approach before. At school, poetry was mostly Romantic poetry, it was exalted, it was about love and nature and great subjects - not about the slums of Glasgow."

The work of the Beat poets still seems in many ways an unexpected resource for a man who was a career academic in a conventional English department, and who was to become Scotland's most celebrated living poet. Morgan resembles Ginsberg in the desire to capture a visitation, sparked perhaps by something simple - a programme on television, the smoke from a lover's cigarette, even a misprint in someone else's poem ("Little Blue Blue", for example, is based on the misprinted title of Norman MacCaig's poem "Little Boy Blue"). But there was something yet more urgent in the "Howl" of Ginsberg, and in the answering calls of certain contemporaries, that spoke to Morgan. The "honey" with whom he slips into the bushes in the "The Vision of Cathkin Braes", to exchange "tender kisses", was male. Love poetry is one of the principal elements in Morgan's work, but until his coming out in 1990, as a kind of 70th birthday present to himself, his readers were invited to assume that the object of desire was female.

"I wrote these poems with the thought that they'd be understood one day," he says. "If I'd been completely inhibited, I wouldn't have written them. The other aspect is that the secrecy, the double-life thing, had a dramatic side to it. You could write about that too, sometimes, in a shadowed way." He mentions, as an example, "Glasgow Green", a poem about a male rape. It was first published in the 60s, when homosexuality was illegal, but, says Morgan, "it is quite clear, if you look closely, what it's about. It described a nightmarish scene, in a way, but there's a kind of urban drama about that. I remember that when I wrote it, even though I was pretty confident it was a good poem, it took me a while to send it out to a magazine. Now it's taught in schools."

Some readers claim to have discerned "coded" references to the gay life in Morgan's early romantic poetry, and indeed, returning to a poem such as "Christmas Eve", published in the early 70s, the modern reader might think it odd that there was ever any mystery about his sexual orientation. On a bus on Christmas Eve, while "cars all dark with parcels" stream home to families, a man places his hand on the poet's knee, where it stays until they are both ejected by the conductor:

"It was only fifteen minutes out of life

but I feel as if I was lifted by a whirlwind

and thrown down on some desert rocks to die

of dangers as always far worse lost than run."

The Scottish poet and critic Christopher Whyte (no relation to Hamish), author of an essay, "The Love Poetry of Edwin Morgan", says no other Morgan poem of the time "reaches this degree of explicitness. With few exceptions, Morgan sticks to the rules he has set himself, using the neutral pronoun 'you' throughout." One such poem is "From the North", in which the speaker imagines his desired one in pursuit of another adventure: "This Saturday on what corner / will you meet your next friend?"

Morgan says that, contrary to what people might imagine, "there was quite an active gay scene in the 50s and 60s - surprisingly active, if you think of Scotland as being a Calvinist country. In Glasgow, especially, there was always a very 'going' scene, involving not just gay men but married men who enjoyed gay company. That kind of thing has only recently emerged, but it was always there, even when I was quite young. There was a lot going on, but it was hugger-mugger. It was hidden." For 16 years, he had a partner, John Scott, the subject of many poems, "not a literary man at all. He worked as a storeman in factories, and so on." Many of Morgan's encounters are with working-class men; the seducer on the bus in "Christmas Eve" is a former soldier, tattooed, with a face "unshaven, hardman, a warning". A more recent poem, from his latest book Love and a Life (2003), has a reluctant suitor pleading "Ah love ma wife an ma weans".

To Christopher Whyte, the "fascinating doubleness" of Morgan's earlier love poems is lost in the more explicit confession. "They are less transgressive," he writes. "Gay men of Morgan's generation experienced an intensity of repression which gave even the simplest of gestures a stolen quality, as if the impossible had been realised." For his part, Nicholson finds "a greater emotional clarity" in the more recent work. Talking of the personal, rather than poetical, Ron Butlin says that "once he came out and started to relax, Eddie would host jolly suppers at his flat. He began to gossip and tell stories. Quite a different man from when I first met him."

