|

| Dorothy Parker |

KISS

DRAGON

FICCIONES

DE OTROS MUNDOS

Enrique Vila-Matas / Barcelona y Dorothy Parker

Manuel Vicent / Dorothy Parker / El humo de lejanas fiestas

Elvira Lindo / Las huellas de Dorothy Parker

Dorothy Parker según Marion Meade

Dorothy Parker / Colgando de un hilo / Reseña

Narrativa completa / Incorregible Dorothy Parker

Enrique Vila-Matas / Barcelona y Dorothy Parker

Manuel Vicent / Dorothy Parker / El humo de lejanas fiestas

Elvira Lindo / Las huellas de Dorothy Parker

Dorothy Parker según Marion Meade

Dorothy Parker / Colgando de un hilo / Reseña

Narrativa completa / Incorregible Dorothy Parker

Poemas

Cuentos

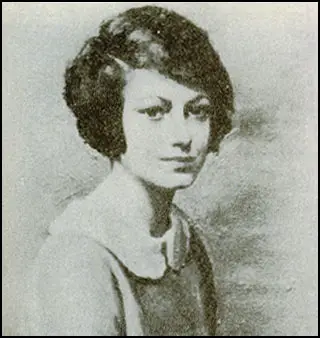

Dorothy Parker

Short Biography

(1893 - 1967)

On August 22, 1893, Dorothy Parker was born to J. Henry and Elizabeth Rothschild, at their summer home in West End, New Jersey. Growing up on Manhattan’s Upper West Side, her childhood was an unhappy one. Both her mother and step-mother died when she was young; her uncle, Martin Rothschild, went down on the Titanic in 1912; and her father died the following year. Young Dorothy attended a Catholic grammar school, then a finishing school in Morristown, NJ. Her formal education abruptly ended when she was 14.

In 1914, Dorothy sold her first poem to Vanity Fair. At age 22, she took an editorial job at Vogue. She continued to write poems for newspapers and magazines, and in 1917 she joined Vanity Fair, taking over for P.G. Wodehouse as drama critic. That same year she married a stockbroker, Edwin P. Parker. But the marriage was tempestuous, and the couple divorced in 1928.

In 1919, Parker became a founding member of the Algonquin Round Table, an informal gathering of writers who lunched at the Algonquin Hotel. The “Vicious Circle” included Robert Benchley, Harpo Marx, George S Kaufman, and Edna Ferber, and was known for its scathing wit and intellectual commentary. In 1922, Parker published her first short story, “Such a Pretty Little Picture," for Smart Set.

When the New Yorker debuted in 1925, Parker was listed on the editorial board. Over the years, she contributed poetry, fiction and book reviews as the “Constant Reader.”

Parker’s first collection of poetry, Enough Rope, was published in 1926, and was a bestseller. Her two subsequent collections were Sunset Gun in 1928 and Death and Taxes in 1931. Her collected fiction came out in 1930 as Laments for the Living.

During the 1920s, Parker traveled to Europe several times. She befriended Ernest Hemingway, F. Scott Fitzgerald, socialites Gerald and Sarah Murphy, and contributed articles to the New Yorker and Life. While her work was successful and she was well-regarded for her wit and conversational abilities, she suffered from depression and alcoholism and attempted suicide.

In 1929, she won the O. Henry Award for her autobiographical short story “Big Blonde.” She produced short fiction in the early 1930s, and also began writing drama reviews for the New Yorker. In 1934, Parker married actor-writer Alan Campbell in New Mexico; the couple relocated to Los Angeles and became a highly paid screenwriting team. They labored for MGM and Paramount on mostly forgettable features, the highlight being an Academy Award nomination for A Star Is Born in 1937. They divorced in 1947, and remarried in 1950.

Parker, who became a socialist in 1927 when she became involved in the Sacco and Vanzetti trial, was called before the House on Un-American Activities in 1955. She pleaded the Fifth Amendment.

Parker was inducted into the American Academy of Arts and Letters in 1959 and was a visiting professor at California State College in Los Angeles in 1963. That same year, her husband died of an overdose. On June 6, 1967, Parker was found dead of a heart attack in a New York City hotel at age 73. A firm believer in civil rights, she bequeathed her literary estate to Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Upon his assassination some months later, the estate was turned over to the NAACP.

POETS

POETS

Dorothy Parker

(1893 - 1967)

Dorothy Rothschild, the daughter of Jacob Rothschild, a successful businessman, was born in Long Branch, New Jersey on 22nd August, 1893. It was a premature birth and she later admitted that "it was the last time she was early for anything". Her mother died in July 1898.

In 1900 her father remarried. Dorothy had an unhappy childhood and later accused her father of being physically abusive. According to John Keats, the author of You Might as Well Live: The Life and Times of Dorothy Parker (1971): "She regarded her father as a monster. She was terrified of him. She could never speak of her father without horror. She was treated like a remittance child, if not like a child brought up in an orphanage administered by psychopaths. If the household held no love for her, neither did it have a place for her, for there was nothing she could do in the house. In the 1890s, the daughters of affluent families were most certainly not instructed in the domestic arts... She was taught that it was polite to be on time; dinner was at six thirty, and if Dorothy was not there, seen but not heard, precisely at six thirty, her father would hammer her wrists with a spoon."

Dorothy's stepmother was a devout Roman Catholic and she was sent to a boarding school run by nuns, the Blessed Sacrament Convert. She later recalled: "Convents do the same things progressive schools do, only they don't know it. They don't teach you how to read; you have to find that out for yourself. At my convert we did have a textbook, one that devoted a page and a half to Adelaide Ann Proctor; but we couldn't read Dickens; he was vulgar, you know. But I read him and Thackeray... As for helping me in the outside world, the convent taught me only that if you spit on a pencil eraser it will erase ink... All those writers who talk about their childhood! Gentle God, if I ever wrote about mine, you wouldn't sit in the same room with me.... I was fired from there, finally, for a lot of things, among them my insistence that the Immaculate Conception was spontaneous combustion."

Dorothy Rothschild was now sent to Miss Dana's School in Morristown, New Jersey. There was only fifteen girls to a class and each received considerable personal attention. Moreover, the classes were in the form of a seminar, with students and teachers sitting together at tables, "so that learning proceeded with a kind of easy, living-room informality". The school made "serious efforts to turn out well-read, well-informed, and well-spoken young women who would be effective in the world".

One of her classmates later recalled that "Dorothy was most attractive. She was small, slender, dark-haired, and brilliant. She was in the last class that was graduated from Miss Dana's before Miss Dana died and the school went bankrupt. I admired her as being an attractive girl; she was peppy and she was never bored. She was outstanding in school work, but I can't remember her playing games."

While at school she began writing poems. She sent them off to magazines and in 1916 she had one accepted by Frank Crowninshield, the editor of Vanity Fair: "Mr. Crowninshield, God rest his soul, paid twelve dollars for a small verse of mine and gave me a job on Vogue at ten dollars a week. Well, I thought I was Edith Sitwell. I lived in a boarding-house at 103rd and Broadway, paying eight dollars a week for my room and two meals, breakfast and dinner."

Dorothy wore glasses at work because she was badly near-sighted. However she always took them off when anyone stopped at her desk, and she never wore them on social occasions. Her outward reasons were expressed in the couplet: "Men seldom make passes/At girls who wear glasses." As one critic pointed out: "The couplet expressed contempt for men and despair over woman's lot. So it was a report of the immemorial human condition, and... appropriately sardonic."

At the time Dorothy was greatly influenced by the work of Edna St. Vincent Millay: "Like everybody else was then, I was following in the footsteps of Edna St Vincent Millay, unhappily in my own horrible sneakers.... We were all being dashing and gallant, declaring that we weren't virgins, whether we were or not. Beautiful as she was, Miss Millay did a great deal of harm with her double-burning candles. She made poetry seem so easy that we could all do it. But, of course, we couldn't."

In 1917 she married Edwin Pond Parker, who worked as a stockbroker in Wall Street. Some of her friends liked Edwin. Donald Ogden Stewart commented that he "was quite good-looking; very shy; he was modest; he was just a nice person to have around". Other friends worried about his heavy drinking. At the time Dorothy did not drink. Soon afterwards he joined the US Army and served in Europe during theFirst World War in the 33rd Ambulance Company and took part in most of the main battles on theWestern Front in 1918. The marriage was not successful and Parker had a series of love affairs. She once told a friend that she only "married him to change my name."

In 1918 Parker replaced P.G. Woodhouse as theatre critic of Vanity Fair. The editor, Frank Crowninshield, commented: "We, as a nation have come to realize the need for more cheerfulness, for hiding a solemn face, for a fair measure of pluck, and for great good humour. Vanity Fair means to be as cheerful as anybody. It will print humour, it will look at the stage, at the arts, at the world of letters, at sport, and at the highly vitalized, electric, and diversified life of our day from the frankly cheerful angle of the optimist, or, which is much the same thing, from the mock-cheerful angle of the satirist."

During this period she began having lunch with two other colleagues on the magazine, Robert Benchleyand Robert E. Sherwood, in the dining room at the Algonquin Hotel. Sherwood was six feet eight inches tall and Benchley was around six feet tall, Parker, who was five feet four inches, once commented that when she, Sherwood and Benchley walked down the street together, they looked like "a walking pipe organ."

According to Harriet Hyman Alonso , the author of Robert E. Sherwood The Playwright in Peace and War(2007): "John Peter Toohey, a theater publicist, and Murdock Pemberton, a press agent, decided to throw a mock "welcome home from the war" celebration for the egotistical, sharp-tongued columnist Alexander Woollcott. The idea was really for theater journalists to roast Woollcott in revenge for his continual self-promotion and his refusal to boost the careers of potential rising stars on Broadway. On the designated day, the Algonquin dining room was festooned with banners. On each table was a program which misspelled Woollcott's name and poked fun at the fact that he and fellow writers Franklin Pierce Adams (F.P.A.) and Harold Ross had sat out the war in Paris as staff members of the army's weekly newspaper, the Stars and Stripes, which Bob had read in the trenches. But it is difficult to embarrass someone who thinks well of himself, and Woollcott beamed at all the attention he received. The guests enjoyed themselves so much that John Toohey suggested they meet again, and so the custom was born that a group of regulars would lunch together every day at the Algonquin Hotel."

Murdock Pemberton later recalled that he owner of the hotel, Frank Case, did what he could to encourage this gathering: "From then on we met there nearly every day, sitting in the south-west corner of the room. If more than four or six came, tables could be slid along to take care of the newcomers. we sat in that corner for a good many months... Frank Case, always astute, moved us over to a round table in the middle of the room and supplied free hors d'oeuvre... The table grew mainly because we then had common interests. We were all of the theatre or allied trades." Case admitted that he moved them to a central spot at a round table in the Rose Room, so others could watch them enjoy each other's company.

The people who attended these lunches included Parker, Robert E. Sherwood, Robert Benchley,Alexander Woollcott, Heywood Broun, Harold Ross, Donald Ogden Stewart, Edna Ferber, Ruth Hale,Franklin Pierce Adams, Jane Grant, Neysa McMein, Alice Duer Miller, Charles MacArthur, Marc Connelly,George S. Kaufman, Beatrice Kaufman , Frank Crowninshield, Ben Hecht, John Peter Toohey, Lynn Fontanne, Alfred Lunt and Ina Claire. This group eventually became known as the Algonquin Round Table.

Parker developed a reputation for making harsh comments in her reviews and on 12th January 1920 she was sacked by Frank Crowninshield. He told her that complaints about her reviews had come from three important theatre producers. Florenz Ziegfeld was particularly upset by Parker's comments about his wife, Billie Burke: "Miss Burke is at her best in her more serious moments; in her desire to convey the girlishness of the character, she plays her lighter scenes as if she were giving an impersonation of Eva Tanguay."

Robert E. Sherwood and Robert Benchley both resigned over the sacking. As John Keats, the author ofYou Might as Well Live: The Life and Times of Dorothy Parker (1971): "It is difficult now to imagine a magazine of Vanity Fair's importance then truckling to Broadway producers, but the newspapers and magazines of 1920 did, and this was a sore point to the working newspapermen and theatre critics at the Round Table. They believed that if an actor was guilty of overacting, it was no more and no less than a critic's duty to report that he was - producers be damned. Furthermore, in this case, Vanity Fair's position seemed to be one of accepting a complaint from an advertiser as sufficient excuse to fire an employee with no questions asked, and it was the injustice of this position that led Mr Benchley and Mr Sherwood to tell Mr Crowninshield that if he was going to fire Mrs Parker, they were quitting."

Parker and Benchley rented a small office together. Benchley commented: "One cubic footless of space, and it would have constituted adultery." A few weeks later he abandoned the economically precarious existence of a free-lance writer and accepted the post as drama editor on Life Magazine. It was said that after Benchley left, Parker was very lonely and she decided to move in with the artist, Neysa McMein as her relationship with her husband was over. Donald Ogden Stewart commented: "It was a case of incompatibility. It just didn't work. When we got back from Germany, it was already over."

Parker later moved into her own apartment on West Fifty-Seventh Street. It was very small but she said all she needed was enough space "to lay a hat - and a few friends". It was a cheapley furnished room and apart from "her clothing and toilet articles, the only things in the room that belonged to her were her portable typewriter and a canary she called Onan because he spilled his seed upon the ground." Her only outings during this period involved going to the theatre with Alexander Woollcott and Robert Benchley, as they were always assigned two free seats when reviewing plays.

Parker remained in demand and worked for the New Yorker, The Nation, The New Republic, Cosmopolitanand American Mercury, became well-known for her acerbic criticism. Parker once commented thatKatharine Hepburn in a Broadway play: "She ran the whole gamut of the emotions from A to B." Parker also had a reputation for spontaneous wit. When told of the death of President Calvin Coolidge, she replied: "How could they tell?" She also said that a certain actress "speaks eighteen languages and can't say 'No' in any of them."

Parker relied heavily on her sense of humor in her writing: "Humor to me, Heaven help me, takes in many things. There must be courage; there must be no awe. There must be criticism, for humor, to my mind, is encapsulated in criticism. There must be a disciplined eye and wild mind. There must be a magnificent disregard for your reader, for if he cannot follow you, there is nothing you can do about it."

Parker remained a member of the Algonquin Round Table. They played games while they were at the hotel. One of the most popular was "I can give you a sentence". This involved each member taking a multi syllabic word and turning it into a pun within ten seconds. Dorothy Parker was the best at this game. For "horticulture" she came up with, "You can lead a whore to culture, but you can't make her think." Another contribution was "The penis is mightier than the sword." They also played other guessing games such as "Murder" and "Twenty Questions". A fellow member, Alexander Woollcott, called Parker "a combination of Little Nell and Lady Macbeth."

On 30th April 1922, the Algonquin Round Tablers produced their own one-night vaudeville review, No Siree!: An Anonymous Entertainment by the Vicious Circle of the Hotel Algonquin . It included a monologue byRobert Benchley, entitled The Treasurer's Report . Marc Connelly and George S. Kaufman contributed a three-act mini-play, Big Casino Is Little Casino , that featured Robert E. Sherwood. The show included several musical numbers, some written by Irving Berlin. One of the most loved aspects of the show was the Dorothy Parker penned musical numbers that were sang by Tallulah Bankhead, Helen Hayes, June Walker and Mary Brandon.

One of her closest friends during this period was Donald Ogden Stewart. He later recalled: "Dottie was attractive to everybody - the eyes were so wonderful, and the smile. It wasn't difficult to fall in love with her. She was always ready to do anything, to take part in any party; she was ready for fun at any time when it came up, and it came up an awful lot in those days. She was fun to dance with and she danced very well, and I just felt good when I was with her, but I think if you had been married to Dottie, you would have found out, little by little, that she really wasn't there. She was in love with you, let's say, but it was her emotion; she was not worrying about your emotion. You couldn't put your finger on her. If you ever married her, you would find out eventually. She was both wide open and the goddamnedest fortress at the same time. Every girl's got her technique and shy, demure helplessness was part of Dottie's - the innocent, bright-eyed little girl that needs a male to help her across the street. She was so full of pretence herself that she could recognize the thing. That doesn't mean she did not hate sham on a high level, but that she could recognize pretence because that was part of her make-up. She would get glimpses of herself doing things that would make her hate herself for that sort of pretence."