Despite the example of Ginsberg, or of a poet nearer his own cultural experience such as Thom Gunn, Morgan did not seriously consider coming out until after his retirement from the university, where he was titular professor of English from 1975 to 1980. In the final line of the title poem of his 1968 collection A Second Life , he wrote: "Slip out of the darkness, it is time". He did not do so until much later, however. "It was in the late 1980s that I began to think, well, yes, I'll do something about this. I knew that in 1990, with my 70th birthday, there would be interviews, and I thought it was just absurd not to talk about my whole character and my whole experience." It was Christopher Whyte who broached the subject. "He said, would you like to talk about that some time, and I said 'Yes', without thinking about it. The time must have come."

Morgan's Collected Poems , published in the same year as he decided to admit to his "whole experience", 1990, is matched by an almost equally hefty volume, Collected Translations (1996). It contains work from, among other languages, Hungarian, Italian, French, Spanish and Anglo-Saxon. Morgan produced a formal English Beowulf in 1952, but the German of Heinrich Heine and the Russian of Vladimir Mayakovsky and others are rendered into broad Scots. One of Heine's simple songs comes out like this:

"Yonder's a lanely fir-tree

On the Hielan moors sae bare.

It sleeps in the snaw and the cranreuch

Wi a cauld cauld plaid to wear."

He taught himself Russian in his spare time in the 30s, with the intention of reading Russian literature, particularly the futurist poets such as Mayakovsky and the linguistically acrobatic Velimir Khlebnikov. Morgan situates this influence at the foundation of his development. "That was the beginning. But there was also the change that was taking place in Russian poetry in the 50s, people like Voznesensky and Yevtushenko, whose reputation has gone down now, but who at the time were very big figures. The Russian poetry scene was having a new lease of life at the same moment as the American Beats were emerging. And the third strand, if you like, was concrete poetry. All three things interested me."

Morgan began to correspond with Haroldo de Campos in Brazil, one of the pioneers of concrete poetry. The genre is notoriously factional, and not all sides favour Morgan's style. "I felt it was possible to have a clearer intellectual content in concrete poetry than you often find. I was trying to say you can write a poem which formally is strange, which involves very careful plotting of letters and space and so on, but nevertheless it is a poem, with ideas and history and human feeling. Some concrete writers don't like that idea at all." In the view of Professor Max Naenny, who taught concrete poetry at the University of Zurich, "Morgan is one of the leading concrete poets, and has extended the field considerably. Anyone who enjoys the playful use of letters, spaces and typographical outlines on a page - and this is what concrete poetry is all about - will cherish his poems." As Morgan says, "there is a purist side to concrete poetry, which is very different to what I do, and which I like, but I felt I wanted to give it a bit more body." A typical Morgan concrete poem is "The Computer's First Christmas Card", from 1968, which begins:

"j o l l y m e r r y

h o l l y b e r r y

j o l l y b e r r y"

and ends, after many attempts:

"C h r i s m e r r y

a s M E R R Y C H R

Y S A N T H E M U M"

He has also given us a pictorial representation of the "Siesta of a Hungarian Snake":

"s sz sz SZ sz SZ sz ZS zs Zs zs zs z"

The poems Morgan has translated from Hungarian constitute the body of foreign work of which he is probably most proud. As with Russian, he taught himself, using a dictionary and a bilingual anthology of poems - Italian-Hungarian. He has since translated several significant Hungarians into English, including Sandor Weores, whose Selected Poems Morgan issued in 1970. Weores and others seemed to him to be writing "a new kind of urban poetry", which Morgan attempted to emulate in his own poetry set in Glasgow.