Gilbert Seldes agreed with Stewart about Parker who he considered to be "a sad person, unable to take real pleasure - as if being enormously satisfied with anything would be in her character, or would have diminished her". Seldes assumed correctly that Parker had great difficulty writing: "She was not the kind of person who could just sit down and write, as at a job. She was in the tradition of fiction as one of the beaux-arts."

In 1922 Dorothy Parker fell in love with the young journalist, Charles MacArthur. Her friend, Donald Ogden Stewart, remembers: "Charley was something else... Charley was marvellous. He was something all his own, and she was so in love it was really a serious, desperate thing. When Dottie fell in love, my God, it was really the works. She was madly in love. She was not a slave to love, exactly; it wasn't a game, exactly; it was really for keeps. She fell in love so deeply: she was wide open to Charley."

John Keats, the author of You Might as Well Live: The Life and Times of Dorothy Parker (1971) pointed out: "Charles MacArthur was a tall, handsome, talented, and altogether charming member of the Algonquin group. In 1922, he was a young newspaperman who dreamed of becoming a playwright and Dorothy Parker adored him... MacArthur, at that time, was a womanizer, which is a bit different from being simply an extremely eligible bachelor." The relationship eventually came to an end and Dorothy went through a period of depression. Stewart recalled: "I was sorry for her about Charley because she did love him terribly... She was suffering. She was having a hell of a time."

In 1924 Parker wrote the start of a play, Close Harmony, and sent it to the producer, Philip Goodman. He asked the successful playwright, Elmer Rice, if he was willing to work with Parker on the project. He recalled in an autobiography, Minority Report (1964): "Dorothy Parker had written a first act which Goodman felt had great promise but lacked theatrical craftsmanship... The characters, suburbanites all, just went on talking and talking. But they were sharply realized, and the dialogue was uncannily authentic and very funny. Since I have always enjoyed the technical side of playwriting, I agreed to Goodman's proposal; not without some misgiving, however, for, though I had never met Dorothy, I had heard tales about her temperament and undependability." Parker was thrilled when she heard that Rice had accepted the job: "I felt so proud.... I was just trembling all the time because Elmer Rice had done so many good things."

Rice was surprised by Parker's professionalism: "To my relief, everything went smoothly. She was punctual, diligent and amiable; no collaboration could have been less painful.... we had a good work routine. Every few days we went over what she had written, line by line, pruning out irrelevancies and reorganizing. Then we discussed the next scene in minute detail, and she went off to write it. She was unfailingly courteous, considerate and, of course, amusing and stimulating. It was hard to believe that this tiny creature with the big, appealing eyes and the diffident, self-effacing manner was capable of corrosive cynicism and devastating retorts. I discovered that in the granite of her misanthropy there was a vein of softish sentimentally. Our relationship was cordial and easygoing, but entirely impersonal."

According to Marion Meade, the author of Dorothy Parker: What Fresh Hell is This? (1989) Parker actually began an affair with Rice while writing the play: "Dorothy was not particularly attracted to Rice physically because he was not her type. She preferred tall, slim, cinematically beautiful blonds. Rice was a dour sex-foot, red-haired, bespectacled Jew... Against her inclination and better judgment, she finally went to bed with him, but it was one of those cases in which she realized her mistake at once. They were far less compatible sexually than artistically. Dorothy got little pleasure from their several encounters... Once having begun the affair, the problem became delicate: how to end it without wounding his feelings or, far more important, without jeopardizing her play."

Close Harmony opened at the Gaiety Theatre on 1st December, 1924 and ran for only 24 performances. During its three-week run the total receipts were less than $10,000. The rental charge on the theatre was over $4,000 a week and the producers lost a significant sum on the play. Ring Lardner wrote to Scott Fitzgerald saying that it received great reviews but still failed to attract audiences. Elmer Rice wrote that its failure was "inexplicable". It did much better on tour and played fifteen weeks in Chicago and another ten in smaller Midwestern cities.

Seward Collins, a journalist who it was claimed had a collection of pornography that was said to be the largest in the world, developed a fascination for Parker. However, the author of Dorothy Parker: What Fresh Hell is This? (1989) has pointed out that: "Dorothy had known Collins casually for several years but paid him slight attention. Not only was he six years her junior, but he was undistinguished physically, being of medium height and pale, mousy coloring. He had an ingratiating smile and was a talker, which annoyed some people, but his friends found him witty and amusing." At the time Parker rejected Collins as she was having a passionate affair with Deems Taylor who was married to the actress, Mary Kennedy. She was also sleeping with the writer, Ring Lardner.

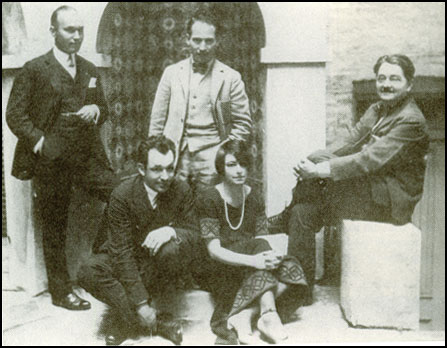

Harpo Marx and Alexander Woollcott (1924)

In 1925 Woollcott purchased most of Neshobe Island in Lake Bososeen. Most weekends he invited friends to the island to play games. Vincent Sheean was a regular visitor to the island. He claimed that Parker did not enjoy her time there: "She couldn't stand Alec and his goddamned games. We both drank, which Alec couldn't stand. We sat in a corner and drank whisky... Alec was simply furious. We were in disgrace. We were anathema. we ween't paying any attention to his witticisms and his goddamned games."

Parker became sexually involved with Seward Collins after she ended her affair with Taylor. An extremely wealthy man he gave her many gifts that included a beautiful wristwatch studded with diamonds. Collins also worked as her agent and arranged for her short-story, The Wonderful Old Gentleman, to be sold to the Pictorial Review, where it appeared in January 1926.

Later that year Collins took her on holiday to France and Spain. When they were in Barcelona he took her bullfighting. However, she walked out in protest when the first bull was killed. She told him that she could not understand why he had brought her to witness the killing of defenceless animals when he knew she could not bear their slightest mistreatment. When he replied that the bulls sometimes killed matadors, she commented that they deserved it.

The couple spent Easter in Seville. Parker later recalled that she was appalled by its poverty and backwardness. She also hated the "repulsive habit" of Spanish men pinching women's bottoms. It got so bad that she hated walking the streets. At the same time, she disliked spending time in the hotel room with Collins. Parker had discovered that Collins was not a lover who improved with extended contact.

They then moved on to Paris where they stayed at the Lutetia Hotel near the Luxembourg Gardens.Seward Collins used his time searching for items for his collection of erotica. Dorothy disapproved of this and during one argument she pulled off the diamond watch he had given her and flung it out of the window. Humiliated by the experience, Collins now decided to go home, leaving Parker to follow him later.

Parker's first collection of poems, Enough Rope (1926), received some great reviews. The Nation said that in the book's best lyrics "the rope is caked with a salty humor, rough with splinters of disillusion, and tarred with a bright black authenticy." Marie Luhrs, writing in Poetry Magazine, argued that: "Enough Rope is what the well-dressed man or woman will wear inside their heads instead of brains. Here is poetry that is 'smart' in the fashion designer's sense of the word. Mrs. Parker need not hide her head in shame, as the average poet must, when she admits the authorship of this book." Luhrs added "in its lightness, its cynicism, its pose, she had done the right thing... it is high time that a poet with a monocle looked at the populace, instead of the populace looking at the poet through a lorgnette."

Parker was compared to Edna St. Vincent Millay. The poet, Genevieve Taggard, wrote in the New York Herald Tribune: "Mrs Parker had begun in the thoroughly familiar Millay manner and worked into something quiter her own... Miss Millay remains lyrically, of course, far superior to Mrs Parker... But there are moods when Dorothy Parker is more acceptable, whisky straight, not champagne." Alexander Woollcott complained when some reviewers described Parker's poetry as "light" and by implication to dismiss it as being inconsequential. He argued that it was "thrilling poetry of a piercing and rueful beauty".

Edmund Wilson in the New Republic argued that the best of her poems were "extraordinary vivid and possessed a frankness that justified her departure from literary convention". He pointed out that "her wit is the wit of her particular time and place" and her writing "had its roots in contemporary reality". Wilson claimed that Parker had emerged as "a distinguished and interesting poet". The poet, John C. Farrar, argued in The Bookman that Parker wrote "poetry like an angel" that she was a "giantess of American letters secure at the tope of her beanstalk". This praise helped Enough Rope to became a national best seller and ran to eight printings. This was almost an unprecedented achievement for a volume of poetry.

Bartolomeo Vanzetti and Nicola Sacco were convicted for murdering Frederick Parmenter and Alessandro Berardelli during a robbery. Many people felt that they had been wrongly convicted and her friend, Heywood Broun, became very involved in the campaign to free them. In 1927 Governor Alvan T. Fuller appointed a three-member panel of Harvard President Abbott Lawrence Lowell, the President of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Samuel W. Stratton, and the novelist, Robert Grant to conduct a complete review of the case and determine if the trials were fair. The committee reported that no new trial was called for and based on that assessment Governor Fuller refused to delay their executions or grant clemency. Walter Lippmann, who had been one of the main campaigners for Sacco and Vanzetti, argued that Governor Fuller had "sought with every conscious effort to learn the truth" and that it was time to let the matter drop.

It now became clear that Sacco and Vanzetti would be executed. Heywood Broun was furious and on 5th August he wrote in New York World: "Alvan T. Fuller never had any intention in all his investigation but to put a new and higher polish upon the proceedings. The justice of the business was not his concern. He hoped to make it respectable. He called old men from high places to stand behind his chair so that he might seem to speak with all the authority of a high priest or a Pilate. What more can these immigrants from Italy expect? It is not every prisoner who has a President of Harvard University throw on the switch for him. And Robert Grant is not only a former Judge but one of the most popular dinner guests in Boston. If this is a lynching, at least the fish peddler and his friend the factory hand may take unction to their souls that they will die at the hands of men in dinner coats or academic gowns, according to the conventionalities required by the hour of execution."

Parker was not interested in politics and had never voted in her life. However, this case had stirred her conscience and she decided to travel to Boston to take part in the demonstrations against the proposed execution of Bartolomeo Vanzetti and Nicola Sacco. Other campaigners who had arrived in the city included Ruth Hale, John Dos Passos, Susan Gaspell, Edna St. Vincent Millay, Mary Heaton Vorse, Upton Sinclair, Katherine Anne Porter, Michael Gold and Sender Garlin.

On 10th August, 1927, Parker was arrested by the police during a demonstration. She was taken to Joy Street Police Station. A crowd followed them shouting "Hang her!" "Kill her!" "Bolsheviki!" and "Red scum". Ruth Hale and Seward Collins came to bail her out. There were a crowd of reporters waiting for her outside. She responded to their questions by a series of wisecracks: "I thought prisoners who were set free got five dollars and a suit of clothes," she said to loud laughter. She told them that they had not taken her fingerprints "but they left me a few of theirs." Parker then pushed up her sleeves to show off her bruises. The following morning she was found guilty of "sauntering and loitering" and received a five-dollar fine.

This experience had a dramatic impact on Parker and she now considered herself a socialist. She claimed that from then on "my heart and soul are with the cause of socialism". Some of her friends who were members of the Algonquin Round Table such as Heywood Broun, Donald Ogden Stewart, Ruth Hale,Jane Grant, Neysa McMein, Alice Duer Miller and Robert Benchley, were active in politics, but most of them were indifferent to such issues. Parker later recalled: "Those people at the Round Table didn't know a bloody thing. They thought we were fools to go up and demonstrate for Sacco and Vanzetti." She claimed they were ignorant because "they didn't know and they just didn't think about anything but the theater."

Parker eventually became disillusioned with the Algonquin Round Table: "The only group I have ever been affiliated with is that not especially brave little band that hid its nakedness of heart and mind under the out-of-date garment of a sense of humor... I know that ridicule may be a shield, but it is not a weapon." Parker added: "At first I was in awe of them because they were being published. But then I came to realize I wasn't hearing anything very stimulating. The one man of real stature who ever went there was Heywood Broun. He and Robert Benchley were the only people who took any cognizance of the world around them. George Kaufman was a nuisance and rather disagreeable. Harold Ross, the New Yorker editor, was a complete lunatic; I suppose he was a good editor, but his ignorance was profound."

On 1st October, 1927, Parker took over the "Recent Books" column in The New Yorker, under the pseudonym "Constant Reader". John C. Farrar, argued that Parker wrote "poetry like an angel" but "criticism like a fiend". One of those who suffered from the comments of Parker was Margot Asquith, the author of Lay Sermons (1927). Parker commented that "Margot Asquith's latest book, has all the depth and glitter of a worn dime." She added that "the affair between Margot Asquith and Margot Asquith will live as one of the prettiest love stories in all literature". Parker was not always negative and praised the work of Sinclair Lewis, Ernest Hemingway, James Baldwin, Scott Fitzgerald and Edwin Albee. Her biographer, John Keats, has argued: "Her taste was most uneven, but her writing was consistent. It was consistently awkward whenever she sought to praise a book, and consistently vivid and crisp when she did not, as was more often the case."

Seward Collins had become the owner and the editor of The Bookman. In February 1929, Collins published Parker's Big Blonde. The critic, Franklin Pierce Adams, commented that it was the "best short story I have read in so long a time that I cannot say". Later that year it was awarded the O. Henry Prize.Another supporter of Parker was Edmund Wilson. He argued: "She is not Emily Bronte or Jane Austen, but she has been at some pains to write well, and she has put into what she has written a voice, a state of mind, an era, a few moments of human experience that nobody else has conveyed."

Somerset Maugham was another writer who appreciated Parker's work: “She had a wonderfully delicate ear for human speech and with a few words of dialogue, chosen you might think haphazardly, will give you a character complete in all its improbable plausibility. Her style is easy without being slipshod and cultivated without affection. It is a perfect instrument for the display of her many-sided humour, her irony, her sarcasm, her tenderness, her pathos.” Vincent Sheean pointed out: "There was a great element of suppressed fury in Dottie... She was a terrified woman and a terrified artist. She was a true artist. Among contemporary artists, I would put her next to Hemingway and Bill Faulkner... Every word had to be true, this is terrifying. That's what Dottie had; every word had to be true."

Parker began to drink heavily. A friend, Diana Forbes-Robinson, claimed that: "She gave off an aura of troubledness. I think she drank because of her perception. She wanted to dull her perceptions. Her vision of life was almost more than she could bear... Was she suffering from being so damned clever? I do believe that Dottie was infinitely superior to her surroundings - she had some inner ear that the others didn't have... I wonder if that extremely apologetic way of hers wasn't a supreme effort to hide the contempt she may have felt. The politer her language, the more lethal was what was going to come out next. I am sure there was a core in Dottie that was tough as nails. She would do what she wanted regardless of anyone else."

John Keats, the author of You Might as Well Live: The Life and Times of Dorothy Parker (1971) has pointed out: "As is the case with many a literary artist, as distinguished from the professional writer who can always go to his typewriter and get work done, writing did not come easily to Dorothy Parker. She might be lightning fast in conversation, but when she sat at her typewriter she would, as she said, write five words and erase seven. She could, and did, spend as long as six months on a single short story. She was not lazy; she was a perfectionist. Her critical sense consistently informed her that her work was not as good as it ought to be. She was frequently so depressed by being unable to create something that could stand the test of her pitiless critical judgement that there ensued periods when the towel would remain over the typewriter for weeks at a time. She suffered periodically from writer's block - a state of despair that stultifies creativity."

Parker also published two collections of short stories: Laments for the Living (1930) and After Such Pleasure (1931). Franklin Pierce Adams wrote in the New York Herald-Tribune: "More certain than either death or taxes is the high and shining art of Dorothy Parker... Bitterness, humour, wit, yearning for beauty and love, and a foreknowledge of their futility - with rue her heart is laden, but her lads are gold-plated - these, you might say, are the elements of the Parkerian formula; these, and the divine talent to find the right word and reject the wrong one. The result is a simplicity that almost startles."

Mark Van Doren compared her work to that of Ring Lardner: "Mrs Parker has listened to her contemporaries with as sharp a pair of eyes as anyone has had in the present century, unless, to be sure, Lardner is to be considered, as he probably is, without a rival in his field. Mrs Parker is more limited than Lardner; she is expert only with sophisticates... But she does her lesser job quite perfectly, achieving as she does it a tone half-way between sympathy and satire... Again it is only Ring Lardner who can be compared with her in the matter of hatred for stupidity, cruelty, and weakness."