In the midst of this multifarious activity, Morgan was teaching at Glasgow university. It is easily forgotten that many of the great 20th-century Scottish poets - MacCaig, Sorley MacLean, Iain Crichton Smith, Robert Garioch - were teachers (schoolteachers, in those cases). Morgan now describes his literary work, with a weary chuckle, as taking place "in the interstices of life. Promotion was very slow in those days. Our professor was not a great one for pushing his staff forward. It was a demanding job. English was a huge class, and what with marking essays and exam papers ... it wasn't easy. There were times when I thought I should pack it in and become a freelance. But I liked the job of teacher. I was quite good at it. I liked the students. It was a living. Whereas it would have been a tremendous risk, casting off into the wilds of journalism. Partly, I may not have done it because I was afraid." He declares himself in favour of the young poet having a recognisable job, and against the emergence of the "university poet". He has seen examples "of poets who have been sucked into the academic life, and have had it damage their poetry. I think I was helped by living in a big city like Glasgow, where the university is not on a campus. As soon as the day's lecturing is done, you're back among the strange and fascinating and even dangerous life of the city."

Were it not for the extraordinary cosmopolitanism of his mind, one might think that in Morgan's conversation all roads lead back to Glasgow. His room at the nursing home is brightened by a portrait of him in a Glasgow setting by the novelist and painter Alasdair Gray. In 2002, he published Cathures, a collection of poems mostly emerging from his Glasgow laureateship. Cathures (the city's original name) also contained a sequence of poems inspired by the cancer that had been revealed, including one about a seagull that perched on poet's windowsill one day, to take a "cold inspection":

"Perhaps he was, instead, a visitation

which only used that tight firm forward body

to bring the waste and dread of open waters,

foundered voyages, matchless predators,

into a dry room."

Morgan writes swiftly. The 50 poems of his latest book, Love and a Life, were written in less than three months. His output encompasses two collections of essays - one of which, Crossing the Border (1990), is devoted to Scottish literature - and several plays. He has also rendered Cyrano de Bergerac (1992) and Racine's Phaedra (2000) into lapel-grabbing Glaswegian. Recently, he has been working in partnership with the jazz saxophonist Tommy Smith to create works fusing poetry and music. The pair buzz ideas backwards and forwards, mostly by fax, until the piece is ready to be taken on tour. The whole notion of performance poetry, in which these collaborations are one more element, would have seemed alien to the Scottish poets with whom Morgan is commonly grouped. MacCaig, Crichton Smith and others were sensitive readers of their own work, but Morgan added a theatrical dimension. "That was again the Beats," he says. "I'd read all about their exploits in performance. Although they published their work in the normal way, they made a big thing about the live event, and about reaction from the audience, and this clicked with me. I began to think I could do something with this."

Born: April 27 1920, Glasgow.

Education: Rutherglen Academy; High School of Glasgow; University of Glasgow.

Career: 1940-46 RAMC; '50-75 lecturer in English, University of Glasgow; '75-80 Titular Professor of English, Glasgow, now Emeritus.

Poetry: 1952 The Vision of Cathkin Braes; '61 The Whittrick; '68 The Second Life; '72 Instamatic Poems; '73 From Glasgow to Saturn; '77 The New Divan; '79 Star-Gate: Science Fiction Poems; '84 Sonnets from Scotland; '87 Newspoems; '90 Collected Poems; '91 Hold Hands Among the Atoms; 2002 Cathures; '03 Love and a Life. Criticism: 1974 Essays; '90 Crossing the Border: Essays on Scottish Literature. Translation: 1952 Beowulf; '59 Poems from Eugenio Montale; '72 Wi the Haill Voice (Mayakovsky); '92 Cyrano de Bergerac; '96 Collected Translations.

Some Prizes: 1968 Cholmondeley Award; '72 Hungarian PEN Memorial Medal; 2000 Queen's Gold Medal for Poetry.

Edwin Morgan obituary

Scotland's national poet, he combined intellectual curiosity with emotional power

James Campbell

Thursday 19 August 2010 18.23 BST

Edwin Morgan, who has died aged 90, was the last of a group of great Scottish poets, spanning two generations, sometimes referred to as "the seven poets". His colleagues were Norman MacCaig, Iain Crichton Smith, Sorley MacLean, George Mackay Brown, Robert Garioch and Hugh MacDiarmid. The distinctive feature of this purely literary grouping (some individual members openly disliked others) was its astonishing variety. MacDiarmid is rightly cited as the sun around which the lesser planets revolved, and MacCaig commands a special affection on account of his wit and geniality, but Morgan was unrivalled in his formal invention, linguistic resourcefulness and – not the least of his qualities – his sense of fun. To read a book such as The Second Life (1968) was like going out to play. Here is Summer Haiku, for example:

Pool.