In 1932 met the actor and writer, Alan Campbell. The previous year he had been given a three-month contract with Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. Campbell later recalled: "After some weeks, I ran away. I could not stand it anymore. I just sat in a cell-like office and did nothing. The life was expensive and the thousands of people I met were impossible. They never seemed to behave naturally, as if all their money gave them a wonderful background they could never stop to marvel over. I would imagine the Klondike like that - a place where people rush for gold." However, Campbell was convinced that with the right partner he could make it as a script-writer.

According to Marion Meade, the author of Dorothy Parker: What Fresh Hell is This? (1989): "She (Parker) was immediately impressed by Alan's golden good looks, the fine bone structure, the fair hair and dazzling smile that made it seem as if he had just stepped indoors on a June day. He resembled Scott Fitzgerald when Scott had been young and healthy, before he began drinking heavily, and some people thought him far better looking. Alan, like Scott, had a face that was a touch too pretty for a man, the kind of features that caused people to remark he would have made a splendid woman. He was typecast by producers as a classic juvenile."

Campbell later recalled: "Dottie was the only woman I ever knew whose mind was completely attuned to mine... No one in the world had made me laugh as much as Dottie." John Keats has pointed out: "They had arrived in each other's lives at the very moment each most needed the other. Alan was at a turning point. He was an unsung actor of minor roles in unimportant plays... he had faced up to the fact that his talents as an actor were meagre and that there was no real point in his continuing in a career in which he would never do particularly well."

Campbell was twenty-eight years old and Parker was thirty-nine. However, they had much to offer each other. Campbell needed a writing-partner and Parker needed someone to look after her. They rented an apartment together in New York City. According to one source: "Alan had bought the food, done the cooking, done all the interior decorating in their apartment, painted all the insides of the bureau drawers, cleaned up after the dogs, washed and dried the dishes, made the beds, told Dorothy to wear her coat on cold days, shaken the cocktails, paid the bills, amused her, adored her, made love to her, got her to cut down on her drinking, otherwise created space and time in her life for her to write."

Another friend, Donald Ogden Stewart, argued: "He (Alan Campbell) took her (Dorothy Parker) and probably kept her living. He was important in so far as taking care of her was concerned, and she was well worth taking care of. Alan was an actor, and he may have been playing a part which little by little took over, but he wasn't a villain. He kept her living and working." Ruth Goodman Goetz added: "Alan bought her clothes, fussed with her hairstyle and her perfume... Dottie was delighted to have this handsome creature around."

Parker and Alan Campbell married in 1934 in Raton, New Mexico, and moved to Hollywood. They signed ten-week contracts with Paramount Pictures, with Campbell earning $250 per week and Parker earning $1,000 per week. This would later be increased to over $2,000 a week. Their first movie scripts includedHere Is My Heart (1934) Hands Across the Table (1935), The Moon's Our Home (1936), Suzy (1936), Three Married Men (1936) and Lady Be Careful (1936).

Parker later recalled: "Through the sweat and the tears I shed over my first script, I saw a great truth - one of those eternal, universal truths that serve to make you feel much worse than you did when you started. And that is that no writer, whether he writes from love or from money, can condescend to what he writes. What makes it harder in screenwriting is the money he gets. You see, it brings out the uncomfortable little thing called conscience. You aren't writing for the love of it or the art of it or whatever; you are doing a chore assigned to you by your employer and whether or not he might fire you if you did it slackly makes no matter. You've got yourself to face, and you have to live with yourself."

Campbell liked working in Hollywood. John Keats, the author of You Might as Well Live: The Life and Times of Dorothy Parker (1971) has pointed out: "Campbell... was good at the work he was asked to do. His talents as a writer were perfectly matched to Hollywood's standards. His work was a labour of love. He loved being in Hollywood. He was thrilled to meet stars. He was a creature of the theatre and the films, and all the people who had to do with the stage and screen were at one time or another in Hollywood: he was at the centre of his world... It was not just the money, it was also the glamour and the success that he loved."

Parker and Campbell lived in a Beverly Hills mansion with a butler and a cook. They also purchased a large Colonial house in Bucks County, Pennsylvania. It was called Fox House Farm. As a result of theGreat Depression prices were low and they purchased it for $4,500, less than what the couple was being paid for a week's pay in Hollywood. Parker had also received $32,000 in royalties over a two-year period for her collected poems, Not So Deep as a Well. She wanted to start a family and became pregnant, but now aged 42, she miscarried after three months.

In 1936 Parker, Campbell and Donald Ogden Stewart met a former Berlin journalist, Otto Katz. He told them about what was happening in Nazi Germany. Stewart recalled that when Katz began to describe the rule of Adolf Hitler "the details of which he had been able to collect only through repeatedly risking his own life, I was proud to be sitting beside him, proud to be on his side in the fight." Stewart and Parker decided to join with a group of people involved in the film industry who were concerned about the growth of fascism in Europe to establish the Hollywood Anti-Nazi League (HANL). Members includedAlan Campbell, Walter Wanger, Dashiell Hammett, Cedric Belfrage, John Howard Lawson, Clifford Odets,Dudley Nichols, Frederic March, Lewis Milestone, Norma Shearer, Oscar Hammerstein II, Ernst Lubitsch,Mervyn LeRoy, Gloria Stuart, Sylvia Sidney, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Chico Marx, Benny Goodman, Fred MacMurray and Eddie Cantor. Another member, Philip Dunne, later admitted "I joined the Anti-Nazi League because I wanted to help fight the most vicious subversion of human dignity in modern history".

Parker was also a strong supporter of the Popular Front government in Spain and during then Spanish Civil War was a member of the Anti-Fascist Refugee Committee and the Motion Picture Artists Committee to Aid Republican Spain. In October 1937 Parker visited Spain and made a broadcast from Madrid Radio. She also sent back reports on the war for the the New Masses magazine. Parker also wrote an impressive short-story on the situation, Soldiers of the Republic .

Parker was attacked by the media for her anti-fascist views. An article in Life Magazine pointed out that her views were held by only a small minority of the population. It reported that popular political and religious figures such as Alfred E. Smith, Father Charles Edward Coughlin, Archbishop Michael Curleyand Hiram Wesley Evans, the Imperial Wizard of the Ku Klux Klan, fully supported the forces of GeneralFrancisco Franco.

During this period Parker described herself as a "communist". Her friends who were members of theAmerican Communist Party rejected this claim and pointed out that she also claimed that PresidentFranklin D. Roosevelt "was God". Beatrice Ames Stewart claimed that "Dorothy Parker... was not a personal friend of the multitudes... contrariness was the wellspring of her Communism. She was anti. She was anti the Establishment."

Donald Ogden Stewart argued that Parker was motivated by her hostility towards Adolf Hitler: "Dottie was ready to do anything as far as fighting Hitler went. She made speeches and collected money. The Anti-Nazi League developed into quite a concern, because we could call on stars like Norma Shearer and Freddie March, and have them make speeches, and Dottie was always good, and I think she found a lot of pleasure in doing that sort of thing. But she was also terribly sincere."

Alan Campbell became increasingly concerned about Parker's political activity. As John Keats pointed out: "He (Campbell grew more and more concerned. He told Dorothy that her politics were dangerous. Being against Hitler might be all very well, but the kind of people who were most strongly against Hitler were also on the side of the labour unions, and the studios didn't like people who were on the side of unions. Making speeches in Hollywood couldn't hurt Hitler, Alan argued, but it could very well hurt Dorothy Parker and Alan Campbell with the studios."

Parker was a generous supporter of political causes. This included donations to the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), the Abraham Lincoln Brigade that was fighting in theSpanish Civil War, the Democratic Party, the League of Women Voters and the Los Angeles Boys Athletic League. There is no evidence she gave any money to the American Communist Party. She also wrote occasional articles on injustice. For example, Scribner's Magazine published Clothe the Naked , an article about the great inequality between the races.

Hiram Beer worked as a gardener, chauffeur and carpenter at the Fox House Farm was amazed at the vast amount of alcohol the couple consumed. He said Parker drank Manhattans and Campbell, Scotch on the rocks, and when not this, they shared pitchers of Martinis: "They'd bring it in by the cases, and both of them used to run around with drinks in their hands even when there was no company there. When they had people there, they had people who felt they had to drink just because they were there, and that's what there was to do. They'd all get up past noon, and after their lunch, or breakfast as it might have been, they'd start drinking until late at night."

John Keats, has suggested that "Dorothy Parker... lived with a fretful husband in a rather oddly furnished house, quarrelling with her friends, allowing herself to grow dumpy in barren middle age, wasting her time on silly scripts, stunning herself with alcohol and sleeping pills, loving the working man in general while despising him in particular, ridiculing as meretricious the artistry that had enabled her to become the mistress of a New York apartment, a California mansion, and a country estate. Between 1935 and 1937, she spent herself as she spent her money: as if she hated both."

In 1937 Parker and Campbell were recruited to write the screenplay for A Star is Born (1937). The film was nominated for seven Academy Awards, winning the award for Best Story. Other films they worked on included Trade Winds (1938), The Cowboy and the Lady (1938), Sweethearts (1938) and Trade Winds (1938).

In August 1939, Joseph Stalin and Adolf Hitler signed the Soviet-Nazi Pact. Soon afterwards Hitler gave orders for the invasion of Poland. This forced Neville Chamberlain to declare war on Germany starting the Second World War. Three weeks later Stalin ordered the Red Army to invade Poland from the east, meeting the Germans in the centre of the country. The leaders of the American Communist Partyaccepted Stalin's message that the war was not against fascism but just another "imperialist war between capitalistic nations". Parker was appalled by these events and friends who had joined the party felt betrayed and quit the party in angry disgust seeing it as an agent of Soviet foreign policy.

Parker spent more time at her home in Bucks County and published a collection of short-stories, Here Lies (1940). The reviewer in The Spectator argued: "The urbanity of these stories is that of a worldly, witty person with a place in a complex and highly-developed society, their ruthlessness that of an expert critical intelligence, about which there is something clinical, something of the probing adroitness of a dentist: the fine-pointed instrument unerringly discovers the cautious cavity behind the smile... Mrs Parker may be amused, but it is plain that she is really horrified. Her bantering revelations are inspired by a respect for decency, and her pity and sympathy are ready when needed."

In 1937 Parker and Alan Campbell were recruited to write the screenplay for A Star is Born (1937). The film was nominated for seven Academy Awards, winning the award for Best Story. Other films they worked on included Trade Winds (1938), The Cowboy and the Lady (1938), Sweethearts (1938), Trade Winds(1938), The Little Foxes (1941), Weekend for Three (1941) and Saboteur (1942). Some people claimed that Campbell only got work because of Parker. Budd Schulberg disagreed: "Her (Parker) work habits were terrible, but Alan was extremely disciplined. He dragged her along. At United Artists, I watched how they worked... In his own right he was a really good screenwriter, maybe because he'd once been an actor, but nobody gave him credit."

Left-wing writers such as Campbell and Parker were attacked by Martin Dies, the chairman of the House of Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC). In 1940 Parker responded by arguing: "The people want democracy - real democracy, Mr. Dies, and they look toward Hollywood to give it to them because they don't get it any more in their newspapers. And that's why you're out here, Mr. Dies - that's why you want to destroy the Hollywood progressive organizations - because you've got to control this medium if you want to bring fascism to this country." It was pointed out that people like Campbell and Parker were guilty of being a "premature anti-Fascists".

During the Second World War Campbell volunteered to join the United States Army Air Forces. In 1942 he was sent to the Air Force ground school at Miami Beach where he served with Joshua Logan, theBroadway director. Parker visited Campbell as often as she could. Nedda Harrigan, Logan's future wife, commented that she was with them at a party on the base: "They were terribly intimate, only if wasn't cozy or jolly, more like a couple of vipers. Of course we were all drinking heavily, because that was standard procedure in the air force, but she was in a bad temper and later on they had a terrible fistfight." Harrigan urged Parker not to take the quarrel seriously as war was difficult and they were all in the "same boat". Parker disagreed, replying, "my boat is leaking".

In 1943 Parker applied to join the Women's Army Corps but was rejected as she had passed her fiftieth birthday. Parker hated being middle-aged and wanted to skip her fifties and get to the seventies and eighties. "People ought to be one of two things, young or old. No; what's the good of fooling? People ought to one of two things, young or dead." Parker also became depressed by the early deaths of close friends, Alexander Woollcott, Heywood Broun and Robert Benchley.

Parker applied to become a foreign correspondent. She was once again rejected, this time because the government was unwilling to grant passports to people with well-known left-wing views. She therefore followed Campbell from camp to camp. In the summer of 1943 Campbell was based in Northampton,Hampshire County, and Parker stayed as a house-guest with one of his fellow officers, Robeson Bailey. His wife said: "She was self-effacing; she was quiet. I wanted to protect her. She was so damned decent, and yet she had this legend of indecency about her, encrusted with the New York glamour... They seemed to be just a very happily married couple despite the disparity in age. He obviously must have had a mother thing about her, I should think." In 1944 Campbell was sent to London where he served as an officer in Army Intelligence.

In July 1944 Parker wrote an article for Vogue Magazine about what it was like to be the wife of a soldier serving overseas. This was based partly on her experiences of her first husband, Edwin Pond Parker in the First World War: "You say goodnight to your friends, and know that tomorrow you will meet them again, sound and safe as you will be. It is not like that where your husband is. There are the comrades, closer in friendship to him than you can ever be, whom he has seen comic or wild or thoughtful; and then broken or dead. There are some who have gone out with a wave of the hand and a gay obscenity, and have never come back. We do not know such things; prefer, and wisely, to close our minds against them... I have been trying to say that women have the easier part in war. But when the war is over - then we must take up. The truth is that women's work begins when war ends, begins on the day their men come home to them. For who is that man, who will come back to you? You know him as he was; you have only to close your eyes to see him sharp and clear. You can hear his voice whenever there is silence. But what will he be, this stranger who comes back? How are you to throw a bridge across the gap that has separated you - and that is not the little gap of months and miles? He has seen the world aflame; he comes back to your new red dress. He has known glory and horror and filth and dignity; he will listen to you tell of the success of the canteen dance, the upholsterer who disappointed, the arthritis of your aunt. What have you to offer this man? There have been people you never knew with whom he has had jokes you could not comprehend and talks that would be foreign to your ear. There are pictures hanging in his memory that he can never show to you. Of this great part of his life, you have no share... things forever out of your reach, far too many and too big for jealousy. That is where you start, and from there you go on to make a friend out of that stranger from across a world."

In 1947 Parker became involved with Ross Evans, a young actor and writer. Beatrice Ames Stewart said that he was "a beautiful hunk" who looked like Victor Mature. A woman at a party complimented him on his wonderful sun tan. Parker said he had the "hue of availability". Later that year she divorced Alan Campbell. When her friend, Vincent Sheean, said he felt sorry for Campbell she commented: "Oh, don't worry about Alan. He will always land on somebody's feet."

Dorothy Parker wrote the screenplays for two more films, A Woman Destroyed (1947) and Lady Windermere's Fan (1949). She also wrote a play with Ross Evans entitled The Coast of Illyria that was based on the life of Charles Lamb. It opened in Dallas in the spring of 1949. It received reasonable reviews but it was not transferred to Broadway. It was performed in London and at the Edinburgh Festival but it was not a success. Its failure was one of the reasons why Evans left Parker. According to Parker another reason was that Evans discovered she was "half a Jew".

Parker now contacted Campbell who had found it difficult to find work since their divorce. He agreed to remarry her. Parker told her friends: "I've been given a second chance. I've been given a second chance - and who in life gets a second chance?" Another friend said: "He (Alan) was marrying her because he wanted to help take care of her. Alan was so wonderful for her, and she would crucify him, but she relied on him and he was lovely to her." Their second marriage took place on 17th August, 1950.

In June, 1950, three former FBI agents and a right-wing television producer, Vincent Harnett, publishedRed Channels, a pamphlet listing the names of 151 writers, directors and performers who they claimed had been members of subversive organisations before the Second World War. The names had been compiled from FBI files and a detailed analysis of the Daily Worker, a newspaper published by theAmerican Communist Party. The list included Parker and Campbell. A free copy was sent to those involved in employing people in the entertainment industry. All those people named in the pamphlet were blacklisted until they appeared in front of the House of Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) and convinced its members they had completely renounced their radical past. As a result both Alan Campbell and Parker were blacklisted.