Peopl

e plop!

Cool.

This is Siesta of a Hungarian Snake:

s sz sz SZ sz SZ sz Zs zs Zs zs zs z

Morgan was born into a middle-class family in Hyndland, in Glasgow's west end. His family moved to nearby Rutherglen two years later, where he attended Rutherglen academy. Like many Glaswegians of the time, his father worked in shipping. When I interviewed Morgan in 2003 at the nursing home where he was then living, also in the west end, he spoke of the long walks he took with his father, on which "he used to tell me all about how steel was made and how ships were constructed. That industrial side of Glasgow was in my mind from a very early age."

As a youth, he was attracted to subjects such as astronomy, zoology and archaeology, but his parents intended their only child to follow them into the firm of steel merchants and shipbreakers, Arnott, Young and Co, where his father had started out as a clerk and his mother was the boss's daughter. He described his childhood, which was perhaps more study-bound than is thought to be normal, as "very much an unhappy one".

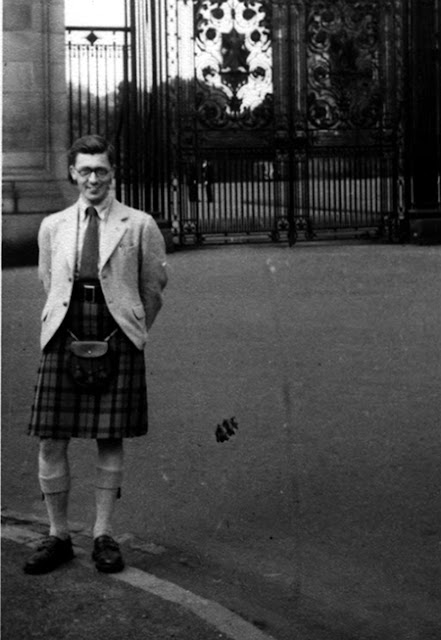

In contrast to the poetic congress babbling behind his spectacles and buck-toothed grin, Morgan in company could be reserved to the point of silence, especially among strangers. He had the look of being always slightly out of fashion. For 30 years, until his retirement in 1980, he taught at Glasgow University, eventually becoming titular professor of English in 1975. In addition to his own poetry, he translated from several languages, and in 1952 published a version of Beowulf.

He found his natural subject matter in the history and geography of Scotland, and in particular Glasgow. He was a skilled performer of his own work, much of which depends on complex verbal effects. Among Rutherglen academy's old boys was Stan Laurel, and it is nice to think that Morgan shared something of his comic sense of timing.

A public reading by Morgan might involve poems such as The Loch Ness Monster's Song, with its sensitive rendering of the voice of the world's loneliest beast; The Clone Poem, based on the conceit "when you've seen one you've seen them all seen them all seen one seen them all all all all"; or French Persian Cats Having a Ball – "chat / shah shah / chat / chat shah cha ha", reprised in rolling combinations.

He also produced poems of deep feeling, such as The Death of Marilyn Monroe, which goes forward in lumbering cadences like a funeral cortege led by a Scottish Allen Ginsberg: "And if she was not responsible, not wholly responsible, Los Angeles? / Los Angeles? Will it follow you around? Will the slow white / hearse of the child of America follow you around?"

Then there was the series of works expressing the inner life of Glasgow, in which cloth cap and fur coat make a happy couple, in which "Monsters of the year / go blank" before the vision of a holy trio of young people and a chihuahua (rather than a donkey) in the city centre at Christmas time. In addition, he wrote concrete poetry, computer poetry and an 80-part serial work, Sonnets from Scotland (1984), with titles ranging from De Quincey in Glasgow to Gangs.