John Keats has pointed out: "Alan Campbell was a victim of the Red hunt, despite his well-known objections to Dorothy Parker's pre-war political activities and his refusal to have anything to do with them. Because her career in films was over, he could not offer himself and Dorothy Parker as a writing team to any studio, nor was any studio willing to employ him alone, because he was the husband of a suspected Communist. To be unemployed in Hollywood is normally to be regarded as a pariah, but in these abnormal times it was something worse. No one knew who might be reported for his association with someone else, however slight that association might be; no one knew how suspect were the friends of his friends. There was no help for this: no one could say when, or whether, the terror would end... the House Committee on Un-American Activities said it had evidence that Dorothy Parker was a Communist. She was angrily noncommittal when questioned by newspaper reporters. She refused to become one of those who went crawling to the Committee, or to the studios, to wear the guise of a penitent and seek redemption and good fortune by being traitorous."

The couple left Hollywood and moved back to New York City. In April 1951, Parker and Campbell were visited by two FBI agents. They asked if they knew Dashiell Hammett, Lillian Hellman, Donald Ogden Stewart, Ella Winter and John Howard Lawson and if they had attended meetings of the American Communist Party with them. The agents reported: "She was a very nervous type of person... During the course of this interview, she denied ever having been affiliated with, having donated to, or being contacted by a representative of the Communist Party."

In Parker's FBI file was a letter sent by Walter Winchell to J. Edgar Hoover. It said that Winchell had been a close friend of Parker until "she became a mad fanatic of the Commy party line". Winchell asked Hoover if he knew that "Dorothy Parker, the poet and wit, who led many pro-Russian groups." As Marion Meade, the author of Dorothy Parker: What Fresh Hell is This? (1989) has pointed out: "Many friends of hers were blacklisted, denounced as traitors, subpoenaed, cited for contempt of Congress, and sentenced to prison terms... Practically all of Dorothy's friends on the board of the Joint Anti-Fascist Refugee Committee, whose national chairman she had been, went to jail after declining to turn over records to HUAC."

Parker joined forces with Arnaud d'Usseau, to write the play Ladies of the Corridor . She told Ward Morehouse, the theatre critic, that "Arnaud d'Usseau was a rigid taskmaster. He'd work at the typewriter and then get up to pace and we'd meet each other in the middle of the room... We've put our guts into this play and we have a fine producer in Wally Fried, who worries and worries and worries... and we have a wonderful cast - just plain wonderful."

The play opened in October 1953. John McClain wrote in The New York Journal American: "The fate of lonely women, living in faded luxury in side street New York hotels, had been woven by Dorothy Parker and Arnaud d'Usseau into a drama of enormous depth and emotional appeal. We see the full power of Mrs Parker's profound and incisive preoccupation with the frailties of her sex, the tragedy and desperation that assail a world of women without men. The ladies... suffer from the mutual malady of boredom: their hours are filled with the small details of destroying time. There are some who manage to escape the barrier, but there is always the suggestion that the corridor is waiting there to claim them in the end." Other reviewers were less kind and it closed after forty-five performances."

The journalist, Wyatt Emory Cooper met Parker and Campbell for the first time in 1956. "My memory is of a stark, bare, colourless, and impersonal room, with a large bone on the floor, dog toys on the gravy-coloured sofa, a dog, of course, and an agonized Alan facing a stricken-looking Dottie, who was then, as incredible as it seems to me now, actually fat. My impression was of a sad, bewildered young girl, angrily trapped inside an inappropriate and almost grotesque body. Of the desolate conversation, I remember only that she apologized repeatedly; for the disorder of the room, for her own appearance, for the behaviour of the dog, and for the absence of anything to drink... It was painful to witness the estrangement of two people who were forever to be deeply involved with each other. Loneliness and guilt were almost like physical presences in the space between them, and they spoke in short, stilted, and polite sentences with terrible silences in between, and, yet, there was a tenderness in the exchange, a grief for old hurts, and a shared reluctance to turn loose."

In 1957 Arnold Gingrich, the publisher of Esquire Magazine, agreed to pay Dorothy Parker $750 a month to review books. Harold Hayes, the editor of the magazine, later claimed that she had difficulty reaching deadlines. "She seemed sincerely to detest writing. She truly hated to write. She just lie about how far along she was with a piece. She fled from the problem of doing anything... When finally she would turn in a piece, she expressed great dismay about it. She thought there was little value in anything she had done. When I would attempt to reassure her, she would hang on to my praise with the gratefulness of a small child... She never lost her capacity as a writer. When she was able to force herself to the typewriter, she was marvellously precise and witty - her voice was as true and distinctive as in her writing in the twenties."

Alan Campbell died after taking an overdose of sleeping pills in Los Angeles on 14th June, 1963. The coroner's report showed that he had died of "acute barbiturate poisoning due to an ingestion of overdose" and listed him as a probable suicide. His friend, Nina Foch, said: "I don't think he meant to kill himself, but I also felt that he'd not unaccidently done the thing." According to John Keats: "A physician said it was not necessarily a case of suicide; it is not unusual for a drunken person, asleep under sedation by barbiturates, to strangle on his own vomit. It was decided that death had been caused by accident."

Parker's health was also poor because of her heavy drinking. However, she did occasionally review books for Esquire Magazine. Parker particularly admired James Baldwin, Truman Capote, Saul Bellow andVladimir Nabokov. She liked his most famous novel, Lolita (1958): "As this is being beaten out on the typewriter, it has not reached its publication in the United States. Lolita, as you undoubtedly know, has had an enormous share of trouble, and caused a true hell of a row. It was first published in Paris, and was promptly banned throughout France.... I do not think that Lolita is a filthy book. I cannot regard it as pornography, either sheer, unrestrained, or any other kind. It is the engrossing, anguished story of a man, a man of taste and culture, who can love only little girls."

Parker did not have many visitors in her last years. Lillian Hellman admitted that she had not seen her as much as she should: "True, I was there in emergencies, but I was out of the door immediately they were over". In her last years the only person she visited was Beatrice Ames Stewart. "I would prepare dinner for her. I was feeding her in the last year, but we never said anything about it. I gave her money to go home with every night."

Dorothy Parker died of a heart-attack, in New Jersey on 22nd August, 1967. In her will, she bequeathed her estate of $20,000 to Martin Luther King. Following King's death, her estate was passed on to the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People.

(1) Donald Ogden Stewart, quoted by John Keats, in

You Might as Well Live: The Life and

Times of Dorothy Parker (1971)

Dottie was attractive to everybody - the eyes were so wonderful, and the smile. It wasn't difficult to fall in love with her. She was always ready to do anything, to take part in any party; she was ready for fun at any time when it came up, and it came up an awful lot in those days. She was fun to dance with and she danced very well, and I just felt good when I was with her, but I think if you had been married to Dottie, you would have found out, little by little, that she really wasn't there. She was in love with you, let's say, but it was her emotion; she was not worrying about your emotion. You couldn't put your finger on her. If you ever married her, you would find out eventually. She was both wide open and the goddamnedest fortress at the same time. Every girl's got her technique and shy, demure helplessness was part of Dottie's - the innocent, bright-eyed little girl that needs a male to help her across the street. She was so full of pretence herself that she could recognize the thing. That doesn't mean she did not hate sham on a high level, but that she could recognize pretence because that was part of her make-up. She would get glimpses of herself doing things that would make her hate herself for that sort of pretence.

(2) John Keats, You Might as Well Live: The Life and Times of Dorothy Parker (1971)

As is the case with many a literary artist, as distinguished from the professional writer who can always go to his typewriter and get work done, writing did not come easily to Dorothy Parker. She might be lightning fast in conversation, but when she sat at her typewriter she would, as she said, write five words and erase seven. She could, and did, spend as long as six months on a single short story. She was not lazy; she was a perfectionist. Her critical sense consistently informed her that her work was not as good as it ought to be. She was frequently so depressed by being unable to create something that could stand the test of her pitiless critical judgement that there ensued periods when the towel would remain over the typewriter for weeks at a time. She suffered periodically from writer's block - a state of despair that stultifies creativity.

(3) Dorothy Parker, Ballade at Thirty-five (1928)

This, no song of an ingénue,This, no ballad of innocence;This, the rhyme of a lady whoFollowed ever her natural bents.This, a solo of sapience,This, a chantey of sophistry,This, the sum of experiments, -I loved them until they loved me.Decked in garments of sable hue,Daubed with ashes of myriad Lents,Wearing shower bouquets of rue,Walk I ever in penitence.Oft I roam, as my heart repents,Through God's acre of memory,Marking stones, in my reverence,"I loved them until they loved me."Pictures pass me in long review,Marching columns of dead events.I was tender, and, often, true;Ever a prey to coincidence.Always knew I the consequence;Always saw what the end would be.We're as Nature has made us - henceI loved them until they loved me.

(4) Elmer Rice, Minority Report (1964)

Dorothy Parker had written a first act which Goodman felt had great promise but lacked theatrical craftsmanship... The characters, suburbanites all, just went on talking and talking. But they were sharply realized, and the dialogue was uncannily authentic and very funny. Since I have always enjoyed the technical side of playwriting, I agreed to Goodman's proposal; not without some misgiving, however, for, though I had never met Dorothy, I had heard tales about her temperament and undependability.

(5) Dorothy Parker, broadcast, Madrid Radio (October 1937)

I came to Spain without my axe to grind. I didn't bring messages from anybody, nor greetings to anybody. I am not a member of any political party. The only group I have ever been affiliated with is that not especially brave little band that hid its nakedness of heart and mind under the out of date garment of a sense of humour. I heard someone say, and so I said it too, that ridicule is the most effective weapon. I don't suppose I ever really believed it, but it was easy and comforting, and so I said it. Well, now I know that there are things that have never really been funny, and never will be. And I know that ridicule may be a shield, but it is not a weapon.In spite of all the evacuation, there are still nearly a million people here in Madrid. Some of them - you may be like that yourself - won't leave their homes and their possessions, all the things they have gathered together through the years. They are not at all dramatic about it. It is simply that anything else than the life they have made for themselves is inconceivable to them. Yesterday I saw a woman who lives in the poorest quarter of Madrid. It has been bombarded twice by the fascists; her house is one of the few left standing. She has seven children. It has been suggested to her that she and the children leave Madrid for a safer place. She dismisses such ideas easily and firmly.Every six weeks, she says, her husband has 48 hours leave from the front. Naturally he wants to come home to see her and the children. She, and each one of the seven, are calm and strong and smiling. It is a typical Madrid family.Six years ago, when the Royal romp, Alfonso, left his racing cars and his racing stables and also left, by popular request, his country, there remained 28 million people. Of them, 12 million were completely illiterate. It is said that Alfonso himself had been taught to read and write, but he had not bothered to bend the accomplishments to the reading of statistics nor the signing of appropriations for schools.Six years ago, almost half the population of this country was illiterate. The first thing that the Republican government did was to recognise this hunger, the starvation of the people for education. Now there are schools even in the tiniest, poorest, villages; more schools in a year than ever were in all the years of the reigning kings. And still more are established every day. I have seen a city bombed by night, and the next morning the people rose and went on with the completion of their schools. Here in Madrid, as well as in Valencia, a workers' institute is open. It is a college, but not a college where rich young men go to make friends with other rich young men who may be valuable to them in business with them later. It is a college where workers, forced to start as children in fields and factories, may study to be teachers or doctors or lawyers or scientists, according to their gifts. Their intensive university course takes two years. And while they are studying, the government pays their families the money they would have been earning.In the schools for young children, there is none of the dread thing you have heard so much about - depersonalisation. Each child has, at the government's expense, an education as modern and personal as a privileged American school child has at an accredited progressive school. What the Spanish government has done for education would be a magnificent achievement, even in days of peace, when money is easy and supplies are endless. But these people are doing it under fire.

(6) Dorothy Parker, The Heart of Spain (1952)

I stayed in Valencia and in Madrid, places I had not been since that fool of a king lounged on the throne, and in those two cities and in the country around and between them, I met the best people anyone ever knew. I had never seen such people before. But I shall see their like again. And so shall all of us. If I did not believe that, I think I should stand up in front of my mirror and take a long, deep, swinging slash at my throat.For what they stood for, what they have given others to take and hold and carry along - that does not vanish from the earth. This is not a matter of wishing or feeling; it is knowing. It is knowing that nothing devised by fat, rich, frightened men can ever stamp out truth and courage, and determination for a decent life.It is impossible not to feel sad for what happened to the Loyalists in Spain; heaven grant we will never not be sad at stupidity and greed. To be sorry for those people - no. It is a shameful, strutting impudence to be sorry for the noble. But there is no shame to honorable anger, the anger that comes and stays against those who saw and would not aid, those who looked and shrugged and turned away.

(7) Dorothy Parker on working as a screenwriter in Hollywood.

When I dwelt in the East I had my opinion of writing for the screen. I regarded it with a sort of benevolent contempt, as one looks at the raggedy printing of a backward six-year-old. I thought it had just that much relationship to literature.Well, I found out, and I found out hard, and found out forever. Through the sweat and the tears I shed over my first script, I saw a great truth - one of those eternal, universal truths that serve to make you feel much worse than you did when you started. And that is that no writer, whether he writes from love or from money, can condescend to what he writes. What makes it harder in screenwriting is the money he gets.You see, it brings out the uncomfortable little thing called conscience. You aren't writing for the love of it or the art of it or whatever; you are doing a chore assigned to you by your employer and whether or not he might fire you if you did it slackly makes no matter. you've got yourself to face, and you have to live with yourself.

(8) Dorothy Parker made an attack on Martin Dies and his

Un-American Activities Committee in the magazine

Directions (April, 1940)

The people want democracy - real democracy, Mr. Dies, and they look toward Hollywood to give it to them because they don't get it any more in their newspapers. And that's why you're out here, Mr. Dies - that's why you want to destroy the Hollywood progressive organizations - because you've got to control this medium if you want to bring fascism to this country.

(9) Dorothy Parker, Vogue Magazine (July, 1944)

You say goodnight to your friends, and know that tomorrow you will meet them again, sound and safe as you will be. It is not like that where your husband is. There are the comrades, closer in friendship to him than you can ever be, whom he has seen comic or wild or thoughtful; and then broken or dead. There are some who have gone out with a wave of the hand and a gay obscenity, and have never come back. We do not know such things; prefer, and wisely, to close our minds against them ...I have been trying to say that women have the easier part in war. But when the war is over - then we must take up. The truth is that women's work begins when war ends, begins on the day their men come home to them. For who is that man, who will come back to you? You know him as he was; you have only to close your eyes to see him sharp and clear. You can hear his voice whenever there is silence. But what will he be, this stranger who comes back? How are you to throw a bridge across the gap that has separated you - and that is not the little gap of months and miles? He has seen the world aflame; he comes back to your new red dress. He has known glory and horror and filth and dignity; he will listen to you tell of the success of the canteen dance, the upholsterer who disappointed, the arthritis of your aunt. What have you to offer this man? There have been people you never knew with whom he has had jokes you could not comprehend and talks that would be foreign to your ear. There are pictures hanging in his memory that he can never show to you. Of this great part of his life, you have no share... things forever out of your reach, far too many and too big for jealousy. That is where you start, and from there you go on to make a friend out of that stranger from across a world.

(10) Alden Whitman, The New York Times (8th June 1967)

Dorothy Parker, the sardonic humorist who purveyed her wit in conversation, short stories, verse and criticism, died of a heart attack yesterday in her suite at the Volney Hotel, 23 East 74th Street. She was 73 years old and had been in frail health in recent years.In print and in person, Miss Parker sparkled with a word or a phrase, for she honed her humor to its most economical size. Her rapier wit, much of it spontaneous, gained its early renown for her membership in the Algonquin Round Table, an informal luncheon club at the Algonquin Hotel in the nineteen-twenties.

Complete Stories

by Dorothy Parker

- Such a pretty little picture

- Too bad

- Mr. Durant

- A certain lady

- The wonderful old gentleman

- Dialogue at three in the morning

- The last tea

- Oh! He's charming! --Travelogue

- Little Curtis

- The sexes

- Arrangement in black and white

- A telephone call