Morgan enrolled as an undergraduate at Glasgow University in 1937 but his studies were interrupted by the second world war, in which he served in the Royal Army Medical Corps in the Middle East. His first book, The Vision of Cathkin Braes (the Braes is a range of hills on the southern outskirts of Glasgow), was published in 1952 by the Glasgow firm MacLellan. The title poem is an extraordinary work of around 300 lines, in which the poet and "my honey" retire to the Braes and hide among "the trees and thickets, eerie and dim" to make love. One after another, iconic figures from Scottish history and legend appear to them, including John Knox, the poet William McGonagall, on the back of a bull, and Mary, Queen of Scots.

Morgan more than once expressed his lack of enthusiasm for "Larkin and his crew", and his preference for Scots, Welsh and American bards. For linguistic effervescence, in the early days, he looked to WS Graham and Dylan Thomas; for the licence to write about "very ordinary things in Glasgow", he followed the example of William Carlos Williams. And from Williams he moved on to the beat generation – an unexpected step at that time for a career academic in a conventional English department.

Morgan resembles Ginsberg in the desire to capture a visitation, sparked perhaps by something on television, or the smoke from a lover's cigarette. But there was something yet more urgent in the Howl of Ginsberg that spoke to Morgan. The "honey" with whom he slips into the bushes in the The Vision of Cathkin Braes, to exchange "tender kisses", was male. Love poetry is one of the principal elements in Morgan's work, but until his coming out in 1990, as a kind of 70th birthday present to himself, his readers were invited to assume that the object of desire was female.

His love poems were nevertheless written with the hope that they would be understood one day, and attentive readers even in the 1970s would have had little doubt about a poem such as Christmas Eve, which recounts a story in which a man on a bus puts his hand on the poet's knee. Outside, "cars all dark with parcels" stream home to families:

It was only fifteen minutes out of life

but I feel as if I was lifted by a

whirlwind

and thrown down on some desert rocks

to die

of dangers as always far worse lost

than run.

For 16 years, Morgan had a regular partner, John Scott, the subject of several poems. He died in 1978. Morgan described him as "not a literary man at all. He worked as a storeman in factories, and so on." Many of Morgan's encounters are with working-class men; the man on the bus in Christmas Eve is an ex-soldier, tattooed, with a face "unshaven, hardman, a warning". A poem from his book Love and a Life (2003) has a reluctant suitor protesting his love for his wife and "ma weans".

In the 1930s, Morgan taught himself Russian, with the intention of reading the literature. He had a particular liking for the futurist poets, such as the linguistically acrobatic Velimir Khlebnikov. Morgan's Collected Poems, published by Carcanet in 1990, is matched by an almost equally hefty volume, Collected Translations (1996), in which, among much else, the reader will find the songs of Heinrich Heine rendered into broad Scots:

Yonder's a lanely fir-tree

On the Hielan moors sae bare.

It sleeps in the snaw and the cranreuch

Wi a cauld cauld plaid to wear.

Morgan was among the most prolific of modern poets, yet until his retirement from the university, his literary activity had to take place "in the interstices of life". Promotion was slow, the job was demanding, and there were times when he considered quitting and becoming a freelance writer, but he liked the steady living and being among the students. He declared himself in favour of poets having recognisable jobs and against the emergence of the university-subsidised poet.

Morgan was appointed OBE in 1982. In 1999, he was made Glasgow's first poet laureate and the following year he was awarded the Queen's gold medal for poetry. In 2004, he was named "Scots Makar", the national poet for Scotland. His collection Cathures (2002) contained poems mostly emerging from his laureateship and included a sequence inspired by the cancer which had lately been disclosed. His last collection of poetry, Dreams and Other Nightmares, was published earlier this year. As well as poems and translations, he published two collections of essays (one of which, Crossing the Border (1990), is devoted to Scottish literature), plays and Glaswegian versions of Rostand's Cyrano de Bergerac (1992) and Racine's Phèdre (2000).

Morgan was always quick to help younger poets, by reading their work, providing inspirational texts, and even writing a foreword when a book was ready to go into print. My encounters with him were mainly as editor: first for the quarterly magazine the New Edinburgh Review, to which he contributed poems and reviews, and later for the Times Literary Supplement. The last request I made of him was for a review of a book of newly discovered poems by MacDiarmid, to which he at first agreed, but later he admitted he was too weak to continue.

The most vivid memory snapshot of him I possess comes from long before then: one Saturday night in Glasgow in the 70s, after the pubs had closed, I boarded a bus heading out west. The upper deck, as always, was a genial riot of drinking songs, Frank Sinatra tunes, Danny Boy and the rest. In the middle of it all, hands clasped on his lap, sat a silently smiling Edwin Morgan.

• Edwin George Morgan, poet, born 27 April 1920; died 19 August 2010

Further Reading

Selected Bibliography

The Vision of Cathkin Braes and other poems (Glasgow: William MacLellan, 1952)

The Second Life (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1968)

Instamatic Poems (London: Ian McKelvie, 1972)

From Glasgow to Saturn (Cheadle: Carcanet Press, 1973

Essays (Cheadle Hume: Carcanet New Press, 1974)

Crossing the Border: essays on Scottish literature (Manchester: Carcanet Press, 1990)

Collected Poems (Manchester: Carcanet Press, 1990)

Collected Translations (Manchester: Carcanet Press, 1996)

Cathures: new poems 1997-2001 (Manchester: Carcanet Press, in association with Mariscat Press,

2002)

A Book of Lives (Manchester: Carcanet Press, 2007)

From Saturn to Glasgow: fifty favourite poems by Edwin Morgan, eds Robyn Marsack & Hamish

Whyte (Edinburgh: Scottish Poetry Library, in association with Carcanet Press, 2008)

Dreams and Other Nightmares: new and uncollected poems 1954-2009 (Edinburgh: Mariscat

Press, 2010)

Selected Biography and Criticism

Robin Fulton, ‘Edwin Morgan’ in Contemporary Scottish Poetry: individuals and contexts

(Loanhead: Macdonald Publishers, 1974)

Robert Crawford and Hamish Whyte (eds), About Edwin Morgan (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1990)

Hamish Whyte (ed.), Nothing Not Giving Messages: reflections on work and life (Edinburgh, Polygon, 1990)

Colin Nicholson, ‘Living in the utterance: Edwin Morgan’ in Poem, Purpose and Place: shaping

identity in contemporary Scottish verse (Edinburgh: Polygon, 1992)

Marshall Walker, ‘Poems and spaceships: Edwin Morgan’ in Scottish Literature Since 1707

(London and New York: Longman, 1996)

Colin Nicholson, Edwin Morgan: inventions of modernity (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2002)

Christopher Whyte, ‘The 1960s’ in Modern Scottish Poetry (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2004)

Colin Nicholson, ‘Edwin Morgan’s Sonnets from Scotland: towards a republican politics’ in Marco Fazzini, (ed.), Alba Literaria: a history of Scottish literature (Venezia Mestre: Amos Edizioni,2005)

Roderick Watson, ‘New visions of old Scotland: Edwin Morgan’ in The Literature of Scotland: the

twentieth century, 2nd edn,(Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2007)

Matt McGuire and Colin Nicholson, ‘Edwin Morgan’ in Matt McGuire and Colin Nicholson (eds),

The Edinburgh Companion to Contemporary Scottish Poetry (Edinburgh: Edinburgh

University Press, 2009)

Attila Dósa, ‘Edwin Morgan: our man in Glasgow’ in Beyond Identity: new horizons in modern

Scottish poetry (Amsterdam/ New York: Rodopi, 2009)

Robyn Marsack and Hamish Whyte, eds, Eddie @ 90 (Edinburgh: Scottish Poetry Library and Mariscat Press, 2010)

James McGonigal, Beyond the Last Dragon: a life of Edwin Morgan (Dingwall: Sandstone Press, 2010)